No man is an island,” wrote the poet John Donne in 1624, and he was right: Unquestionably, our daily interactions shape us, often more than we realize. For this reason, over a decade ago, I set out to find out more about Stradivari’s family, patrons, friends, and rivals.

An important role in Stradivari’s universe was played by his second wife, Antonia Maria Zambelli. The couple married in August 1699, just 15 months after the death of Stradivari’s first wife, Francesca Ferraboschi (1640-1698), and right before the beginning of his so-called “Golden Period”.

In this house, Antonio Stradivari and Antonia Maria Zambelli lived together for 38 years.

“Casa di A. Stradivari – Facciata,” photo by Ernesto Fazioli. Fondo EPT, 2° versamento, new numbering 1273. Archivio di Stato, Cremona. (Montage: Axel Schwalm)

Antonio Stradivari and Antonia Maria Zambelli lived together for almost forty years in the “Casa Picenardi,” which Antonio had bought in 1680. They conceived five children there, including Giovanni Battista Martino (1703-1727), who most likely assisted his father in the workshop, and Paolo Bartolomeo (1708-1775), to whom we owe the preservation of many molds, drawings, and tools from Antonio’s workshop.

What we thought we knew about Antonia Maria Zambelli, but we actually didn’t

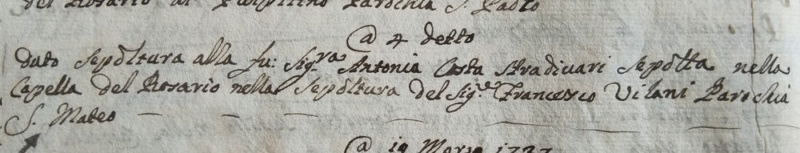

Before I began researching Antonio’s second wife, three pieces of misinformation continued to circulate in the violin world about her: that she was born on June 11, 1664; that before her marriage she ran a store with her brothers in the center of Cremona; and that her death certificate registered her as “Antonia Costa Stradivari” instead of “Antonia Zambelli Stradivari” because the priest had made a mistake.

Today we know that all of these are wrong, and here is why.

Antonia Maria’s death certificate, in which she was called “Costa” instead of “Zambelli”. Register of deaths of S. Domenico IV-1, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. Approval no. 1664/BCE/E/2023. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

Hunting for clues

I was first puzzled by Antonia Maria Zambelli’s death certificate, because it seemed highly unlikely that the priest did not know the name of Stradivari’s wife. Not only was Stradivari one of S. Matteo’s most famous parishioners, but he and his wife had lived in the parish for decades and took part in church life. How could he have forgotten her name?

I had a theory that the surname “Costa” would be found in Antonia Maria Zambelli’s past, which is why I carefully examined Cremona’s Status animarum. What are these? The Status animarum — or State of Souls — was the census, compiled once a year, usually at Easter, that recorded the parishioners in the jurisdiction of the parish priest. The Church set out the exact data to be collected from each individual, specifically their name, surname, age, description of family affiliation and list of sacraments received. The information gathered in these parish family books is fundamental in reconstructing the lives of the violin makers of Cremona in the 17th and 18th centuries.

My patience was rewarded as I found what I was looking for and was finally able to confirm that the parish priest had not been mistaken when he referred to Antonia Maria as “Costa”. I also uncovered the reason she could have never run a business with her brothers. I presented these discoveries in my biography of Stradivari, which was published in German in 2021.

“Stradivari – Die Geschichte einer Legende” by Alessandra Barabaschi, published in 2021.

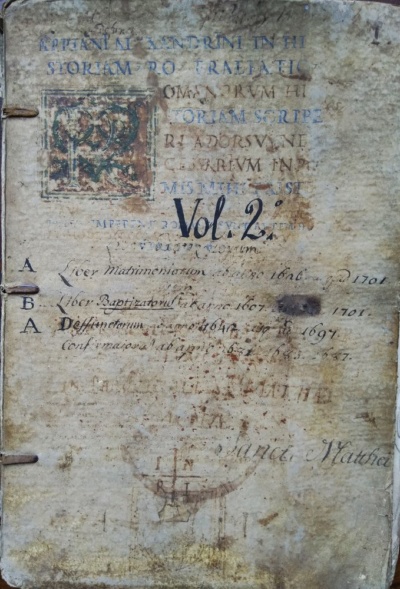

For decades, a register from the parish of S. Matteo was thought to have been lost, but a couple of weeks ago it reappeared. The information it contains, such as Antonia Maria Zambelli’s birth certificate, allows us to complete her family tree.

The parish register of S. Matteo, which has recently reappeared. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

The parents of Antonia Maria Zambelli

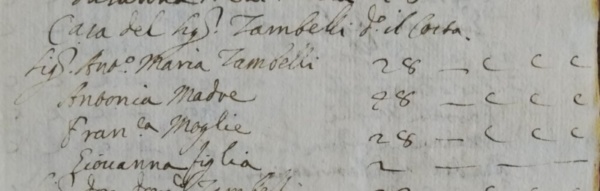

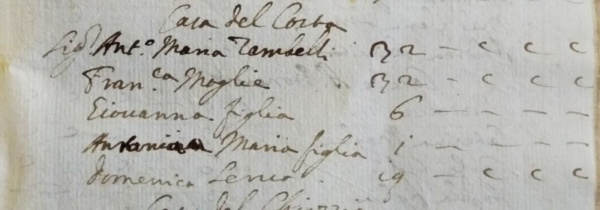

Antonia Maria Zambelli was named after her father, Antonio Maria Zambelli, as well as her paternal grandmother, who was also called Antonia. This can be deduced from the State of Souls of 1661 and 1662, where an Antonia, aged 48, was registered as “madre” (mother) of Antonio Maria Zambelli, aged 28.

Next to the name and age of the listed persons, the sacraments received were also recorded. In the case of adults, three Cs appear (C., C., C. = Confession, Communion, and Confirmation). Status animarum of the parish S. Matteo, VI-2, 1662, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. Approval no. 1664/BCE/E/2023. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

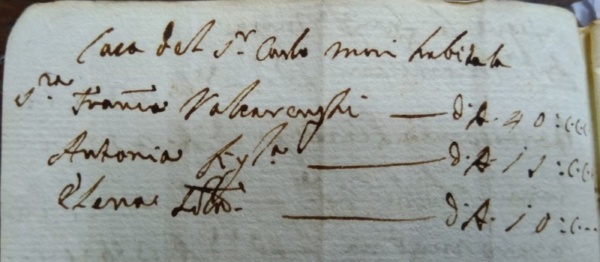

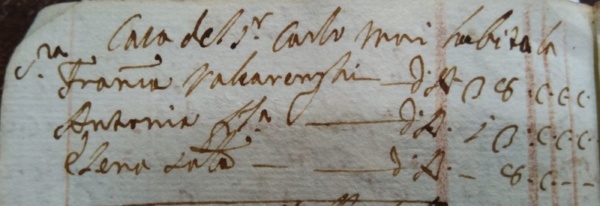

Antonia Maria’s mother was named Francesca and was almost always recorded in the Status animarum by her maiden name, Francesca Valcarenghi, on account of the fact that her husband died relatively young.

On some occasions, confusingly, Francesca is also referred to with the surname “Costa”. In order to retrace the fate of her children, including Antonia Maria, one had to look for the surnames Valcarenghi and Costa, not Zambelli. This is another reason why the background of Antonio Stradivari’s second wife hadn’t been uncovered until now.

An example of Antonia Maria’s mother recorded as “Valcarenghi“. State of Souls of the parish S. Donato, IV-16, 1680, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

The siblings of Antonia Maria Zambelli

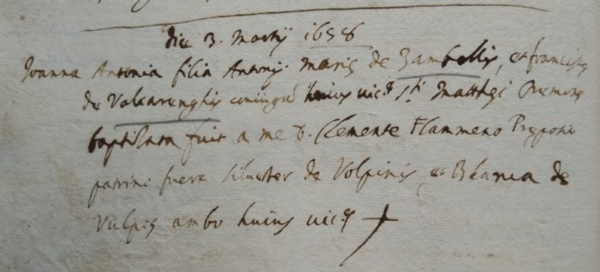

The Zambellis had a first daughter, Giovanna Antonia, born on March 2, 1658, and baptized the following day.

The birth certificate of Giovanna Antonia Zambelli, born on 03/02/1658. Baptismal register of the parish S. Matteo, newly recovered, 1658, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

Unfortunately, she survived only five days.

The death certificate of Giovanna Antonia Zambelli. Register of deaths of S. Matteo, newly recovered, 1658, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

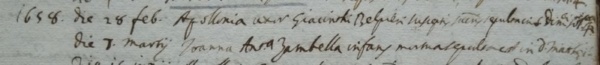

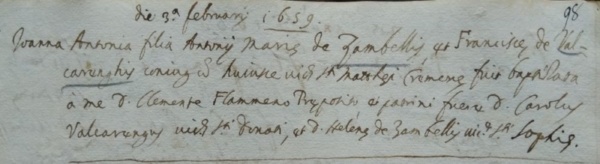

Less than a year later, in early February 1659, a second daughter was born, who was also given the name Giovanna Antonia.

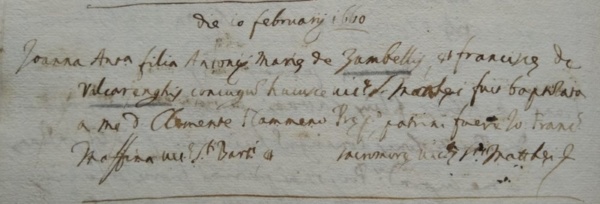

The birth certificate of Giovanna Antonia (II) Zambelli, baptized on 02/03/1659. Baptismal register of the parish S. Matteo, newly recovered, 1659, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

Infant mortality was very high at this time and, following a widespread custom, parents often gave a newborn the name of the sibling who had passed away at a young age. We see this in Stradivari’s life wherein his second son was named Giacomo Francesco (1671-1643) after his brother Francesco passed away shortly after his birth. [1]

As Giovanna Antonia (II) also died young, the third daughter of the Zambellis, born in early February 1660, was likewise baptized Giovanna Antonia (III).

The birth certificate of Giovanna Antonia (III) Zambelli, baptized on 02/10/1660. Baptismal register of the parish S. Matteo, newly recovered, 1660, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

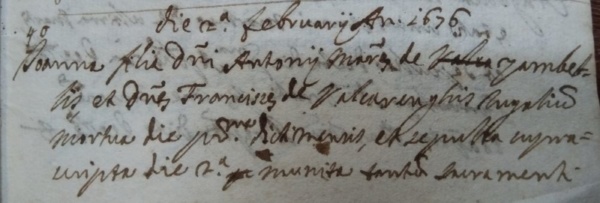

This name clearly did not bring luck to the family as this third daughter also did not reach adulthood. She died in 1676 at the age of sixteen.

The death certificate of Giovanna Antonia (III) Zambelli. Register of deaths of S. Donato, IV-1, 1676, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

When was Antonia Maria Zambelli born

After three Giovanna Antonia came Antonia Maria Zambelli.

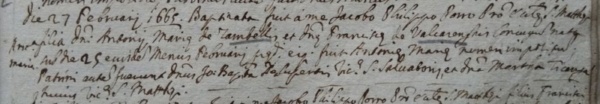

Contrary to the existing sources thus far, she was not born on June 11, 1664 [2], but on February 25, 1665.

The birth certificate of Antonia Maria Zambelli, baptized on 02/27/1665. Baptismal register of the parish S. Matteo, newly recovered, 1665, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

When she married Antonio Stradivari, she was 34 years old, about 20 years younger than the famous violin maker.

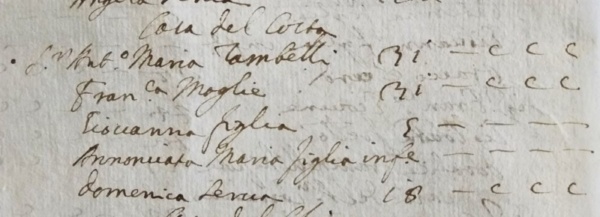

The priest had correctly recorded her in the 1665 Status animarum as “infante” (infant) but under the wrong name “Annunciata Maria”.

Antonia Maria Zambelli mistakenly recorded as “Annunciata Maria”. State of Souls of the parish S. Matteo, VI-2, 1665, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

How can we be sure that it was our Antonia Maria, meaning Stradivari’s future wife? Because, the following year the mistake was identified and the same person who again had erroneously noted her name as “Annunciata,” corrected it to “Antonia.”

The child’s name was corrected from “Annunciata Maria” to “Antonia Maria”. State of Souls of the parish S. Matteo, VI-2, 1666, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

In 1666, Francesca Valcarenghi gave birth to her fifth daughter who was named Elena. She appears to have been Zambelli and Valcarenghi’s last child. And this is why Antonia Maria Zambelli could not have run a business with her brothers, because she had none, only sisters.

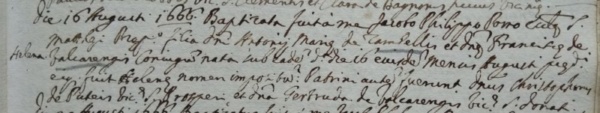

The birth certificate of Elena Zambelli, baptized on 08/16/1666. She was the last child of Antonio Maria Zambelli and Francesca Valcarenghi. Baptismal register of the parish S. Matteo, newly recovered, 1666, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

From 1678, Antonio Maria Zambelli’s name no longer appears in the annual census and his wife Francesca is registered under her maiden name Valcarenghi.

Antonio Maria Zambelli is no longer recorded from 1678 on. State of Souls of the parish S. Donato, IV-16, 1678, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

It would seem that Antonio Maria had died, a fact also confirmed by Antonia Zambelli and Antonio Stradivari’s marriage certificate. The bride is listed there as “figlia del fu signor Antonio Maria,” meaning daughter of the deceased Antonio Maria Zambelli.

The marriage certificate of Antonia Maria Zambelli and Antonio Stradivari. Marriage register of the parish S. Donato, III-2, 1699, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

The dowry of Antonia Maria Zambelli

In 2012, Gianni Toninelli discovered the dowry certificate of Antonia Maria Zambelli, ending one of the many debates circulating among Stradivari scholars, between those who claimed that Zambelli’s dowry was only an informal document and those who were convinced otherwise [3]. The latter based their conviction on the fact that the dowry of Stradivari’s first wife, Francesca Ferraboschi, was also documented in a notarial deed, proving the care with which Stradivari managed all his affairs.

This second dowry certificate was signed by Stradivari and Giovanni Battista Valcarenghi, the maternal uncle of Antonia Maria Zambelli, since her father had already passed away. Stradivari’s son-in-law, the notary Giovanni Angelo Farina, who had married his daughter Giulia Maria, took part in these negotiations as a second notary, or an additional guarantor, so to speak.

The dowry of Antonio’s first wife, Ferraboschi, had consisted of 300 lire in cash and just under 1,500 lire in goods, that is, clothing and household items. In the case of Zambelli, her dowry amounted to 3,254 lire. The nine pages that make up the document list refined dresses, jewels, furniture, and even twenty 20 paintings, revealing that underscore the bride’s eclectic tastes as well as her wealth. Although a large part of this was household goods and jewelry rather than cash, all in all it was a distinctly superior dowry to that of Ferraboschi. The wealth of the Zambelli family is also confirmed in the Status animarum. For as long as Antonia Maria’s father was alive, a maid was hired practically every year to support the family.

A turning point in the couple’s relationship?

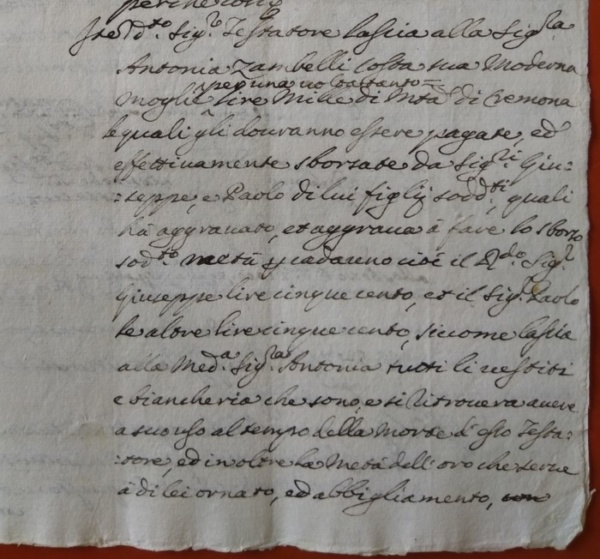

From the many versions of Antonio Stradivari’s will discovered by Carlo Chiesa and Duane Rosengard[4], a complicated picture of the relationship of the last years between Antonio and his wife emerges.

In the first version of his will, Stradivari had not even allocated anything to his wife. Antonia Maria would have been allowed to remain in the Stradivari family home, and her stepson Francesco would have had to take care of her.[5] Quite startling after more than thirty years of marriage!

However, in the final will, Stradivari determined that his sons Giuseppe and Paolo should pay their mother the sum of 1,000 lire in cash. This means that Zambelli would not inherit directly from her husband’s estate. Instead, only through her children could she access her share of the inheritance. Moreover, Stradivari specified that, as in the case of his daughter Caterina, his wife could keep all her clothes, her linen, but only half of her jewelry. Again, this is a small but significant detail. At the end of the paragraph dedicated to his wife, Stradivari explained that this bequest was in gratitude for the affection she had always shown him. But he also expected her to remain a widow and live honestly and chastely in his house.

A detail of Antonio Stradivari’s last will. Notarial archives, notary Giovanni Pietro Prati, April 6, 1729, record 6390, Archivio di Stato, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

Stradivari seemed either unsatisfied by or perhaps jealous of his much younger wife, who would receive nothing at all from his inheritance if she decided to remarry. Zambelli, however, died before her husband and was therefore unaware of these clauses in his will. From this point of view, at least, a small consolation.

Why was Antonia Maria Zambelli referred to as “Costa”

How can we explain the mystery of why the priest recorded Antonia Maria Zambelli as “Costa” in her death certificate? For that, we have to step back in time.

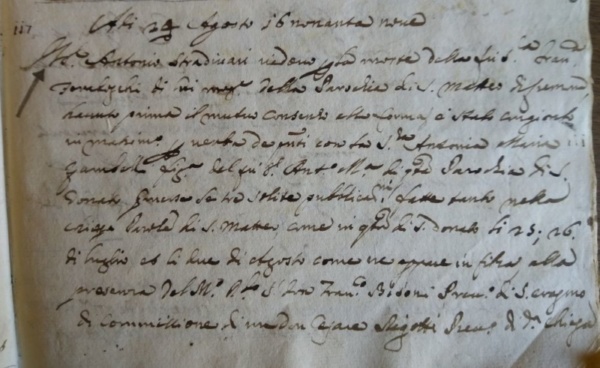

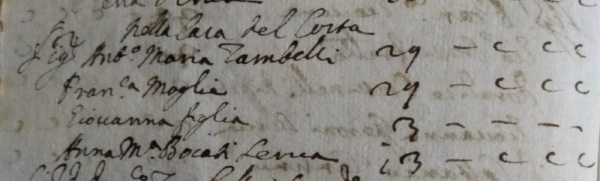

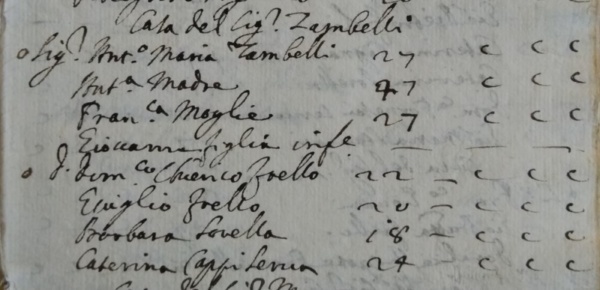

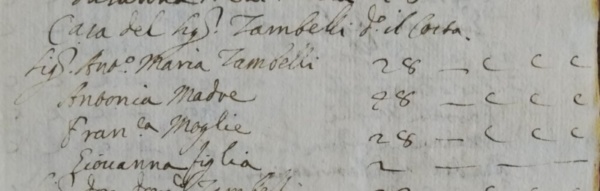

From 1659 onwards, Antonio Maria Zambelli and his family were repeatedly listed in the Status animarum as residents of the “Casa del Costa”.

Antonio Maria Zambelli and his family lived in the “Casa del Costa”. State of Souls of the parish S. Matteo, VI-2, 1663, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

Was the house rented or owned? I found the answer in the 1661 census where, instead of “Casa del Costa” (Mr. Costa’s house), “Casa del Signor Zambelli” (Mr. Zambelli’s house) was listed.

State of Souls of the parish S. Matteo, VI-2, 1661, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

Did Antonia Maria’s father buy the house from a Mr. Costa? Apparently not, since it was already his property. In fact, in 1662 the family lived in the same house, described at that time as “Casa del Signor Zambelli detto il Costa” (House of Mr. Zambelli known as Costa).

Nicknames were quite common at the time and could be used for several members of the same family over generations. A similar example can be found in the Ruggeri family, where not only Francesco but also other members were given the nickname “il Per”.

This record shows that Mr. Zambelli was also called Costa. State of Souls of the parish S. Matteo, VI-2, 1662, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Cremona. (Photo: Alessandra Barabaschi)

In the following years through to 1666 inclusive, the Zambelli house is referred to by the name “Costa”. This explains why the priest called Stradivari’s second wife in her death certificate “Antonia Costa Stradivari”. For him, the surnames “Zambelli” and “Costa” were equivalent. As Sherlock Holmes would say, “Elementary, my dear Watson!”

We may not know what Antonia Maria Zambelli looked like, but there is no doubt that she spent 38 years of her life on the side of the most famous violin maker of all time, bearing him several children, who also contributed to his immortal fame.

Thanks to Valeria Leoni, don Paolo Fusar Imperatore and don Gianluca Gaiardi for their kind support.

Alessandra Barabaschi is an art historian and has authored several books including the biography “Stradivari – Die Geschichte einer Legende”.

Notes:

- He was baptized on 02/07/1670, but the baptismal register has been lost. He died on 02/12/1670. According to the register of deaths, he was eight days old. Therefore, we can presume that he was born on February 5.

- Paolo Lombardini, Cenni sulla celebre scuola cremonese degli stromenti ad arco non che sui lavori e sulla famiglia del sommo Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, 1872.

- Notarial Archives, Notary Facio Angussola, December 4, 1699, Record 5702, Archivio di Stato, Cremona.

- Carlo Chiesa and Duane Rosengard, The Stradivari Legacy, London 1998.

- 1st version of Antonio Stradivari’s will: Notarial archives, notary Giovanni Pietro Prati, January 24, 1729, record 6390, Archivio di Stato, Cremona.