As none other, Francois Tourte was born to make bows. We must imagine him as a young man at Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges’ sensational début concert in 1772. And as an old man in 1830, at the premiere of Hector Berlioz’s ‘Symphonie Fantastique’, performed in the Paris Conservatoire, the best hall in Paris, and requiring an orchestra or more than one hundred players. François Xavier Tourte is often called the Stradivari of the bow, and his bows, like Stradivari’s instruments, may be considered works of art. From his earliest works, a pleasing visual balance is seen – they are creations beyond their intended playing functions. While almost every reference on Tourte proclaims that his importance is due to his creation of the modern bow, I believe that an equal contribution of Tourte’s was that his bows were much more than exquisite tools with which to play stringed instruments- they were often quite beautiful sculptural objects. That these are works of art is not too grandiose a description of them.

That these are works of art is not too grandiose a description of them.

The earliest Tourte we know at this time is a fluted (cannelé) violin bow, which is already moving away from the standard convex sticks of the time. The bows François Tourte made during the late 1760s and 1770s would be other fluted bows and, from about 1770, the Cramer type bow.

These are named after Wilhelm Cramer (b. Mannheim, 1 June 1746; d. London, 5 October 1799) who introduced a German model of bow when he came to Paris in 1769. Cramer seems to have stayed in France for about three years. The distinguishing element of this bow was its unique model of head in which, when viewed in profile, the back of the head mirrors the front, and is often referred to as the “battle-axe” head. The frogs were of ivory, some of them ornate and in a fashion that mimicked the heads. Not long after, some Cramer frogs had standard seatings to the sticks and were of pernambuco, olive wood, rosewood and other hardwoods, though not ebony. These Cramers caught on in Paris and were perhaps the most widely made bows for the decade of the 1770s.

Likely, the Cramer type bow did not occupy Tourte for too many years, though he could of course supply it any time upon demand. As the larger venues for concerts and the music performed there required more force- simply louder- the old stringed instruments were modified to accommodate that and newly made ones were more powerful off the bench. Tourte made bows accordingly. This moment really signifies the arrival of the exalted modern bow. The frogs were rather suddenly less tall and had gained a ferrule, which held the hair in place in a flat ribbon. Although this feature has, by oral history, been said to be through Tourte’s contact with Giovanni Battista Viotti circa 1782, it was certainly earlier, circa 1775-1780.

Tourte’s design used a metal ferrule to hold the hair in place in a flat ribbon.

By circa 1805 the hatchet head had arrived. By the time Prince Demidoff was presented his very special Tourte violin bow in 1807, Tourte had moved to 10, Quai de l’École and was highly sought after. This particular bow has a masculine hatchet head, though less angular than these would soon become.

Tourte made this bow for Prince Demidoff in 1807.

‘Cello bow heads were very rarely of the swan model now but the “violin head” type appears from time to time. The shape of the frogs was also set. The three-piece buttons differed in their silver (or gold)- ebony- silver proportions as Tourte saw fit. The frogs of the ‘cello bows often have ferrules with the flat part rounded. Bowmakers differ on Tourte’s likely purpose with these ferrules, but most regard it as an embellishment and perhaps decided upon spontaneously.

The bows circa 1805 and afterwards, previously almost all round, were now mostly octagonal until we arrive at the later bows, around 1820. Likewise, the circa 1805 date denotes a change in length to the violin and viola bows from a roughly 72 centimeter length to one of about 72.5 centimeters. About 1820, round sticks start making up about half his oeuvre, although the ‘cello bows remain mostly octagonal.

As regards contemporary expertise, we are guided by the myriad details of François Tourte’s work to establish the authenticity of his work. But also, perhaps most importantly, is the “hit”, or feeling upon first view, that we are in the presence of Tourte and a bow of his oftentimes magical creation.

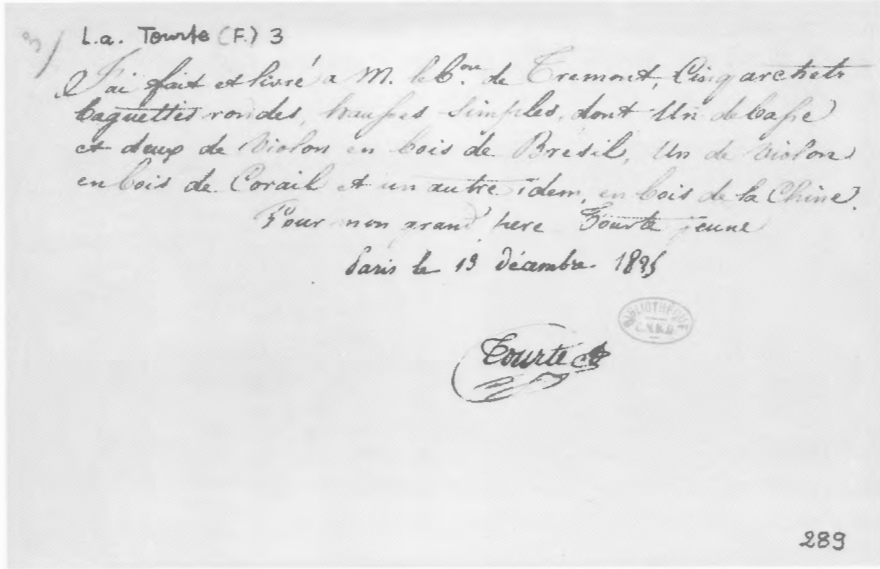

The very late bows, circa 1825 to the end, exhibit creative resilience in some, both in model and assuredness of hand, though a decline in others. But even the very last bows pictured herein show an artist engaged to the fullest until he worked no longer. Of course, he chose the very best pernambuco available. (The Baron de Tremont notes and itemized receipts inform us that Tourte also used Brazilwood, coral wood and amourette). It is very possible that our great man’s supply came, for perhaps many years, from François Delion, his landlord on the Rue du Chantre and a merchant of wood.

“I made and delivered to M. the Baron de Tremont, five bows with round stick, “simple” frogs of whcih one ‘cello and two violin in Brazilwood, a violin in coral wood and another in amourette.” – Henry Tourte (13 December 1825) Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Apart from the very early frogs of ivory and a few exotic hardwoods, the great majority of Tourte’s frogs were of ebony. We also see a few ivory frogs, circa 1790. A few tortoiseshell frogs were made, elevating the price of a bow, as would gold, significantly. The tortoiseshell itself was not laminated, as they were in the frogs of subsequent makers. This “natural shell” was harder and often not as attractive as one sees in the laminated tortoiseshell frogs of later makers. (Personal communication: Jean-Jacques Millant, 1989) It also was of a less thick measure in its flanks which Tourte remedied with ebony “sandwiched” between the two outer layers.

The ebony of Tourte’s frogs is of a high quality- dense and dark black. Rarely does one see a brownish streak running through it. The silver was of the highest quality available and not from melted down coins of the period. Gold likewise was of a high quality, 18-carat.Tourte bows have many physical traits we use to determine their authenticity, some of them unique to him. The head mortices, not newly established by Tourte but necessarily larger in order to hold more hair than the small heads of the fluted, mostly pike head bows of the Baroque era, were exactingly made, and are rather complicated affairs. Looking in, we see six separate flat shapes (though the rear one is often undercut, resulting in a sort of backward curve), tidily executed and arriving at the rather shallow and flat base.

Looking in, we see six separate flat shapes (though the rear one is often undercut, resulting in a sort of backward curve), tidily executed and arriving at the rather shallow and flat base.

For the most part these Tourte mortices were not followed by the ensuing generations of makers. The heads themselves, when viewed straight on, are slightly taller on the right, or player side. This is as easily seen looking from the handle end of the bow.

When seen straight on, the center ridges veer to the right and then center at the beak. In a few later bows (left) the ridges move in the opposite way.

The heads’ ridges rather swim their way downwards, centering at the beak.

The heads’ ridges rather swim their way downwards, centering at the beak. Again looking straight on, they veer to the right, before the centering. In a few late bows (numbers 89 and 90) the ridges move in an opposite way. These descriptions of the heads and ridges are the expressions of Tourte’s working mannerisms.

The profile often reveals a slight forward “bump” along the ridge about two-thirds of the way up.

Also good to see in the profile of many heads of the violin and viola bows, is a slight forward “bump” along the ridge, found about two-thirds of the way up. This is certainly a pronouncement of Tourte’s conscious sculptural intent.

Along the line of the back of the head are two extremely subtle “creases” or divots.

In counterpart, though almost certainly without sculpture in his mind, and not necessarily on the same bows, observed in the curve to the back of the head, are two “creases”, almost divots, which are usually extremely subtle – the result of Tourte’s carving.

The audience side chamfer is often wider and almost always faces outward more than its counterpart.

The chamfers are particularly revealing. The audience side one is often a bit wider and almost always faces outward more than its counterpart.

The chamfers are particularly revealing. The audience side one is often a bit wider and almost always faces outward more than its counterpart. Faint knife marks are normally in evidence, but more telling are the traces of the needle files, sometimes very faint. And the backs of the heads also have myriad file marks, more prominently on the later bows, often presenting a rather scratchy appearance.

Although the above details are necessary for purposes of expertise, a François Tourte bow is much greater than the sum of its parts- a veritable work of art.

Tourte can be purchased from magicbowpublications.com.