For Denmark the 19th century began in horrific disarray after the confiscation of its fleet in 1801 and the bombardment of Copenhagen in 1807, as we saw in part 1. National bankruptcy followed in 1813, and the loss of Norway (which had been part of Denmark since 1536) in 1814 further diminished the country’s power and pride.

In 1809 Constanze Mozart, the widow of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, married a Danish diplomat, Georg Nicolaus Nissen, and the following year she wrote to her family in Vienna: ‘It still smells burnt here in Copenhagen’ – a reference to the 1807 bombardment and subsequent fire. Denmark suffered further in the 1864 Prussian war, after which a substantial part of southern Jutland was taken over by Germany. From 1864 Denmark had never been smaller in size, and this lasted until 1920, when part of the land was regained by democratic vote. Indeed, Shakespeare’s line from Hamlet, ‘Something is rotten in the state of Denmark,’ could never have been more appropriate.

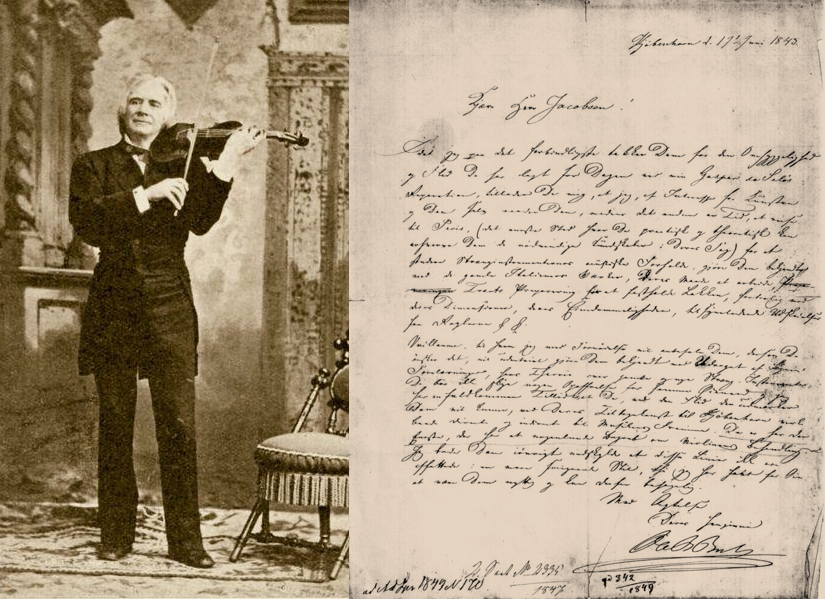

Norwegian virtuoso Ole Bull and the letter of recommendation he wrote for Thomas Jacobsen in 1842

One might suspect the Danes would fall into a severe depression. But the Romantic era swept fresh winds over the country and a new national identity began to grow. The number of artists rose dramatically during the 19th century and as Copenhagen was a small capital, it is not surprising that the many poets, composers, painters, musicians and violin makers living there all knew each other – the city was home to writers Hans Christian Andersen (1805–1875), Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855), composers Niels Wilhelm Gade (1817–1890) and Johan Peter Emilius Hartmann (1805–1900), painters Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg (1783–1853) and later Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864–1916) and Peder Severin Krøyer (1851–1909), to name just a few. Culture flourished!

One important musician who visited Denmark from around 1830 was the Norwegian violin virtuoso Ole Bull (1810–1880), the ‘Paganini of the north’, who performed many concerts there and occasionally hired claqueurs (professional applauders) to hype up the audience. Bull, who had befriended Jean Baptiste Vuillaume in Paris, became the catalyst that moved Danish violin making into a more modern direction.

On a visit to Copenhagen in 1842, Bull asked Thomas Jacobsen (1810–1853) to repair his damaged Schatzkammer-geige (the so-called Gasparo ‘da Salò’ violin, today housed in the Vestlandske Kunstindustrimuseum in Bergen, Norway, and now regarded as a copy by most experts). Bull, highly satisfied with Jacobsen’s repair, wrote a letter of recommendation to enable Jacobsen to study with Vuillaume in Paris during 1845–46. The trip was financed by a three-year grant of 300 rigsdaler per annum (equal to the annual salary of a concertmaster!) given by the Reiersen Foundation [1] and King Christian VIII.

Thomas Jacobsen violin made in Copenhagen in 1848, the year after he returned from training in J.B. Vuillaume’s Paris workshop

Jacobsen is one of the most interesting figures in Danish violin making. He was born in Jutland and apprenticed at a young age with a local carpenter, Peder Hansen Holm, who also made some violins. He then enrolled for military service and spent eight years in Copenhagen from 1833. In his spare time he apprenticed with Niels Jensen Lund at the Royal Horseguards Barracks and from 1841 worked independently as a violin maker. From 1844–1845 Jacobsen traveled through Europe, gaining experience at the best workshops, including Bausch in Leipzig, Engleder in Munich, Sprenger in Nürnberg, and both Hoffmann and Stoss in Vienna, as well as the Vuillaume workshop in Paris. He returned to Copenhagen in 1847 and was immediately appointed maker to the Royal Court.

Tragically his career ended just six years later. Clean drinking water had for many years been a problem in Copenhagen. In fact beer was more healthy to drink than water, and a law regarding school children’s health was passed in around 1850 allowing them to drink one litre of beer per day (in those days beer was much weaker!). The summer of 1853 was extremely hot and cholera spread across Europe. Altogether 4,737 citizens died of cholera in Copenhagen that year and on July 28 Jacobsen succumbed to the illness, aged 43. This cut short the life of the best-trained, most original and talented of Danish makers, whose career encompassed a mere 12 years (six years before and six years after his journey in Europe).

A Norwegian apprentice, Gulbrand Poulsen Enger (1822–1886), had studied briefly in Jacobsen’s workshop from 1852. Enger was a military musician and played tuba and percussion in Oslo’s national theater orchestra. After Jacobsen’s death he managed the workshop for a couple of years and, thanks to Jacobsen’s European connections, he was then able to study for six months in Germany and another six months with Vuillaume in Paris in 1855. This was shortly after Vuillaume had acquired the entire Luigi Tarisio collection – a treasure trove for a young violin maker to study!

Gulbrand Enger violin, Copenhagen 1870 – a copy of the 1714 ‘Yoldi-Moldenhauer’ Stradivari owned by the Royal Danish Opera Orchestra

Back in Copenhagen in 1857, Enger married Jacobsen’s widow, Ane Kirstine, became a Danish citizen and took over the workshop. He was a prolific maker and his style could be described as Scandinavian with a French flavor. He also performed major and complicated repairs on instruments, including some of those owned by the Royal Opera Orchestra and the cellist Franz Neruda (1843–1915), who had settled in Copenhagen, and sometimes even created ‘new’ instruments from parts of old ones. In his spare time he played violin and viola in Copenhagen’s chamber music society.

From Enger’s first marriage in Oslo, a son named Poul Enger had been born in 1850. He trained with his father, which can be clearly seen on the few known instruments from his hand. He was also an excellent violinist and played with the foremost chamber musicians in Copenhagen. Around 1872–73 he was living in Stockholm but after 1875 he seems to disappear completely. No further information has been found and only seven instruments by him are known today, one of which is in Copenhagen’s Musical Instrument Museum.

Hagbarth Joachim Gulbrand Enger (1860–1921), Enger’s son from his second marriage, trained in his father’s workshop from around the age of 14. He furthered his education in 1885 by working for David Bittner in Vienna and Andreas Rieger in Munich until his father’s death forced him to return in 1886. Hagbarth was a skilled violin maker, but unfortunately not successful as a businessman. He went bankrupt in 1896 and ironically found a job at the Danish National Bank, counting money. He devoted some time to gathering information about historical Danish violin makers and these Notes on Danish Violin Making are kept today at Copenhagen’s Musical Instrument Museum.

Lars Christian Henric Larsen (1804–1866) worked outside Copenhagen, in Odense on the island Fyn. From around 1840 he produced over 200 violins, violas and a few cellos, with rather flat archings and usually a dark-brown varnish. His instruments are branded ‘C-Larsen’ with the year and a serial number. Larsen also produced silver-wound gut strings, but is no relation to today’s Larsen Strings. Reportedly he died of grief after his eldest son Carl (who had been destined to be a violin maker) died from wounds after the 1864 Prussian war. Two younger sons, Wilhelm and Christian, took over the Larsen business. They sometimes imported factory instruments from Germany and used the same numbering system as that of their father.

A violin from 1893 by Emil Theodor Hjorth, who made good use of his studies in Vienna and Paris. Photos: Tarisio

Johannes Hjorth, who apparently never studied abroad himself, must have seen the growing success of the Jacobsen–Enger workshop from 1845–60. He took this situation seriously and ensured that his son Emil Theodor Hjorth (1840–1920) was trained thoroughly in the family workshop and then from 1863–65 gained further experience first with Gabriel Lemböck in Vienna and subsequently with Bernardel père in Paris. His travels were financed by the Reiersen Foundation and the young maker also received recommendations from concertmaster Holger Simon Paulii, composer Niels Gade and Carl Mettus Weis (of whom see more below). This experience strongly influenced Emil’s craftmanship and his instruments show stylistic elements from both Vienna and Paris.

Emil Hjorth made fine, strong instruments, which at their best have a glorious oil varnish of almost Venetian quality on a golden ground. He traveled through Europe in 1891, visiting Berlin, Markneukirchen, Nürnberg, Munich, Salzburg, Vienna and Prague, and brought many fine old instruments back to Denmark; his European connections also helped set the Hjorth firm on a more international level of dealership. From 1905 his sons Otto and Knud joined the firm, which was thereafter named Emil Hjorth & Sons. Emil retired in 1906 with the future of the family business secure in their hands.

Carl Mettus Weis (1809–1872) must be mentioned despite being an amateur. A true polymath, he studied law and became head of Denmark’s ministry of culture and church matters, thus becoming responsible for many cultural events. In his spare time he played string quartets with his three brothers and studied violin making with his friend Emil Hjorth, who at times found Weis a bit intense – according to the Hjorth family, he would spend hours simply watching Emil working! However, any aspiring violin maker had to be on good terms with Weis, since he was on the board of directors of several important organisations, including the Reiersen Foundation and the Royal Opera, and a recommendation from him usually resulted in grants for young violin makers to study abroad. In 1861 he published a short book about violin making. [2] His brother Andreas Weis (1815–1889) was likewise an avid amateur maker.

After the two Weis brothers’ death, a large quantity of spare materials (half-finished tops, backs etc) were given to Emil Hjorth, who finished them by making new rib-structures and scrolls and varnishing them, creating some very interesting instruments. These are usually signed ‘C Weis fecit – E. Hjorth correxit’ and date from around 1880 onwards.

Niels Larsen Winther (1814–1880) was an enigmatic and multi-talented maker who lived in a village named Igelsø near Holbæk; he worked as a locksmith, gun-maker, clock maker and wood turner, as well as making clarinets and quite a few violins, violas and some cellos – always on the same mould and consistent in quality. Stylistically, one would assume that he studied with Niels Jensen Lund at the Horse Guards Barracks in Copenhagen, but to do so he would have had to enroll for military service, which he never did because a swollen testicle disqualified him from the army. He composed several polkas and hopsas in the folk music style, which are still played today. His instruments are usually made from plain Danish maple and branded ‘N. Winther’ (no number or year indicated) inside on the back.

Frederik Wilhelm Hansen (1829–1889) is a somewhat mysterious maker in the sense that it has not been possible to prove where he learned his craft – and yet he is one of the most original and talented of Danish makers. He was born in Christianshavn, Copenhagen, in 1829, the second son of Hans Peder Hansen, a carpenter who also made violins. Around 1855 Copenhagen was home to violin makers including Enger, Hjorth, Weis, Lund and Hans Christian Hansen (an elder brother of Frederik) and was perhaps over crowded. In 1859 Frederik sought other possibilities by moving to Randers in Jutland, which at this time was the largest city outside Copenhagen.

Scroll of an 1880 violin by Frederik Wilhelm Hansen, whose instruments are similar to those of Jacobsen and Enger. In the corner block detail the linings overlap the corner block itself – this typical detail is also seen in Peter Petersen Adamsen violins

Hansen’s instruments are very similar in style and workmanship to those of Thomas Jacobsen and Gulbrand Enger and a working connection between them is more than likely. Together with his wife, Julie Jørgensine Amalie Hansen, he had nine children of whom only two lived beyond their 27th year as a result of tuberculosis. This was a common disease among the poorer parts of society and an indicator that Hansen, despite his talent, was living in very modest conditions. Hansen’s violins have been used in our time by the jazz violinist Svend Asmussen (who celebrated his 100th birthday in February!) and violinist–entertainer Anker Buch.

Together all these craftsmen created a golden era of Danish violin making. Next we will discover how modern times shaped the fate and fame of the country’s violin making tradition.

Maker and expert Jens Stenz has extensively researched the history of violin making in Denmark and owns a large collection of Danish instruments. In part 3, he surveys the development of the country’s 20th-century makers.

Instrument photos courtesy of Jens Stenz unless otherwise marked.

Notes

[1] This fund, which still exists today, was set up in 1796 upon the death of Niels Lunde Reiersen, who left his fortune to help promote the Danish manufacturing industry.

[2] Om Violiner og deres Bygning (Violins and their Structure), published in Copenhagen, 1861.