In a letter addressed to the violin virtuoso Felicien David in December 1873, Nicolò Bianchi mentions his young assistant: ‘I have a pupil living in my house for the past four years – he’s the son of an engineer of the Town of Casale Monferrato. He’s an engineer and a wealthy man himself, but he preferred to be a violin maker rather than an engineer.’

Bianchi’s assistant was Eugenio Praga (1847–1901), son of the renowned engineer Pietro Praga. At that time the town of Casale Monferrato had a growing economy and an active musical life, with a number of amateur players and instrument collectors. Bianchi had a few customers in Casale and he was probably introduced to Praga by the collector Count Zimiglio. Switching career from engineering to violin making was an unusual choice at a time when a gentleman was not supposed to use his hands to make a living, and we can deduce that the decision was not received with enthusiasm by Praga’s father. Eugenio studied engineering at the University in Florence and he must have graduated at quite a young age, since he moved to Genova to start his adventure in the violin making world in 1869.

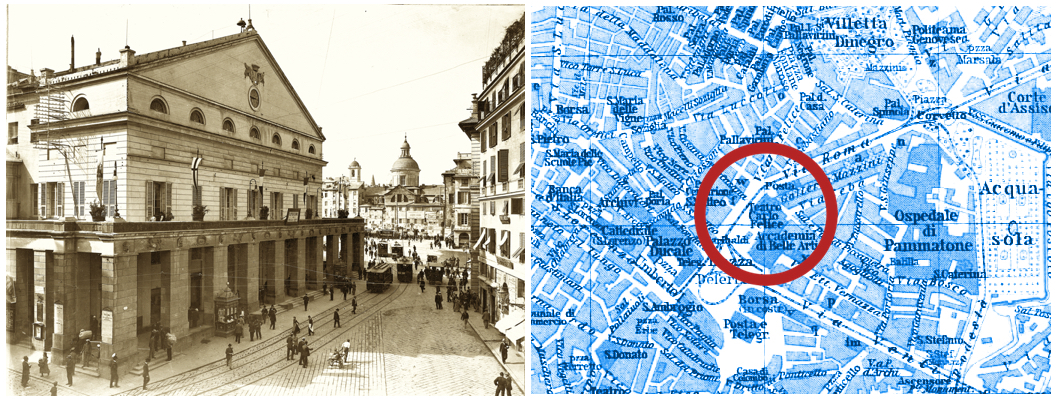

Left: the Carlo Felice Opera House in the late 1890s; right: map of Genoa in 1913, showing the location of the Opera House. Bianchi’s (later Praga’s) workshop was close by in Vico del Cetriolo although this street had been demolished by 1913

The old violin maker and his young apprentice were a mismatched pair. A man of brilliant intelligence but of scant education and rough ways, Nicolò Bianchi had an authoritarian character, while Praga was a well-educated young gentleman who was intolerant of his master’s rough discipline. In a letter to Eugenio’s father dated June 1871, Bianchi complained: ‘he’s neither an apprentice nor a factotum, he’s just a gentleman who takes lessons from me, he arrives at 10 am and gets off at 7 pm after having dinner; nobody must ever annoy him otherwise you will get nothing from him.’ Despite this, their relationship lasted until 1877, when Bianchi decided to move to Nice. He left his workshop near the Carlo Felice Opera House in Vico Cetriolo to his pupil, who from then on worked independently. During his apprenticeship Praga made a good number of instruments for Bianchi. We know he also made a quartet (possibly in Bianchi’s name) [1] for the Lutherie Exhibition held in Vienna in 1873 and it seems quite possible that he would have visited and seen the old Italian instruments showcased there.

Little information is available about Praga’s life in the 1880s and 90s. We know that he won a gold medal at the Turin Exhibition in 1884 for ‘the commendable collection of bowed instruments recognised superior to the others exhibited, and for the introduction of a special national fabrication of bows.’ It is not clear from this whether Praga presented instruments of his own or perhaps old instruments he had in his collection. We also know that his production of new bows was successful and he made a good number of bows during his career (using frogs of either French or German origin). Praga was also very active in restoration and perhaps this is another reason for his quite scarce production of bowed instruments. In the 1890s he moved his house and workshop to vico Dritto di Ponticello, a good location in central Genova and in 1892 he presented violins, violas and cellos at the Italo-American exhibition, winning a gold medal. He married Maria Caterina Freguglia in 1896 and the following year their only son, Pietro Antonio, was born.

Eugenio Praga’s signature

Despite the lack of information it seems that Praga was respected not only in Geneva but in the wider Italian violin making and music environment of the late-19th century. Browsing the old records related to the conservation of the Paganini ‘Cannon’ violin, I came across a signature at the end of a document, stating that Praga was the first violin maker to be called to take care of the 1743 Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ violin. It is perhaps not a surprise that the mayor and the assessors appointed him to this role, since besides being a violin maker, Praga was a gentleman among gentlemen.

Praga’s life ended in late August of 1901 in a village set in the hills behind Genova. We do not know the exact cause of his death, and in the obituary published by a local newspaper the journalist reported that he was surprised by Praga’s death since he was perfectly recovered, but he had slowed down his production, ‘because, lucky him, he did not need it’. [2].

It is perhaps not a surprise that Praga was appointed to take care of the ‘Cannon’, since besides being a violin maker, he was a gentleman among gentlemen

In the Italian violin making world of the second half of the 19th century, Eugenio Praga holds an important place for his intuitive understanding of classical violin making, and for developing his own personal style, which today appears to blend naturally into the Piedmontese tradition. In his hometown Casale Monferrato he may well have seen old Italian violins owned by local collectors and, even more likely, instruments by Giovanni Francesco Pressenda and Giuseppe Rocca, who both influenced his work. It’s no surprise, then, that the milieu of Casale also provided inspiration to two other great makers, Leandro Bisiach and Celeste Farotti, who sought their fortune in Milan at the turn of the 20th century.

Praga’s early instruments followed Bianchi’s directions. Their style is quite far from the antiqued copies developed during Bianchi’s time in Paris: the model is personal with a Stradivarian design; the scrolls show a small and well-rounded eye; and the oil varnish, which is of an attractive red color and a good consistency, is not antiqued. In these years Praga used a calligraphic handwritten label, indicating that he was Nicolò Bianchi’s pupil.

Soon after Bianchi’s departure for Nice, Praga started to emancipate his work from his master’s and in a few years he had developed his own personal style. His Stradivari-model violins became more rare and he instead began making copies of the ‘Cannon’. He was probably the first maker after the death of Paganini who was able to hold the violin in his hands and take accurate models of the scroll and f-holes, and his interpretations of the ‘Cannon’ stand out for their intuition, taste and balance. Like other 19th-century luthiers, Praga was reluctant to copy the original dimensions of the violin (which has a 35.2 cm back length) and he preferred a bolder soundbox, experimenting with back lengths from 35.5 cm up to 36.3 cm. He never exceeded Guarneri’s wildness and he achieved a relationship between the f-holes, archings and channelling that looks perfectly balanced and respects the original, yet is executed in a personal way. In these instruments we find Praga’s definitive label, printed on a light paper, with the printed digits ‘188-’, in which he indicates ‘premiato con medaglia’.

Praga used an internal mould like this one, with the corner blocks set on the bias. Photo: ‘Liutai Piemontesi fra XIX e XX sec. da Pressenda a Fagnola’, Consorzio Liutai e Archettai, Cremona, 1997

Praga used an internal mould with the corner blocks set on the bias and fixed the plates to the upper and lower blocks with conical pins made with hardwood: every genuine violin by Praga was made this way. Interestingly, we can see similar treatment in the work of Enrico Rocca, although the latter did not always use pins in the back, especially after 1900. Similarities between the two makers can be traced in many other details and the interiors of both can be easily confused: the blocks and linings are always made of spruce; the upper and lower blocks are well rounded; and the central linings abut the corner blocks, which are finished with an abrasive action. More similarities can be seen in the use of their models and in the stylistic flavor that seems to link the two makers, especially in their works from the 1890s.

Inlaid Praga violin based on a Stradivari model, 1892. Photos: courtesy Benjamin Schroeder

More photosWhat was the relationship between the two? They were clearly very different: one from a wealthy background who had studied extensively with a renowned violin maker; the other a working-class jack who had lost his father (and teacher) early and was trying to make a living as a woodworker on the docks of Genova. It’s unclear where Rocca received his training but one hypothesis is that, having spent the better part of his youth away from violin making, he may subsequently have helped Praga – arguably the influence of Rocca is detectable in Praga’s cellos. Also, from the correspondence of Cesare Candi we know that Praga made a pear-shaped double bass, a type of instrument that Enrico Rocca had made when he started making instruments in the 1880s and early 90s, including one from 1893 with very short corners.

The production of Eugenio Praga is relatively slight, which is perhaps why today he is not considered as he should: as one of the best Italian violin makers of the 19th century, who influenced the generation of makers that started working at the beginning of the 20th century. In particular, all the Genoese makers from Cesare Candi to Paolo de Barbieri and Lorenzo Bellafontana were significantly influenced by Praga’s style and elegant approach, particularly in his copies of the Paganini ‘Cannon’.

Based in Genoa, violin maker Alberto Giordano is assistant curator to the Paganini ‘Cannon’ violin.

Notes

[1] Bianchi wrote on October 4, 1872: ‘Ora io faccio fare un quartetto da un mio allievo per l’esposizione di Vienna’ (‘I have a quartet made by a student of mine for the Vienna exhibition’).

[2] In the original Italian: ‘perché, beato lui, non ne aveva pel [per il] bisogno’.