I am pleased to offer an advance preview of some highlights from our March auction. It’s a diverse and dynamic group, filled with a variety of excellent instruments, bows and vivid stories. This week I discuss violins by Tommaso Balestrieri, Carlo Giuseppe Testore, and Jean Baptiste Vuillaume and a cello by Romeo Antoniazzi and a viola by Vittorio Bellarosa. I’ll discuss several other instruments and bows in part two, coming next week.

In this video, Tarisio’s Founder, Expert and Director, Jason Price, takes a look at an exceptional violin by Tommaso Balestrieri, one of the most sought-after violin makers of the late 18th century.

Tommaso Balestrieri, Mantua, c. 1770-72

Tommaso Balestrieri (1713-1796) is one of the most sought after late 18th century violin makers. His instruments are bold, modern, Stradivari-inspired, and beautiful; until recently, his origins and background were, for the most part, unknown. Tommaso ‘Balastrelli’ was born in the hills outside of Piacenza region and it’s safe to say that his background was humble, probably from a farming family. Around 1730 he moved to Mantua and took up work as a valet, or footman, for a nobleman, and he stayed in service for the next two decades. Since the Medieval era, Mantua had been ruled by the Gonzagas, an important noble family with strong ties to culture, the arts and music. But in the early 18th century the city fell under Habsburg rule and the political, social and cultural power structures shifted dramatically.

This Balestrieri violin from c. 1770-72 is a highlight from our March auction.

From a violin making perspective, Mantua was a late bloomer. The first important violin maker in Mantua was Pietro Guarneri, who moved there from Cremona sometime in the early 1680s. Trained in the family workshop as a violin maker, Pietro took up employment in Mantua as a musician, only occasionally exercising the family business of violin making.. While the few violins that Pietro did make served as formative inspiration for the makers who followed, Mantua nevertheless lacked a continuous tradition, a distinction which set it apart from other violin making hubs. The traditional father-to-son or teacher-to-student traditions of Cremona, Milan, and Venice created enduring regional styles, but in Mantua there was very little – if any – connection between the generations. But what they lacked in continuity and consistency, the Manutan makers made up for in personality and in an entrepreneurial spirit. Perhaps this is what emboldened Balestrieri to claim to be ‘Cremonensis’ on his labels, a fact we now know is not true. And perhaps the freedom from a traditional education led him to choose a model which emulated the broad, flat patterns of Stradivari instead of the more Amatise model of Camillo Camilli who was active in Mantua before him. Even though he came to violin making late in life and evidently without traditional training, Balestrieri was hugely prolific, by far the most productive maker in Mantua during his lifetime and well beyond.

In 1965 this violin was sold by Rembert Wurlitzer to the Polish-American violinist and Holocaust survivor, Isaak Szklanka. Four years later he upgraded to the ‘Earl of Falmouth’ Bergonzi, and William Moennig & Son sold this instrument to another Polish-American soloist, Adam Han-Gorski.

In Heifetz’s class, Han-Gorski is second from the left.

Han-Gorski was born Arno Leon Hahn in Soviet occupied Lwów, Poland on March 26, 1940. Before the war his mother had been a pianist and his father a journalist. For much of World War II, the young Adam was sheltered and hidden, separated from his parents; to escape arrest by the Nazis his father assumed the identity of Tadeusz Górski. In 1945, the Han-Gorskis settled in Bytom, a small town near Krakow where Han-Gorski took up the violin. Three years later, he made his debut with the Silesian Philharmonic Orchestra. In 1955 he was the youngest participant and prize winner at the International Music Competition in Warsaw. In 1961 Han-Gorski went to Los Angeles to study with Jascha Heifetz at the University of Southern California. He later served as concertmaster of the Minnesota Orchestra, and, for 25 years, as concertmaster of the Vienna Radio Orchestra until he retired in 2004. After sixty years with this Balestrieri, Han-Gorski is ready to leave it to a soloist of the next generation.

Han-Gorski playing for Heifetz in c. 1962 as part of the Heifetz Masterclasses.

This violin is featured in the forthcoming book, The Violin Makers of Mantova by Philip J. Kass and Andrea Zanrè. I will be interviewing Kass and Zanrè about their ground-breaking research on Balestrieri and the other makers of the Mantuan school in the Carteggio to be published March 17.

Carlo Giuseppe Testore, Milan, c. 1695

This fine violin dates from the best period of Carlo Giuseppe Testore’s production. We know from his earliest labels that Testore (c. 1660-1716) trained with Giovanni Grancino; by the early 1690s he had already established his own workshop on Milan’s Contrada Larga. Testore’s early instruments are reminiscent of Grancino but carry themselves with a boldness and flair. The slanted and precisely executed soundholes prefigure Guarneri violins of the 1730s and the egg shaped volutes are distinctive. The arching is moderate – never too high – and the varnish is customarily an attractive dark reddish-brown. As with most Milanese makers, Testore rarely used highly figured maple, tending instead towards more humble, perhaps local stock. But these instruments work and most tellingly, musicians favor them.

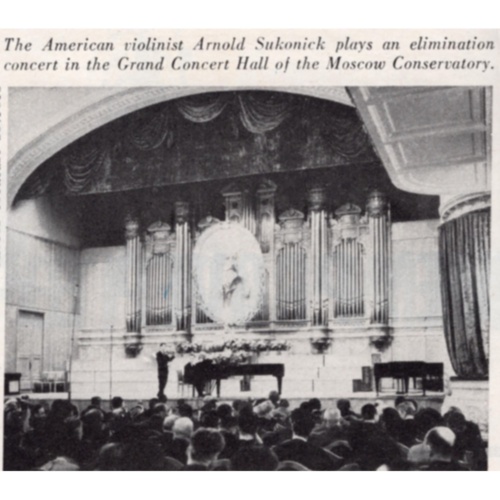

In the late 19th century this violin was owned by the English violinist and collector George Haddock. An influential teacher in Leeds, Haddock owned several important instruments including the 1715 ‘Kubelik’, the 1703 ‘Ford’ Stradivari, and the 1734 ‘Haddock‘ de’ Gesù. Upon Haddock’s death in 1907, his son Edgar, also a violinist, inherited the collection’s remaining instruments, including this Testore. Edgar later sold this Testore to George Hart who in turn sold it to the Hills. In 1914 the Hills sold it to Evelyn Kitson (1893-1988), the second daughter of the 2nd Baron Airedale, for 330 pounds on the recommendation of Arthur Bent, Kitson’s teacher at the Royal College. Some time later Kitson emigrated to Australia, but it seems the violin remained in Britain. In 1948 it was in the possession of the Scottish maker and dealer Henry B. Briggs of Glasgow. By 1954 it had traversed the Atlantic and was sold by William Moennig & Sons in Philadelphia to the 21 year old violinist, Arnold Sukonick, a talented student of Toscha Seidel who in 1962 travelled to Moscow to participate in the 2nd Tchaikovsky Competition. The violin is currently being offered for sale by Sukonick’s heirs.

Arnold Sukonick in Moscow at the 1962 Tchaikovsky Competition.

This violin is accompanied by certificates from William Moennig & Son, J. & A. Beare, Ltd, and Tarisio. The violin was illustrated in the 1995 Journal of the Violin Society of America which featured Carlo Chiesa’s biographical survey and of Milanese makers and Philip J. Kass’s cataloging of iconic examples.

Jean Baptiste Vuillaume, Paris, 1864

In 1855 the ‘Messiah’ Stradivari, perhaps the most famous of violins, came into the possession of J. B. Vuillaume (1798-1875) in Paris. Over the next twenty years, he made many excellent copies of this instrument including this handsome example from 1864. Vuillaume’s interpretations of the ‘Messiah’ model are among his most sought after works: the workmanship is impeccable, the materials first class, and his fidelity to the original design is certainly the most advanced of any copyist that came before him. The ‘Messiah’ model is unique, mostly owing to the sound-holes which are set slightly wider and somewhat more inclined than is typical for a Stradivari model.

In the animation below I’ve overlaid the sound holes of this 1864 violin over a grayscale image of the 1716 original.

In 1974 this violin was purchased by the Canadian violinist and teacher, Dr. Lise Elson. An influential teacher and faculty member at the University of Calgary, Elson also owned two Stradivari instruments at various points in her career, the 1702 ‘De La Taille’ and the 1735 ‘Nestor, Leveque, Rode’. Dr. Elson sold this Vuillaume to her pupil and later colleague, Cenek Vrba, who subsequently became concertmaster of the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra, a position he held for 36 years until his retirement in 2011.

Professor Lise Elson of the University of Calgary’s music department playing the violin with Elfie Gluesteen on piano by M. L Smith. (Courtesy of Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary).

Romeo Antoniazzi, Milan, 1912

The Antoniazzi brothers were the driving force in Milan at the turn of the 19th century. Their father, Gaetano, probably studied with the Ceruti family in Cremona but settled in Milan around 1870. Romeo and Riccardo were both violin makers but their work is distinctive and easily differentiated. The instruments of Riccardo (1853-1912), the older brother, are more exacting and precise and they were often made with aesthetically more attractive tonewood. Romeo (1862-1925), who made this cello in 1912, had a more fluid style. His instruments are less refined but full of character, and are equal or even superior tonally to those of Riccardo.

The head of this instrument is characteristic of the Antoniazzi style: deep fluting, a large, round volute, and a beautiful, clear amber-brown varnish.

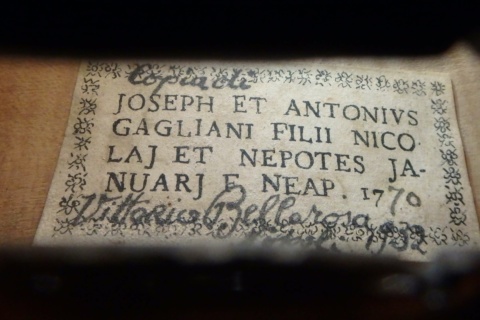

Vittorio Bellarosa, Naples, 1932

Neapolitan violin makers have a long tradition of copying and imitating the generations that came before them. Sometimes this is done for sport, and sometimes for deception. The craft of imitating allows a maker to show off his skills and for Neapolitan makers in particular it demonstrates the deeply entrenched pride that they have for Neapolitan violin making. As a point of comparison, the 20th century Milanese makers rarely copied Grancino or Testore but every Neapolitan maker since Nicolo Gagliano has copied Nicolo Gagliano. During the 20th century the best copies were made by Sannino, Pistucci, and Vittorio Bellarosa. The youngest of the gang, Bellarosa (1907-1979) is regarded as the last of the traditional Neapolitan makers.

One of the most interesting violas in our March auction is this example from 1932. At 42.0 cm it is a violist’s dream: powerful yet full of character and confidence. The label tells us it was made as a copy of Joseph & Antonio Gagliano but in actuality it feels more like inspiration than imitation. The front presents the traditional Gagliano-style squareness in the c-bouts and quite a strong asymmetry across the sound-holes. Just like faces, we’re often more attracted to instruments which are slightly asymmetrical. The treble sound hole is a full 3mm lower than the bass giving it a compelling and strong personality.

The blacks of the purfling are made out of paper in the Neapolitan tradition. The treatment at the back of the head is also typically Neapolitan: a small button with kidney shaped side-by-side channels is isolated from the main fluting at the back of the head.

Part two of our March Auction highlights will be avaible next week.