Author’s note: There are variant spellings of Marchioni’s name, including Dom Nicolo or Don Nicolo Marchioni or Melchioni. I have followed Sandro Pasqual, who calls him Don Nicola Amati. I assume this is how he would be addressed in Italian and how he appears in the Bologna archive.

A view of Bologna’s old town today. As a university town, it was well served with clergy in the 17th century

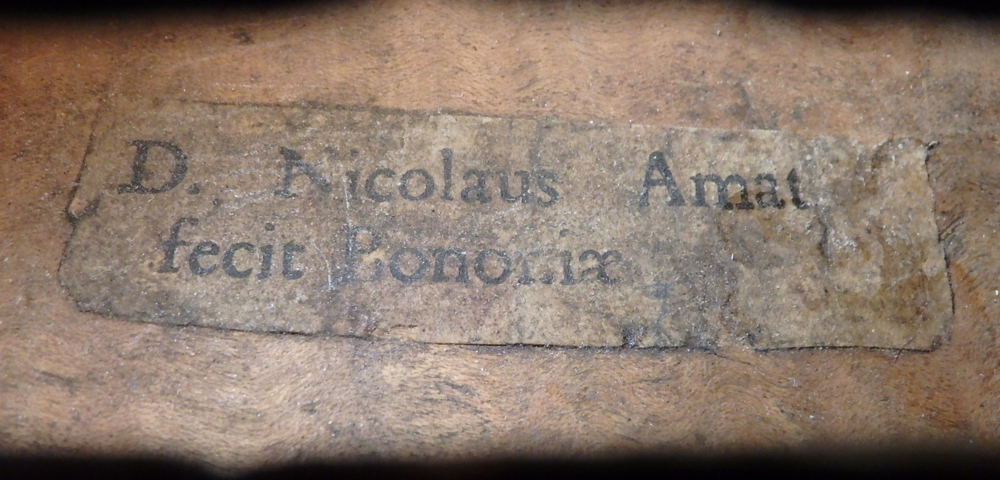

In a useful and important book published in 1998, Sandro Pasqual and Roberto Regazzi gave us the solution to a strange conundrum in violin making history. [1] We are familiar with Andrea Amati and his celebrated family – sons Antonio and Girolamo, grandson Nicolo and great-grandson Girolamo II – which became the founding dynasty of virtuoso Cremonese lutherie. But who was this ‘Dom Nicolo Amati’ in Bologna? What relation could he be? How did he find his way there from Cremona? Adding to the confusion is the wide range of styles that Dom Nicolo Amati seems to exhibit. Despite a relatively modest surviving output, his work shows distinctive yet inconsistent mannerisms that are quite hard to decipher. Among the instruments that can be confidently attributed to him are a handful of small-sized violins and at least one contralto viola and a cello; quite a typical production for a professional luthier of his time, but Dom Nicolo Amati was by no means a typical violin maker.

René Vannes speculated that he was the son of Girolamo II and considered him an amateur maker, [2] while Walter Hamma stated in the 1993 edition of Meister Italienischer Geigenbaukunst that he had no connection with the Cremonese family. [3] Henley’s Universal Dictionary lists another ten Amatis, from ‘Luigi’ to ‘Taronimus Amati of Absam’, who I think may no longer be of any concern to us, but he does describe Dom Nicolo Amati as a priest, not related to the Cremonese Amatis. [4]

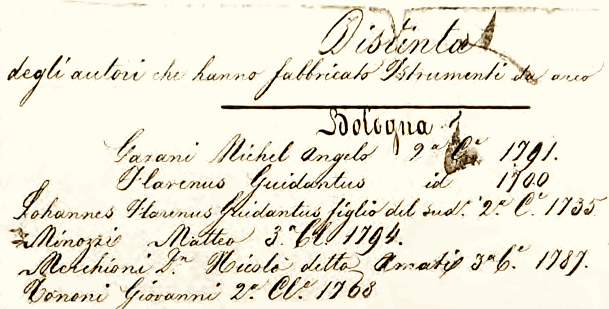

This entry from Stefano Scarampella’s 1863 notebook on the makers of Bologna provided the first link between ‘Dom Nicolo Amati’ and Nicola Marchioni – Scarampella had presumably seen an original inscription in which Don Nicola showed his real name. Document courtesy Roberto Regazzi

Sandro Pasqual’s assiduous work in the Bolognese archives finally provided the true identity of this enigmatic maker, whose real name was Nicola Marchioni. The family, whose name is also spelled variously as Melchioni or Merchioni, was apparently comfortably established in the district of Castelnuovo and Lizzano in the Emilia-Romagna, some 50 kilometres south west of Bologna itself. Nicola was born in 1662 and entered the priesthood in 1687, from which point he would have been addressed as ‘Don’, a title given to priests in Italy derived from the Latin ‘dominus’. ‘Dom’, as is often seen, is the variation found in Spanish and Portuguese.

Pasqual points out that Bologna was well served with clergy: as a university town it placed great importance on education, which for the most part was theological. Many artisans in the city were trained priests, it seems. Pasqual states that Don Nicola expressed a vocation for the priesthood, and his father provided him with an endowment to enable him to pursue his ordination. By 1715 he was living in the parish of of SS Cosma e Damiano in the eastern part of the city center with his mother and widowed sister.

Bologna was well served with clergy… [and] many artisans in the city were trained priests

It is not known when he began making violins or when he adopted the pseudonym ‘Amati’, but it is clearly a homage to the Cremonese makers and was presumably intended to mark a distinction between his two parallel occupations of priest and violin maker. His brother Sebastiano lived close by, and Pasqual suggests that they worked together in violin making, with Sebastiano’s sons (Don Nicola’s nephews) Giuseppe and Gaetano assisting later. There seems to be no other evidence to support this, but Don Nicola did make Giuseppe and Gaetano his heirs. Unfortunately they both predeceased him and the legacy eventually went to another nephew, Girolamo. Don Nicola outlived most of his family, retiring in 1750 to live with Girolamo in Vergato, a village 40 km southwest of Bologna. He died in about 1752, aged 89.

Tracing Don Nicola Amati’s origins in violin making is still not straightforward, however. The dominant lutherie family in the city had been the Tononis, originating with Gaspare Tononi who lived from 1607 to 1693, but who is recorded only as a ‘case-maker’. His son Giovanni (1640–1713) was, however, a highly accomplished violin maker with a clearly classical style. Stringed instrument making in Bologna developed, as in many other Italian cities, under the primary influence of lute makers of Germanic origin, notably the great Hans Frei. The Frei family turned the via San Mamolo into the instrument making quarter in the middle of the 16th century, and Antonio and Girolamo Brensi are the first recorded bowed instrument makers there, beginning in the 1560s. Another family of lute makers, the Pfanzelts of Füssen, arrived in the district in the 1630s and were joined not long after by another Füssen native, Martino Otti. Gaspare Tononi must have been involved with these activities. Otti we do know was a violin maker; the inventory of the Marquis of Carbonelli [5] from 1740 lists a violin by Otti ‘repaired by Antonio Stradivari in 1723’, and one other surviving example has many hallmarks of Bolognese violin making already in place. Otti died in Bologna in 1703, and it seems more than likely that he would have been young Giovanni Tononi’s prime informant as a violin maker.

There was another Bolognese family involved in violin making in via San Mamolo at around this time, the Guidanti; Floriano Guidanti (c. 1643–1715) was employed as an instrument repairer by the Accademia Filarmonica from about 1660 and his position was inherited by his son Giovanni (1687–1760). The later Bolognese maker G.A. Marchi singled out Floriano alone among his Bolognese predecessors in his ‘manoscritto Liutario’ of 1786, citing him alongside Stradivari as having determined certain correct proportions. [6] Giovanni was a sophisticated maker, working in a very Amatese style with a distinctive pale, clear golden varnish. But the working styles of the Tononi and Guidanti do not seem to overlap consistently, whereas there are strong lines of development traceable from what little is known of Otti, through Giovanni Tononi and finally leading to Don Nicola.

There are strong lines of development traceable from what little is known of Otti, through Giovanni Tononi and finally leading to Don Nicola Amati

When Giovanni Tononi died in 1715, Don Nicola was just embarking on his violin making career – at least no instruments of his are reliably dated prior to this year, in which he moved permanently to his parish in SS Cosma e Damiano, just a little to the east of the via San Mamolo. Another actor in this scene was Giovanni Tononi’s son Carlo. Born in 1675, Carlo was significantly younger than Don Nicola and it is a little hard to imagine him as Don Nicola’s teacher. Moreover, Carlo’s activity in Bologna seems to have been at least partially taken up with repair work, as violins made by him are far rarer than those he made in Venice after his departure for that city in 1717.

At that time Giovanni Guidanti would have been the senior maker in the city and the most sophisticated. Michel Angelo Garani (c.1665–1743) was also a fine maker who closely followed the style of Giovanni Tononi, but his work is very rare and he also seems to have been active in the church, employed as the verger of S. Cristina della Fondazza, located just a few streets south of Don Nicola’s church. Nevertheless it seems impossible for Don Nicola to have been taught by anyone other than Giovanni Tononi, and his somewhat capricious style seems to evolve naturally, if idiosyncratically, from that starting point.

Bolognese makers share a few characteristics. A preference for beech wood in the purfling is one; the setting of the locating pins in the back well within the purfling boundary is another. But other traits are hard to determine. With Don Nicola we see all the variables exhibited by his peers, but a few defining traits.

His outline model is very much his own, most distinctive perhaps because of the tightly turned lower corners

His outline model is very much his own, most distinctive perhaps because of the tightly turned lower corners. The center bouts are generally quite long in proportion and terminate in a small inner radius at both ends, rather than the slower arc in the lower corner that we are more accustomed to seeing. The lower bouts are beautifully rounded and Amatese but are relatively diminished, with the upper bouts seeming a little wider than usual. The impression given is that these designs were carefully drawn out, following certain principles, but not those shared precisely by other makers of his circle. He used two models regularly, a larger one with a back length of around 357 mm and a smaller one of around 352 mm.

The arching is generally quite full and rounded, certainly more like that of Carlo Tononi than Giovanni, whose work can actually be quite low and flat for the period. The soundholes are set a little low on the table and exhibit a wide range of styles. The most common are quite broadly cut, set upright and parallel, with small wings. But some quite Guarnerian shapes with elongated wings, slightly axe-blade shaped and set at various angles but with only a rudimentary fluting, can be seen in later years.

A rare original label from a Don Nicola violin dated c. 1720. Photo: Tarisio

Authentic Don Nicola labels are hard to come by and are scattered roughly between 1715 and 1744, so the chronology of his style is hard to assess. Interestingly, some labels are printed in red, as are those of another Bologna alumnus, G.B. Rogeri, albeit in his time in Brescia. It may have been a conscious acknowledgement of his predecessor, in the same way that his pseudonym recognises the Cremonese Amati. Another slightly surprising feature that tends to support this picture of Don Nicola as a craftsman very well informed of his own tradition, is the blackened chamfer that appears on many of his scrolls. This of course is an innovation that has been credited to Antonio Stradivari around 1700 but was not widely adopted outside Cremona for many years, and not widely until it became general practice to make close imitations of Stradivari’s work in the 19th century.

The scrolls are generally recognisable, although they too can vary widely. What seem to be early instruments have a fairly conventional Amatese form, but he developed a very large eye to the volute and a straightened pegbox profile, usually terminating in a very sharply downturned chin. The central ridge between the flutes generally projects above the level of the edge chamfers.

The purfling, usually with a beech core and sometimes, somewhat unusually, with stained beech for the outer strips also, has other distinctive features. It looks as if Don Nicola laid the purfling into the middle bout first, with the mitre pushed to the end of the corner. The purfling from the upper and lower bouts were then fed into the joint, but more often than not fail to align fully at the points.

Don Nicola violin from c. 1732. He was one of the earliest to adopt Stradivari’s practice of blackening the chamfers of the scroll

More photosOf course, the varnish is what takes the eye first, and in Don Nicola’s case it is again the range and variety of the varnishes he used that is most striking. Giovanni Tononi used some very rich red varnish, alongside some of more Amati-like golden-brown hue, and Don Nicola likewise made use of all shades, from a deep, quite thick red that seems most common in the early period, and can be given to craquelure and other textural interest, to a softer golden layer that can also sometimes break down into quite large-scale flaking, while in some – possibly late – work it is a comparatively hard, dull and uniform red-brown. The ground is consistently reflective and gold-tinged and the overall effect unmistakably that of the definitive 18th-century Italian luthiers.

Don Nicola Amati Marchioni is a fascinating and enigmatic maker of the late classical period, but there are several ways of imagining the man at work. A romantic vision of the parish priest distracting himself from the cares and responsibilities of his parish among the wood shavings and varnish pots might well be less realistic than the image provided by Pasqual of an ambitious and entrepreneurial workman overseeing his brother Sebastiano and his nephews Giuseppe and Gaetano, thereby earning some extra income to eke out his stipend. It is one of the many fascinating histories that make up the traditions of violin making, ripe for speculation and interpretation, but what remains is a remarkable inheritance of instruments, each one clearly invested with a spark of imagination, with care and forethought in their execution, and great and lasting value.

John Dilworth is a maker, writer and expert. He has written extensively about fine instruments and their makers, and is a co-author of ‘The British Violin’, ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ and ‘The Voller Brothers’ among other books.

Notes

[1] Sandro Pasqual & Roberto Regazzi, Lutherie in Bologna: Roots & Success. Florenus Edizioni 1998.

[2] René Vannes, Dictionnaire Universel des Luthiers. Les Amis de la Musique, Bruxelles 1988.

[3] Walter Hamma, Meister Italienischer Geigenbaukunst. Florian Noetzel Verlag 1993.

[4] William Henley, Universal Dictionary of Violin and Bow Makers. Amati 1973.

[5] Carlo Chiesa & Duane Rosengard, The Stradivari Legacy. Peter Biddulph, London 1998

[6] G.A. Marchi, Il Manoscritto Liutario Bologna 1786. Ed. Roberto Regazzi, Arnaldo Forni, 1986, pp. 86 & 288.

Additional sources

Ian Woodfield, The Early History of the Viol. Cambridge University Press 1984.

Richard Bletschacher, Die Lauten- Und Geigenmacher Des Füssener Landes. Frederich Hofmesiter 1978.