It was a grey afternoon on which I made my way from Cremona to San Damaso, five miles south of Modena, where the violin maker Giancarlo Guicciardi, the most significant pupil of Ansaldo Poggi, lives and works. Despite some recent storm damage to their home, Guicciardi had agreed to give me an interview. His daughter Raffaella, a partner in the business since 1989, was also there and from time to time was able to facilitate the communication between us or elaborate on something her father had said.

During the war we were actually living on the front line [in Spilamberto] and we had Germans living in our house. They’d requisitioned it so we were billeted out and we had to live with my maternal grandfather. My grandparents were peasants and in the fields belonging to us there was a camp where German soldiers were based. I remember everything – how we had to give up our house, stable and barn, and the soldiers’ black horses, which seemed enormous to me as I was so little. I remember the hunger and the poverty.

We were only 3 km from an enormous powder factory where they made explosives. The allies tried to bomb this depot. They never managed it, but they bombed all around it. Often when we went through the fields the Allied machine guns fired at us. They knew there was a German camp in the vicinity, saw figures in the grass and so simply shot on sight. What a relief when the war was over! The fields around us were filled with craters and even now we come across them.

Giancarlo Guicciardi in his workshop

After the war it wasn’t much better. I had a brother and sister and my mother had to go and work at this gunpowder factory. I was already at work when I was eight. From 8am to 12.30pm I went to school, then after lunch I went to work in the furniture making workshop. After middle school I went to work in a large carpentry and after that I was the fire man operating the boiler at the distillery. My religious instructor, a priest, had noticed that I was being worked too hard and found me this job. The work was less intense but it meant I could bring home a wage nevertheless.

A crucial moment for me was when I was 20 years old and for the first time we had a television in the house. We were watching the New Year’s concert from Vienna and I was very impressed and I announced that I wanted to make violins! I began to gather all the equipment I needed and in due course I managed it. Then I worked during the day to earn my living, and at night I worked to get some instruments made. I worked for 16 hours a day for 20 years! One day in 1963 it was suggested to me by Vincenzo Cavani and Cesare Tacconi (an antiques dealer in Spilamberto who was a dear friend of mine) that I should meet Ansaldo Poggi, as I wasn’t happy just visiting the Cavani workshop in Spilamberto occasionally on Saturday afternoons.

Ansaldo Poggi (left) with Giancarlo Guicciardi in 1978

Poggi was very surly. He had his friendly moments but on the whole he was a curmudgeon, critical of everything around him. He saw my work and said, ‘Carry on and I’ll see you in a few months’ – this went on until about 1965, when he showed me a Pietro Borghi violin. He said, ‘Have a good look, go home and when you come back bring me a copy of this instrument with you.’ I had a good look, went home and after a few months came back with the instrument. When he saw it he was pretty shocked. ‘Keep going, carry on,’ he said. Finally in 1967 he said, ‘You can’t go on working 18–20 hours a day. You need to leave your day job and start working seriously as a violin maker. If you’re prepared to do that I’ll accept you as a pupil.’ And so at that point things changed completely for me and in effect I began to work for him.

Poggi would give me something to do, and I’d try to do it as quickly as possible and present it to him. He wouldn’t say anything. Instead he would call his wife, Angelina, and say, ‘Look what Signor Guicciardi’s done this time.’ (He always used the formal form of address when speaking to me, and I always called him Maestro.) She would then say to me, ‘It’s fine, but take it easy, take it easy.’ I didn’t understand, but one day she told me explicitly what she meant by it: ‘Don’t be too much in a hurry because my husband will take it badly.’ He was more than 70 years old and to see things done so quickly left him feeling bad. In 1969 he had a serious heart attack and when he came out of the clinic his right hand never stopped shaking. He couldn’t do the delicate operations like purfling, f-holes and scroll finishing anymore and so I did those for him.

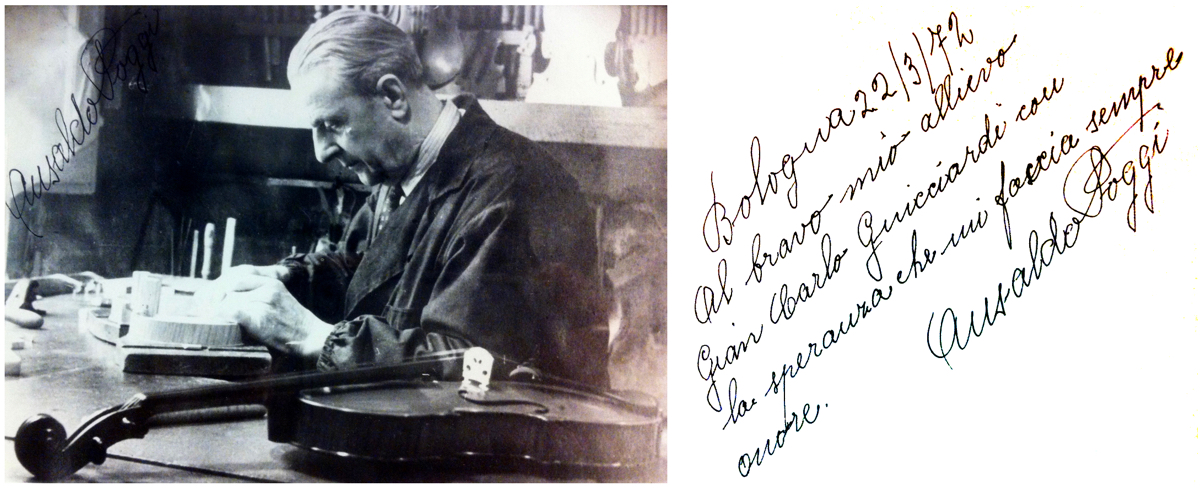

Photo of Poggi in his workshop (left), bearing a dedication to Guicciardi on the back (right)

The Poggis were generous towards me initially. They wanted to adopt me [the Italian custom of ‘giving someone your name’], because they knew that my father died when I was 18 months old. His own maestro, Giuseppe Fiorini, had asked him to take his name, but Poggi replied that he couldn’t because he already had a father and a mother. It was Signora Poggi who put the question to me one Saturday. ‘We have been thinking, me and Ansaldo,’ she said, ‘that we would like you to become our son.’ And I said, ‘Madam, let me explain a couple of things to you. I don’t want to cause my mother any offence, not with all the sacrifices she made to bring us up, so I feel unable to say that this is good for me. I can’t tell my mother that from now on I want to call myself Poggi.’ In that instant Poggi opened the door, and when he caught my eye he realised that his wife had already told me everything. They then went to the kitchen for a moment, and Signora Poggi informed him of my response. He came back saying, ‘I understand, I understand, let’s leave things how they are and carry on.’

Once Signora Poggi died in 1975 things began to change. She had had Parkinson’s for some time and there was a nurse who came to look after them both. His wife said to Poggi, ‘If I should die before you, you won’t be able to manage alone. You’re a good violin maker but at home you’re a disaster.’ So she spoke with Tina – the nurse – and after her death Tina continued to come often to the Poggi house. Some time later she became his second wife. He had always told me that he would marry twice and be widowed twice, and he was spot on.

Giancarlo Giucciardi in 1980, around the time that his collaboration with Poggi ended abruptly

In the summer months Poggi used to go up to a little villa up at Cereglio in the hills, 60 km outside Bologna. It was June 1980, and he said, ‘Don’t bother to come up this summer because I’ve got company now.’ What’s more his second wife had a son who was a psychology professor. So he brought me the last sound box [the violin body in the white] to be finished, as I’d been doing for him since 1969 – and after that I know very little about him. Our collaboration ended with no explanation from his side. It was actually through a client that I found out that he had died; I wasn’t informed by the family. I went to the funeral, but I’ve never seen anything so sad and squalid in all my days. No violin makers, nobody, and there were only 14 people present.

Poggi had been dead a while when the son came to see me. He brought with him a ring of Poggi’s, his apron and a suitcase with wood inside to make five violins with, wood that I’d given him. It was from the collection of beautiful wood that I’d originally bought from Sacconi’s widow. Mrs Sacconi had first offered it to Poggi, but Poggi said, ‘What’s the point in me, an 80-year-old man, spending so much money on wood? Ask Guicciardi. If he’s crazy enough to buy it then that’s his business.’ I was certainly stupid enough to buy it! I got a loan and I bought it. So Poggi and I arrived at the airport customs of Bologna to sign it into the country and there was this box, one cubic metre. When we saw what was in it he almost fainted. And Poggi said to me, ‘Just remember that if I ever need something nice to make a nice violin with then you’ll have to give me some.’ In fact from that moment on to the end of his life he only made violins with my wood paid for by me.

Poggi’s violins and mine differ in that mine are more highly arched – 14.5–16 mm for Poggi whereas mine reach 17–17.5 mm at times. You can see the difference between my work and Poggi’s in certain small details, even though the school is certainly the same. I always stuck to the basics that he taught me, but I’ve brought my own way of seeing, doing and feeling to the process. Because all of us have different ways of doing things. So even though I’ve respected the traditions of the school, I’ve tried to make my own improvements. If you see a scroll made by me and one by Poggi you’ll see some differences even though the school is the same.

Poggi tested several different Guarneri models until he found his ideal one. Then later he fixed on two, let’s call them Stradivari models, one small and one larger, which he in fact he called ‘my little one’ and ‘my big one’. And for his whole life he produced essentially these two Strad models and one Guarneri. I have produced fewer instruments than he did, but I have 13 models for violin, eight for viola and two for cello. I have my personal models but I’ve always been inspired by Stradivari. If I’m ever inspired by Guarneri then it’s only by his nice instruments, not those lopsided ones; I don’t like asymmetry. I’d say I’ve made roughly four Strad models to every one Guarneri model.

‘If I’m ever inspired by Guarneri then it’s only by his nice instruments, not those lopsided ones. I don’t like asymmetry’

My internal forms are expandable, not fixed at a certain length. This means I can make several model variations with one model. It’s not a secret, but who else works like that? I can put the linings on both the table side and the back side. If I used a fixed-length form I would have to break the blocks to get the form out. But I can just reduce the form size to the minimum and then I can get my form out. This way produces great symmetry between the back and the table – they’re almost identical.

Giancarlo Guicciardi at work on a violin head

I began making violins using the external form but later on Poggi forbade me to use it, calling it the French way. ‘No, Signor Guicciardi, we’ll be working the Cremonese way.’ All this internal form stuff which Sacconi and Bissolotti were so insistent on, came to them via the Giuseppe Fiorini stuff that’s now in the museum in Cremona. It’s Fiorini who perpetuated (through the so-called Strad relics) the Stradivarian, or classic Cremonese way of working. And after that it continued through Poggi. In a way even Sacconi worked with Fiorini when Fiorini was in Rome – he was never considered a pupil by Fiorini, but he was a good copyist and he even made Fiorini copies. I’ve seen 1914 Sacconi instruments which were copies of his teacher’s work, and when you saw it you’d say it was a Rossi.

The most important thing that Poggi gave me was the acoustic understanding of the violin. It takes a long time to make a violin from an acoustic point of view – you can’t make a violin in a month if you’re going to work on the acoustic side of things. I often speak with people who don’t know about applying the laws of acoustics to violin making.

Poggi produced many more instruments than I have and he didn’t do much restoration. I have done a lot of restoration in my lifetime – more than 4,000 instruments. That’s why this is only my 150th violin. I’ve made 35 violas and 15 cellos and that’s what I’ve produced up till now. My time with Poggi was difficult, but in spite of everything, I can only be grateful to my master. Without him, I wouldn’t be who I am today.

With thanks to Raffaella Guicciardi for supplying images.

Paul Sadka is an award-winning bow maker currently working in France.

Further reading: Dmitry Gindin and Roberto Regazzi explore the life of Ansaldo Poggi himself.