My great-grandfather František Špidlen (1867–1916) came from a hilly region in the north-east of Bohemia (now the north of the Czech Republic) named the Giant Mountains. It was a poor area and life was ruled by a harsh climate with long winters and short summers, so the harvest yields were limited.

At this time Bohemia was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The government was in Vienna and the official language was German. Tension between the Czech people, who tended to be Protestant, and the strictly Catholic Germans and Austrians had been present for centuries.

Interestingly given these circumstances, a strong Czech cultural movement appeared in the Giant Mountains, led by Věnceslav Metelka (1807–1867). Being first a teacher and later a violin maker, he was active in literature, theater and music. As a violin maker he founded an important branch of the Czech violin making school.

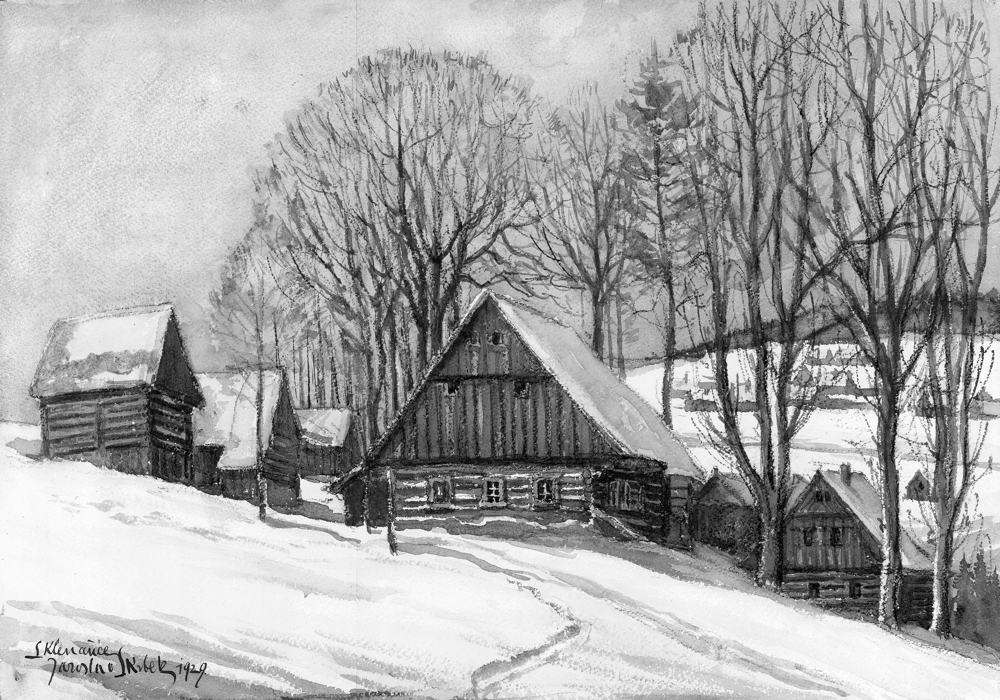

The cottage in Sklenařice where František Špidlen was born, painted in 1929

Born in the village of Sklenařice, František Špidlen was the son of a farmer and started to learn violin making from his brother-in-law, František Vitáček (1854–1901), who had married his sister Marie. Vitáček lived in the same village and himself had been a pupil of Josef Metelka, the son of Věnceslav Metelka. Špidlen apprenticed with Vitáček from 1881–1884.

The early violin pictured below dates from 1884 and shows that Špidlen followed the style and working methods of Metelka and others. The wood is local and not very handsome, although he obviously cared for detail and clean workmanship. This can be found even in the interior.

In 1886 Špidlen accepted the invitation of a fellow countryman, Jindřich Jindříšek, to work for him in Kiev (which was then part of the Russian Empire). Jindříšek was a successful businessman who ran a large department store in Kiev, which was, compared with the Giant Mountains, a cultural metropolis. Špidlen was known to him as a skilled maker and restorer, and Jindříšek employed him to lead the musical instrument department. Here he gained valuable experience in restoration, instrument making and running a business.

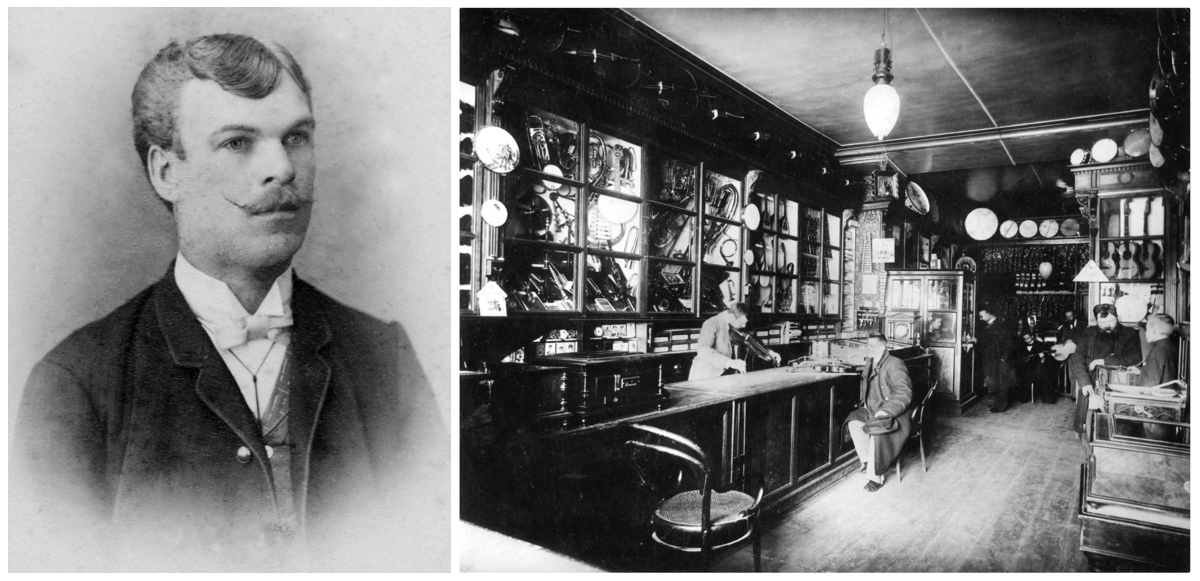

František Špidlen (left) during his time in Kiev, and (right) the musical instrument store that he ran in the city

In 1889 Špidlen was obliged to return home to undertake his military service. He stayed with the army until 1892, which luckily did not involve much fighting but instead allowed him to work ‘at the music’ (a common expression for the music department of an army, government or other organisation) in Terezín, a town in the north of Bohemia.

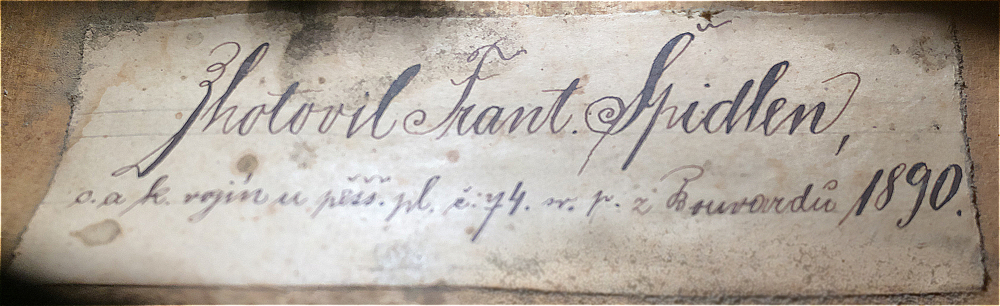

Label from a František Špidlen violin dated 1890

A violin dating from this time is labeled: ‘Zhotovil Frant. Špidlen, c. a. k. vojín u pěšš. pl. č. 74. sv. p. z Bouvardů 1890’ (Made by Frant. Špidlen, emperor’s and king’s soldier at the infantry regiment n. 74 of the free lord of Bouvard 1890). This violin still shows the influence of the Giant Mountains tradition, but now with higher and fuller arching. The varnish is of lesser quality, but perhaps Špidlen did not have access to his usual varnish in the army.

František Špidlen violin from 1890, made during his time in the army

More photos

In 1892 Špidlen returned to Kiev and continued working at Jindříšek’s store. Two years later he made himself independent and also married a Czech native, Anna Lorencová. They had four children: Otakar (1896), Marie (1898), Václav (1900) and Josef (1902).

The violin below is from Kiev, dated 1896. Now the work is much more reminiscent of the Italian style. Špidlen had evidently seen fine Italian instruments that had opened his eyes. The edge is still very soft and round, but the arching is now much more flat. The corners are nicely balanced and the soundholes are Stradivarian. The detail is clean and the shapes are smooth, as before. The attractive wood is no longer from the Giant Mountains and the rich red-brown varnish is transparent and of a high quality.

In Kiev Špidlen met other Czech countrymen including the violinist Otakar Ševčík (1852–1934), who was a professor at the Kiev Conservatory and later became famous for his teaching methods. It was he who encouraged Špidlen in 1897 to enter a competition for the post of violin maker at the Imperial Academy in Moscow, which was really the highest position he could achieve in Tsarist Russia. Špidlen won the competition, despite being only 30 years old, and moved his family to Moscow, where he was to spend the most enriching years of his life.

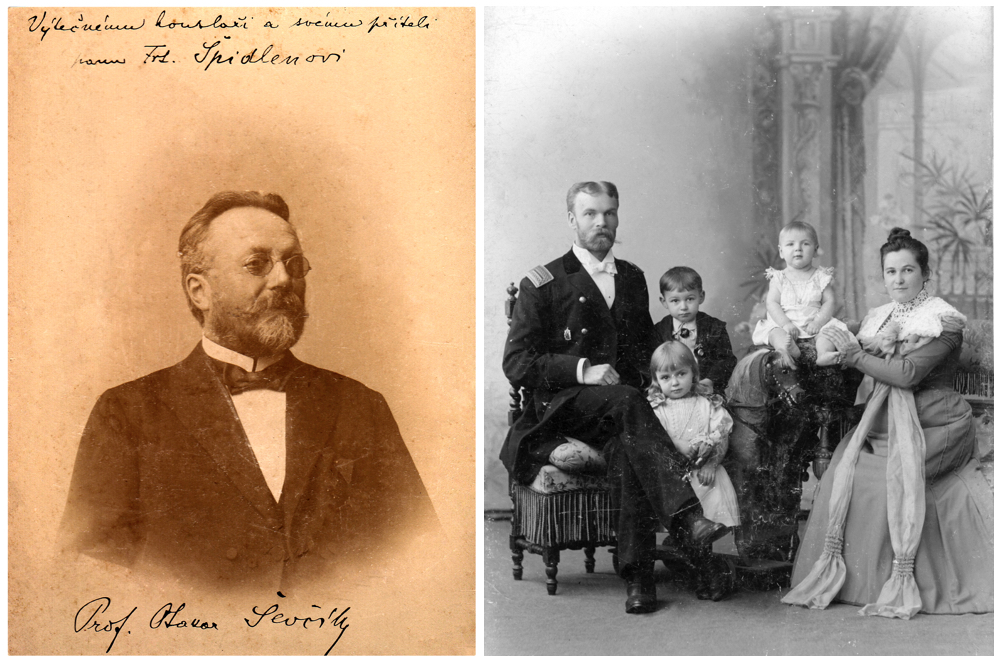

Left: Otakar Ševčík in c. 1912 (photo dedicated to František Špidlen); right: František Špidlen with his family in Moscow, 1901

Tsarist Moscow was a rich cultural city where Špidlen could meet the best players of the time and see their fine instruments. Here finally his skills could be fully used and by now he was producing first-class instruments. What progress this boy from a provincial Czech village had made in just a few years. My father, Přemysl, admired František very much, and it was František who served as an example for his own career.

The handsome violin shown below was made in Moscow in 1904 and is marked opus 112. The pattern is that of the 1740 ‘Ysaÿe’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, but the soundholes are taken from the 1743 Paganini ‘Cannon’ Guarneri. There is nothing left of the Giant Mountains style and standard. This violin equals the work of the best 19th-century makers from other parts of the world. The scroll and all other details are made with great accuracy. The red transparent varnish is of oil. According to my father’s memories, Špidlen did not make the varnish himself but instead purchased it from Germany, as did many others at that time.

Špidlen had two apprentices, both his countrymen. The first was Julius Hubička (1886–1955), who joined him in Kiev in 1902. Before this Hubička had learned with Josef Čermák, but the apprenticeship was not a success and Hubička ran home from him. This was an offence that closed the doors of all other Czech masters to him. In this sense Špidlen saved Hubička’s violin making career by accepting him as an apprentice and Hubička stayed with him until they both returned to the Czech lands.

The other apprentice was Jindřich Vitáček (1880–1946), Špidlen’s nephew and the son of his former master. Jindřich was born in Špidlen’s cottage and when his mother (Špidlen’s sister Marie) died in 1882, it was the Špidlens who brought him up. In 1895, when Vitáček was 15 and Špidlen independent in Kiev, he invited the boy there to learn violin making. Later Vitáček followed Špidlen to Moscow.

In Moscow Špidlen frequently suffered from bronchitis and his doctors advised him to move to a better climate. Therefore in 1907 he decided to return home, leaving his shop in Moscow to Vitáček, who had decided to stay. Vitáček then spent many years repaying František, and later his son Otakar, for the shop.

Špidlen did not return to Sklenařice but instead bought a house in a village named Pokratice about 100 km north of Prague, situated in the low lands, and his health recovered. He does not appear to have run a business here and we do not know of any instruments dated and marked as made in Pokratice; however, as we shall see, an increase in his production in later years suggests that during this period he probably pre-made instruments for the future.

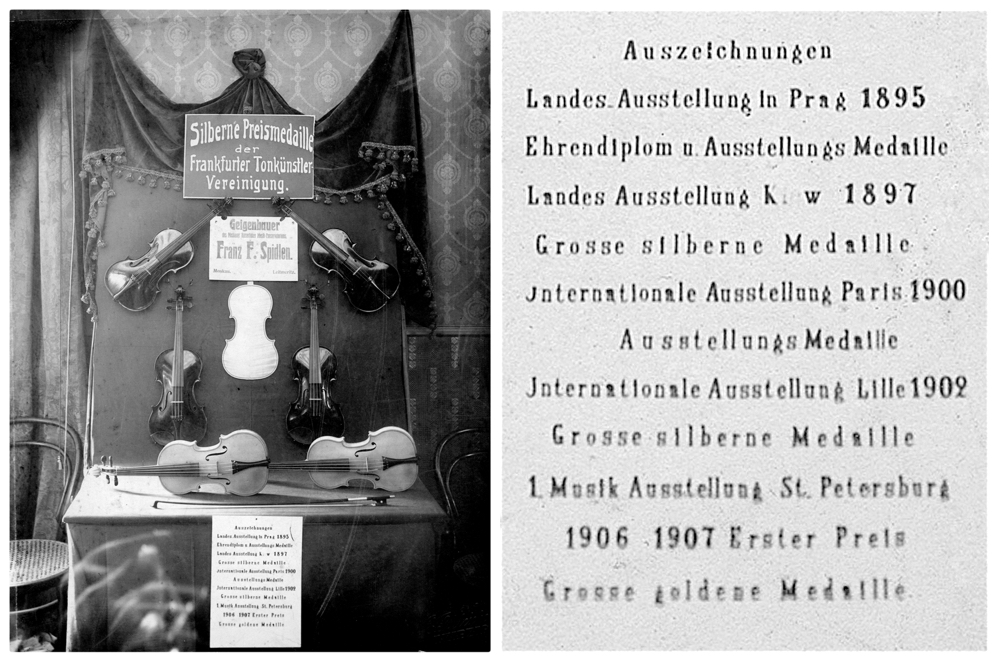

Špidlen exhibiting his instruments in 1908 in Frankfurt, where he was awarded a silver medal. Right: his display included a list of his awards since 1895

In Prague at that time the violin maker, dealer and expert Karel Boromeus Dvořák (1856–1909) was dominant in the trade, being respected and well known to all customers. However, Dvořák died in 1909 and that same year Špidlen took the opportunity to open his first shop in Prague, near the conservatory. He had one advantage – a supply of trade instruments from Vitáček, who in this way could repay him for the shop in Moscow. It was not an easy start, however, as the widow of Dvořák hired another violin maker, Georg Ullmann, and with his assistance sold many instruments inherited from Dvořák.

Despite any business issues, Špidlen’s relations with Jindřich Vitáček were always excellent, shown by a number of surviving letters between them regarding various personal and professional issues. Later Vitáček became an important source of information, as after the Bolshevik revolution in 1917 he was responsible for collecting instruments left behind by the Russian aristocracy. This is how the Russian state collection was founded and Vitáček became the curator. This of course gave him almost unlimited possibilities to study the great instruments and he shared the knowledge with the Špidlens in his letters and on visits to Prague.

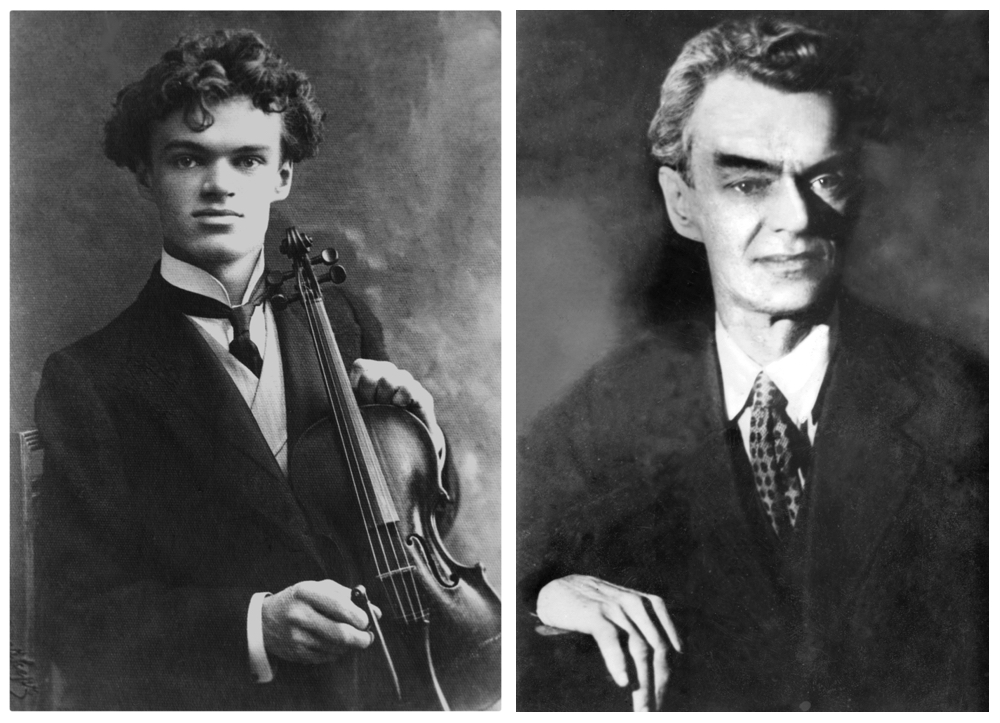

Jindřich Vitáček (left) young in Kiev and (right) around 1930 in Moscow

A comparison of Špidlen’s productive years and his opus numbers suggests that he made about five instruments a year throughout the years in Sklenařice, Kiev and Moscow. However, when he returned to the Czech lands this rises to around 10 instruments a year, most of them dated 1910. One reason could be his cooperation with Hubička. I own a viola labeled Špidlen 1911 but signed by Hubička, and some other instruments with Špidlen labels are reminiscent of Hubička’s style, especially in the interior. In addition, Otakar was 14 years old in 1910 and could well have helped his father at this age. It is significant that some instruments bearing Špidlen labels (and especially those questionable ones) are not marked with an opus number; nor they are signed and dated internally as was his practice from the very beginning. Perhaps he did not use the opus numbers and signatures for instruments he did not make completely by himself.

The violin pictured above is made after Jan Kubelík’s 1715 ‘Emperor’ Stradivari, as indicated on the label. It is also signed inside on the belly and dated November 28, 1911. The edge has a soft chamfer positioned further out, similar to that we know as the ‘French edge’. This became a typical feature of Špidlen in his later years in Prague. The detail is again perfect although the oil varnish is somewhat heavy.

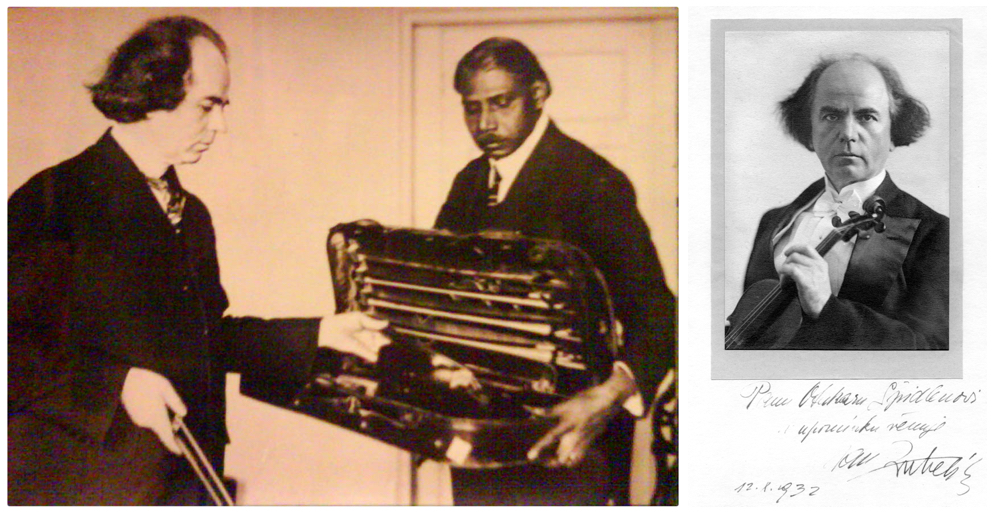

Kubelík used to come to our shop even later, after Otakar moved it to our present address. My father remembered Kubelík’s visits well and told us about his Indian servant who always accompanied him and slept in the shop on the floor if the violin had to stay overnight.

Jan Kubelík (left) with his Indian servant in the 1920s and (right) with dedication to Otakar Špidlen dated 1932

In 1913 Špidlen’s wife Anna died. He could barely manage the shop and his four children alone, and he soon married again. His new wife was Marie Slavíková, also from Sklenařice, and they had a son, František, born in 1915. Unfortunately, Špidlen’s bronchitis once again recurred and he died aged 49 in 1916, leaving the shop to Otakar, who was only 19. This was another difficult start as Otakar also had to care for his three younger siblings and was too young to formally run an independent shop. He therefore had to work under the supervision of the Czech violin makers’ society until he was old enough to become a member himself. But this is already another story.

Based in Prague, Jan Špidlen represents the fourth generation of violin makers in his family and has received various awards for his work.

All photos courtesy Jan Špidlen.