For a long time it was thought that the oldest French instruments were those of the Pierray–Boquay school, made around 1690–1730. However, archival evidence reveals both the existence of many luthiers throughout France before this time and sales of French violins as early as the 16th century.

Certainly, we know about the 17th-century viols made by Nicolas Bertrand, whose branded examples in the Musée de la Musique de Paris are incontrovertibly authentic, as well as a pochette by Dumesnil of Paris and one by Gouttenoire of Lyon; however, there appear to be no surviving 17th-century violins or cellos apart from a handful of violins considered to be by members of the Médard family.

Early violin-family instruments depicted in a fresco from l’Abbaye St Antoine in the département de l’Isère. These frescos were made around 1360–1450. At the very bottom of the image the instrument looks like a proto-violin, hybridized with a lute

According to archival research, there were at least ten Médard luthiers who were active between the late 16th century and the early 18th century, including Claude II, Henry I, Claude III, Francis I, Antoine II, Nicolas III, Dominique and Nicolas IV. The family was from Nancy, a city located 45 km north of Mirecourt in Lorraine, but some of them would have worked in Paris. The charter of the Maker of Musical Instruments of Paris was signed by King Henry IV in 1599 and there were about 15 established luthiers in Paris at this time: Pierre Aubry, Justin Bastien (Luthier of the Duke of Bourbon), Nicolas Bertrand (Faiseur d’instruments ordinaires de la musique du Roi), Antoine Besse, Boissard, Nicolas or Romain Cheron, Michel Colichon, Claude Coquet, the Denis family, Dumesnil, Jean and Charles Hurel, Henry Mahieux, Jacques Quinot and Jacques Renault.

Decorated violin attributed to Médard in the Musée Lorrain à Nancy

Of the presumed Médard instruments, the violin in the Musée Lorrain in Nancy shows typically French work, rather rustic and with poor varnish. The top and back are probably by different makers, while the head appears to have been added later to ‘improve’ the instrument. The coat of arms of the Dukes of Lorraine on the back was probably added at a later date, while the painting on the table is classic 18th-century style.

Violin attributed to Médard in the Hospice Comtesse de Lille

The Médard violin owned by the Hospice Comtesse de Lille is covered with a thick red varnish that does not appear to be original. The f-holes, C-bouts and the corners show beautiful curves, similar to those of some old Dutch instruments. The f-holes do not seem to have been enlarged, but it’s hard to tell.

A double-purfled violin attributed to the Médard family in the Musée de la Musique, Paris

The double-purfled Médard in the Musée de la Musique in Paris also presents beautiful lines, especially in the corners and C-bouts. The f-holes have been moved and the very rustic head does not correspond to the rest of the instrument, which is very finely realized.

Clearly these three Médard violins have nothing to do with each other and it is unclear whether any of them were actually made by the Médard family. There is also a Médard in the Chi Mei collection, which is again very different stylistically.

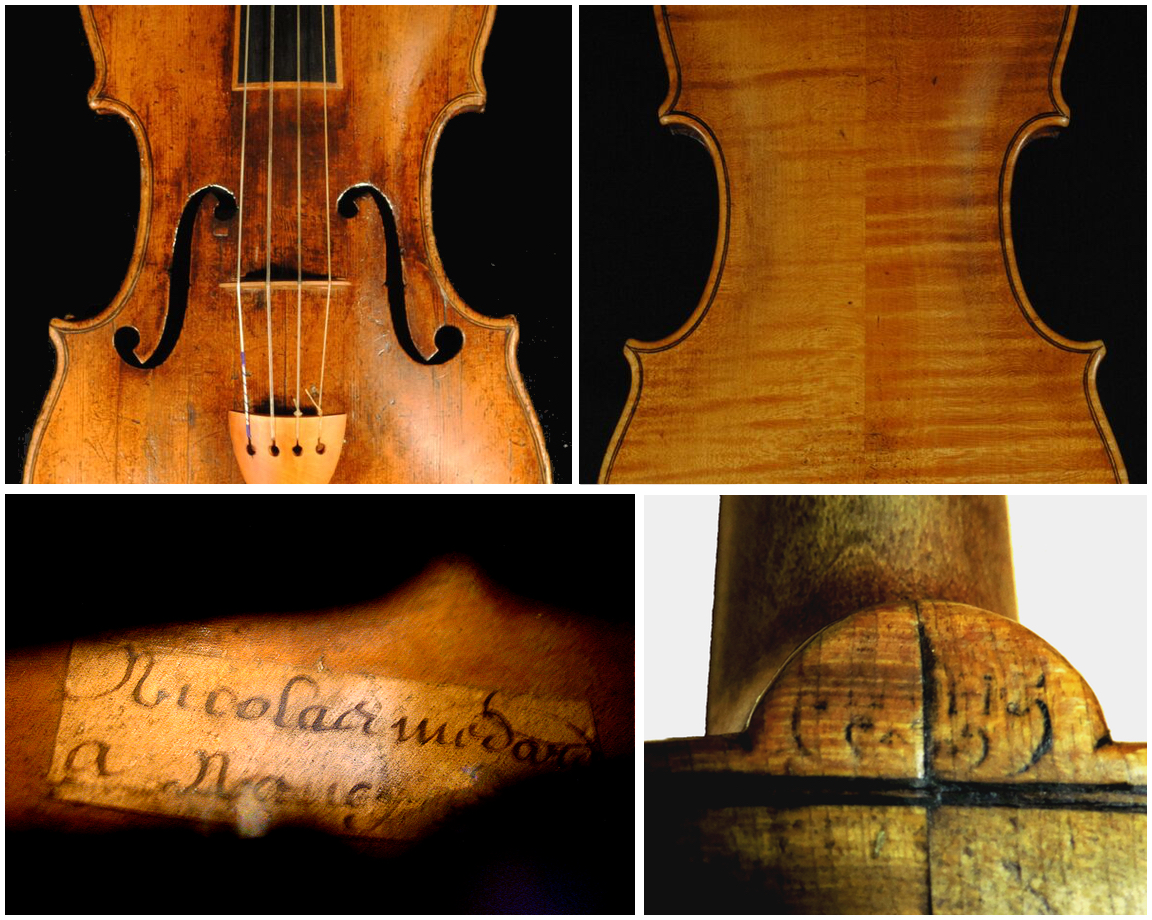

This violin with a fake Médard label is probably a later work by Nicolas Harmand

The last Médard instrument listed in the public collections in France is that of the Nancy Conservatoire de Musique. This one is very simple but, despite its Médard label, it is typical of Mirecourt around 1770–80 and is almost certainly the work of Nicolas Harmand, with his original brand on the button.

It is interesting to consult the inventory of Nicolas Bertrand’s shop made after his death in 1725, which reveals a large commercial operation. [1] The inventory indicates that, out of around 250 instruments in the workshop, there were 19 of his own viols, but no violins made by his hand. There were, however, 19 violins by Trévillot, a large family of Mirecourt luthiers active from 1645 to 1762, and more than 500 violin tables and backs waiting to be assembled. Presumably Bertrand made only a few violins himself, as none appear to have survived. I recently discovered a violin in the French style from around 1700 bearing an authentic Bertrand label, but it is unlikely to be original to the instrument because it is stuck on the belly patch.

Nicolas Bertrand label dated 1707

In Mirecourt the archives tell us that at least one luthier existed there as early as 1619, while the workshop of the luthier Dieudonné Monfort employed apprentices under contract around 1630. So although the Corporation des Luthiers de Mirecourt wasn’t created by Duke François de Lorraine until 1732, it’s clear that various dynasties of makers, including the Jacquot, Mougenot and Trévillot families, were already active from the end of the 16th century.

Perhaps some of these luthiers made only viols, lutes or mandolins, but it seems likely that the violin’s growing popularity in the 17th century had begun to create a demand for the instrument. Many writings attest that violin family instruments were indeed being made in France in the 17th century: for example in the Paris Notaries’ Archives, a merchant living in Paris named Baptiste Jolicoeur is shown as having sold a ‘basse contre de violon de Lorraine’ (a bass violin) to a Jacques Grossin on February 19, 1611.

Various inventories also record the existence of violins. One made after the death of a woman named Catherine Coysnon dated April 2, 1618 [2] (which mentions her son-in-law Martin Binart as one of the violinists at the king’s court), includes two Cremonese violins and a taille de violon de Lorraine. An inventory dated August 9, 1612 following the death of Paul Belamy, a merchant dealing in musical instruments, lists two violins from ‘Bresse’ (probably Brescia), two violins from Lorraine, four other old violins, both small and large, a ‘taille façon de Lorraine’ (an instrument of an intermediate size between the piccolo violin and the bass violin), ten bows of ‘Brezil’, and one ‘basse de violon façon de Lorraine’ with a Cremona label! Added to this, the Turin archives record that in 1523 the Treasury of Savoy apparently bought various trumpets and violins from France for their musicians. [3]

Chappuy label with a handwritten inscription of François Medard on the reverse

It is clear then that in Nancy, Mirecourt and Paris during the 17th century, French violin making was much more active than has been previously thought. Where have all these instruments gone? Either they no longer exist, or, perhaps more likely, they have lost their original identities. Interestingly, I once found the handwritten inscription ‘François Médard à Paris 1726’ on the back of an original Chappuy label; this label was glued with the Chappuy side visible in a French cello from the 18th century.

Early French instruments may well have been altered to be passed off as Italian. Often 17th-century instruments are difficult to identify – they could be Italian, French or Flemish – but interestingly, some examples are fully double-edged despite being in fairly good condition otherwise. It is as if someone had wanted to remove any traces of the groove created by the method of inserting the ribs into the back, a characteristic of the French and Dutch schools that has long been considered to be non-Italian.

School of Boquay violin from the late 17th century

Some instruments by Claude Pierray and Jacques Boquay are very easily identifiable. Pierray instruments tend to have a very beautiful model, show excellent workmanship and a rather golden-yellow varnish, while the Boquay are generally made on a heavier, less elegant model, with average workmanship and a dark varnish that is red and a little cloudy. Clearly the authors of these instruments must have had different teachers. However, we find plenty of other instruments that show characteristics of both these makers, to the point that we wonder which of them could have made it. As with many under-documented schools of violin making, it is often better not to give definite attributions in these cases, and generally the conclusion is either ‘school of Pierray’ or ‘school of Boquay’. For example the violin shown above, which dendrochronology indicates was made around 1693, is roughly contemporaneous with the work of Boquay and was probably made by someone who shared the same teacher as Boquay.

A French violin, Boquay school, with a fine red varnish

The violin shown above was made in the same style as the previous one, rather heavy, but with a beautiful transparent red varnish.

This 17th-century French cello retains its original head

This cello (above) bears the same varnish as the previous violin. It no longer has its edges, nor its original purfling, but fortunately retains its beautiful original head. Dendrochronology indicates that the table in four parts dates from 1623–1550 and 1666–1633. Very different maples have been used for the ribs, the back and the head.

A 17th-century French cello labeled Médard, with its original edges and purfling

The cello above does not have its original head, but its edges and purfling are original and it bears a label that reads: ‘Antoine Médard Paris 16…’ (the last two digits are unclear, but possibly read 1680). From the point of view of the dates this corresponds well with Antoine Médard II. The f-holes are exactly the same model as the previous cello, although their angle is different because the instrument has been shortened in the middle. I am convinced that this is by the same maker as the previous cello.

A violin reminiscent of the previous two cellos

The violin above has very different purfling, but the simplistic, open f-holes and varnish remind me of both the previous cellos.

![[Cello 3 – A31 A32 A55 A56 A57]](https://tarisio.com/content/uploads/2018/12/Cello-3-A55-1200w.jpg)

A remodeled cello, early 17th century, with Amati-influenced f-holes

The original purfling survives on this cello, which was probably made as a bass violin

The cello above, which has been entirely recut and was probably originally a bass violin, still has the original fine and narrow purfling in the C-bouts. The wood is very poor, with the back and the table both made from several parts.

Violin made from ash-tree wood. The location of the original block suggests it is French 17th-century work

The violin above is reminiscent of a small-model Brothers Amati, made from ash-tree wood, with the table in one piece, lacking its original head. The original block is integral to the neck, something that I have noticed several times in violins that I attribute to the French school of the 17th century. The dendrochronology indicates a date of 1676 and although it is reminiscent of Low Countries’ work, or perhaps Italian, experts Jan Strick and Serge Stam have confirmed that it is neither Dutch nor Flemish. Unfortunately early French instruments have tended to be incorrectly recorded as 17th-century Flemish by dendrochronology experts, which has corrupted the dendrochronology data pool, and it is time to try to correct this!

![[Violin 4 – A66 A67 A68 A69 A70]](https://tarisio.com/content/uploads/2018/12/Violin-4-A665.jpg)

French 17th-century violin with the head showing the influence of Amati

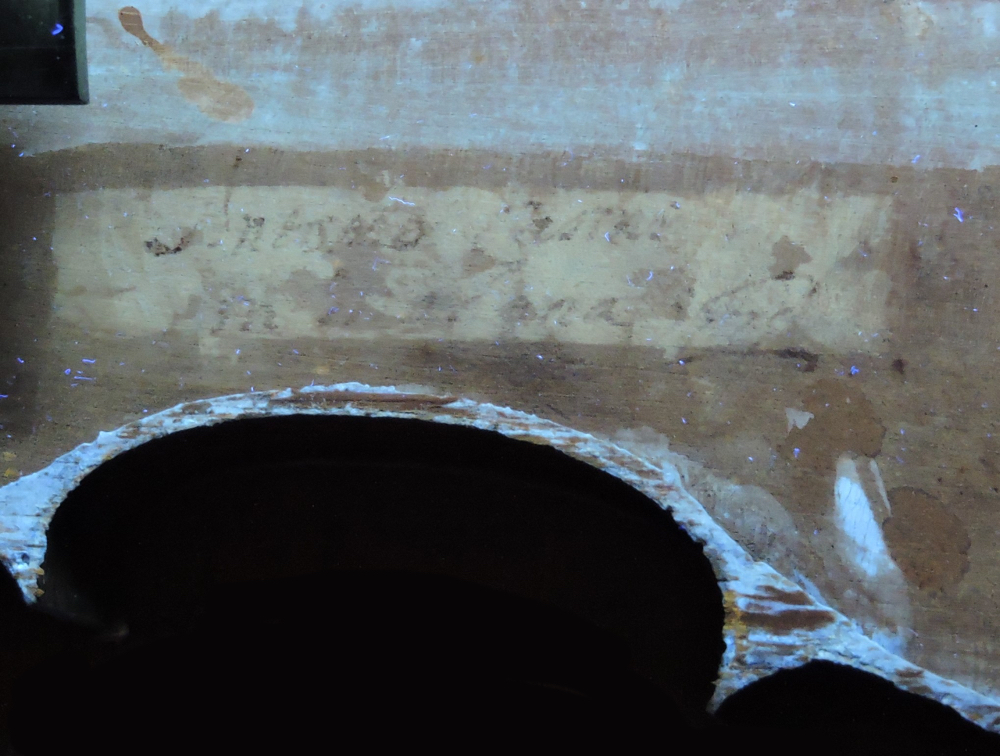

An illegible inscription was hidden under a fake Guarneri label in the violin shown above

It would be easy to imagine that the violin making schools of Nancy, Mirecourt and Paris had little in common at this time, as between Florence, Naples or Cremona. However, as Philippe Dupuy has pointed out in his research, during this period there were very strong links between the Duchy of Lorraine and the Dukes of Mantua, and also between Paris and certain Italian cities. Most famously, Andrea Amati was commissioned to make violins for the French Court of King Charles IX in 1566. In addition, during the 16th century there was a common immigration route from southern Germany through Italy to Lyon, as noted by Henri Coutagne – so luthiers, musicians and their violins traveled more than we imagine today.

Finally, as the Mirecourt specialist Roland Terrier has pointed out to me, while the names of so many early French luthiers have been lost, the fact that the Médard family has not been forgotten and their name still comes to mind when one thinks of 17th-century French violin making is largely thanks to the research into the early lutherie of Lorraine performed by Albert Jacquot from Nancy.

Marc Rosenstiel is an award-winning French violin maker who worked for many years with Etienne Vatelot in Paris.

Notes

[1] On this subject we are indebted to the magnificent work of Sylvette Millot, who has collected so many details on the life of Parisian luthiers. Milliot, Sylvette, Histoire de la lutherie parisienne du XVIIIe siècle à 1960, vol. 2: Les luthiers du XVIIIe siècle, Spa, Belgium: Les Amis de la Musique, 1997.

[2] Mentioned in Le minutier central des notaires de Paris.

[3] Carlo Chiesa, Conférence à la Ste. Cécile ALADFI, 2017.