From the moment I first came to Cremona in the mid-90s I have always found Gio Batta Morassi an impressive character. This was partly due to the reverence with which he was held in Cremona as a founding father of and one of the biggest names in 20th-century Italian violin making, but mainly because of his seemingly endless lively involvement with whatever was happening at the time. I used to pop in to spend a negligible amount on some unflamed maple every so often for bow wedges. He was always available to find it for me and despite my conviction that he must be frustrated by the interruption to his work, all appearances were to the contrary.

Our latest meeting was no exception. A rather irate violin maker was looking for a piece of wood for his latest project with a breathtaking lack of reverence for a man of Morassi’s age and experience. As far as this customer was concerned, Morassi was nothing more than the boss man at the local timber yard. Morassi calmly insisted that there was no maple of the desired length in stock. A seemingly endless barrage of accusations and insults did nothing to diminish the twinkle in his eye as he waited for the man’s angry spleen to vent itself at his expense. In due course it did and, impressed and bemused at the nonchalance of the man, I sat down to interview him. The result is recorded below in Morassi’s own words.

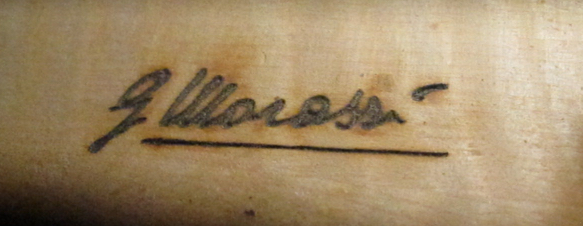

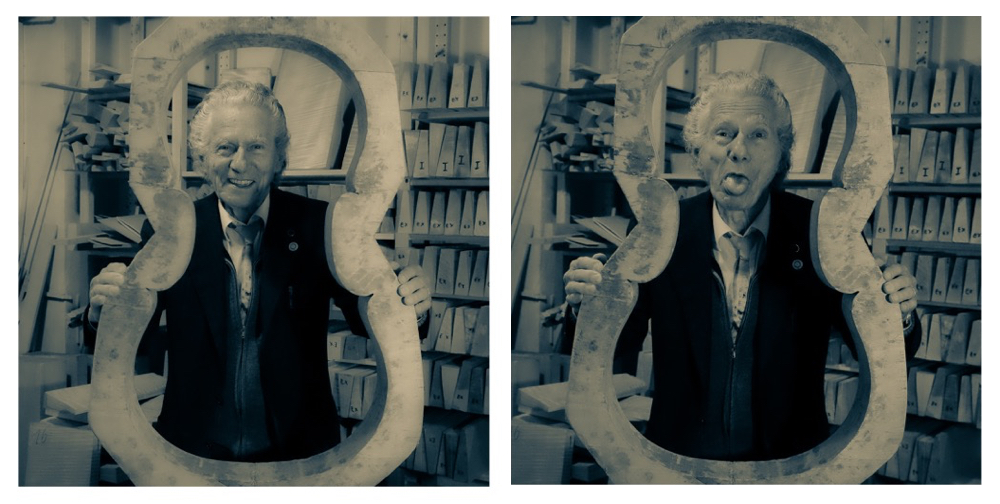

Morassi – the violin maker with a twinkle in his eye. Photos: Paul Sadka

I began studying violin making in 1950 – I come from Tarvisio in Friuli, in the mountains. At that time no one there knew what lutherie was. I said I was going to study lutherie and people said, ‘What’s that?’ I went to my local school and the Udine Chamber of Commerce was offering a bursary to a young talented student to go and study in Cremona for free – four years, with everything included, food, board, travel.

In the area where I grew up, all the wealth came from the forest, the timber. Everyone was a wood-worker. I worked with my parents in the fields and a little in the woods. I used to make the fences for animal pens. Had I not won the bursary I would have ended up as a wood dealer and be living there now.

There were five of us children (two boys and three girls), two parents and three grandparents – that’s ten in the family and only my father was working. It was pretty wretched because there just wasn’t much money. However, my childhood was beautiful – we went to school, and in our few hours of free time in the winter, those short, foggy days, we all went skiing. I went to school on skis in the winter and by bike in the summer. I had a bike that I’d repaired myself, all held together with wire.

In our few hours of free time in the winter, those short, foggy days, we all went skiing. I went to school on skis in the winter and by bike in the summer

Something that I found very satisfying was the hunting. There was plenty of game in the area – chamois, deer, foxes, martens, hares. In the winter I set traps, and we ate what we caught. Even the foxes – they don’t taste that good, but hares are good, martens really good. And there were loads of squirrels and dormice. We sold the skins of the foxes and martens. It was easy to sell them and it was very satisfying. I was always on my skis because it was impossible to go by foot as there were metres of snow. I went all over the forest and I began to understand how violins came to be made in Cremona, because the trees in this forest were the ‘Abete di Risonanza’ (the best tonewood) for violins.

During the Second World War the SS had a barracks next to us. It was a very difficult time. Every evening they were shooting with mortars and machine guns and we had to go down and lock ourselves in the cellar. So many bombings, every day! Because this was where the Germans could get through the mountains on their way to Germany. They bombed our zone terribly because there was a depot of military vehicles belonging to the Austrian army there. Our house wasn’t hit, but bombs fell close by. And the wagons went by with the Jews inside – of course, being children, we didn’t have direct contact because our parents didn’t want to tell us about it.

One day we were working in the fields and we heard two shots – pam, pam. This SS officer, so pretentious and pompous, turned up and asked, ‘Who was shooting?’ My father said that we didn’t know and that we were just working. ‘No it was you,’ the officer said. Very luckily while they were putting the handcuffs on to take him away there were another two shots, so they understood that it wasn’t my father and they left. He’d have been shot without a trial if it wasn’t for that.

There are things I’ll remember for ever. They used to bring cattle from Hungary through our station on the goods trains and they’d let the cows out to graze. So I made a deal with the Germans, we’d get a cow, kill it and eat it. And we did just that. The only problem was that the two Germans who’d come to eat at our house had stomach problems afterwards – looks like they’d eaten too much. (It was my idea!)

When I arrived by train in Cremona in 1950 I asked for the International School of Violin Making. ‘What’s that?’ they replied. But it existed – a single room in a school. The teacher Pietro Tatar was good at jewellery boxes and inlay but there was nothing there.

I got used to Cremona and began to understand how things worked. I went to Milan, to the Bisiach workshop and to see Ornati and Garimberti. They took a liking to me – I was able and passionate – and they taught me a lot, very generously. And later they also came to the Cremona school to teach once or twice a week.

I was great friends with Renato Scrollavezza, and we were always arm-wrestling. He’d already had some instrument making experience before joining the school, he’d made a few guitars and violins, but with no help – it was entirely his own personal stuff. He set the ribs into a channel in the back on his first instruments, as some old makers used to do. But he stopped all that after being at the school.

I used to tease Garimberti – for example I asked him how to put the varnish on, what brush you use, is it true you turn the brush round and use the handle end?

[Ferdinando] Garimberti was a really nice person, but I noticed he didn’t want to teach me too much. I used to tease him with this – for example I asked him how to put the varnish on, what brush do you use, is it true you turn the brush round and use the handle end? He was in charge of the exhibition of Stradivari violins in Isola Bella on Lago Maggiore [in 1963]. There were loads of violins on display, and he said to me, ‘When it’s closed we’ll go in and hold these Stradivaris in our hands.’ He explained things to me and took me to see instruments in Florence and other collections of interesting instruments. He used to ride on the back of my motorbike – I would accelerate hard and then brake just to get him going.

Pietro Sgarabotto was different, much more serious, and he wasn’t much good at violin making. His father was very good but he didn’t ever teach. Pietro used to puff himself up and was very proud of himself. He used to say ‘after Stradivari my father was born’. I teased him because he had a real bee in his bonnet for the internal form, head over heels in love with it. He used to say that a violin made with the external form won’t sound good – the usual rubbish. He hated it but I learnt to use the external form from Garimberti and Ornati. It’s very similar to the French one but it isn’t the French one.

Morassi in his Cremona workshop. Photo: Paul Sadka

There’s no difference between the internal and the external form, none! I’ve made loads of instruments from both forms but no one can tell the difference. You can’t tell my work from the form but from the character. There are French violins made with the external form that are very beautiful, and there are Italian ones made with the internal form that are very ugly.

Without doubt the hardest part of violin making is the varnish. I found it really hard because at that time the ingredients you could buy weren’t genuine or natural, there were many fake resins and other varnish components weren’t what they said they were. They used to sell brick dust as dragon’s blood! Obviously you’re really going to struggle with artificial products.

The most satisfying part for me at the time was selling a violin. It was really difficult because there was an absolute division – new instruments were for beginners and old instruments were for serious musicians, whether student or master. My first sale was to Max Möller of Amsterdam.

Giovanni Battista Morassi went on to win many prizes for his instruments, including ten gold medals, and became a teacher at the Cremona Violin Making School in 1959. He retired from the school in 1983. He died in February 2018, a little over a year after this interview was published. Read the tribute by his former student, Zheng Quan.

Paul Sadka is an award-winning bow maker currently working in France. He first met Morassi when living in Cremona in the 1990s.