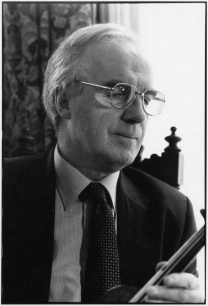

Charles Beare died on Saturday aged eighty-seven. The director of J. & A. Beare and later Beare Violins Ltd, he dedicated his life to studying the work of the great violin makers. His opinion was sought on many thousands of fine instruments and his certificates were regarded by many as an irreproachable guarantee of authenticity. Many of the world’s finest musicians entrusted him with their instruments, including Jacqueline du Pré, Yehudi Menuhin, Isaac Stern, Itzhak Perlman, Pinchas Zukerman, Mstislav Rostropovich and Yo-Yo Ma.

Charles was born in 1937. His step-father was William Beare, then director of the J. & A. Beare firm, and the young Charles began studying violin making in Mittenwald in 1958. In 1960 his step-father sent him to New York to work at the Rembert Wurlitzer firm. In his sixteen months there, he managed to study 110 Stradivari instruments and fifty-seven Guarneris. It was Wurlitzer who taught him the ‘philosophy of how to look at instruments and how to behave in the fairly rough world of violin dealing,’ as he recalled in 2004. He often paid tribute to the generosity of both Wurlitzer and restorer Simone Sacconi in sharing their knowledge with him. Throughout his life, Charles was similarly generous, sharing his own knowledge with future generations of experts and makers.

Charles’s leadership and expertise grew the family firm to become arguably the most respected dealership in the world. Upon leaving the firm in 2012, he began working with his two sons, Peter and Freddie, under the company name of Beare Violins Ltd. As the organizer of the seminal 1987 exhibition of Stradivari’s work in Cremona, Charles set out to put on public view the very best examples of each period of Stradivari’s life, and described the resulting exhibition as ‘a dream come true’. In 2013, he created another landmark Stradivari exhibition at the Ashmolean museum in Oxford. Throughout his career, he dedicated considerable efforts to researching the lives of the Venetian makers after picking up the project in 1966 after the death of his friend, Paul Rosenbaum. His research remains unpublished to this day.

Charles was a former president of the Entente Internationale des Maîtres Luthiers et Archetiers d’Art, an honorary fellow of London’s Royal Academy of Music and a frequent lecturer for the American Federation of Violin and Bow Makers and the Violin Society of America. He was made an honorary citizen of Cremona and in 2004 he received an OBE for services to the music industry.

My first interaction with Charles was in Cremona in 1996. I was a first-year violin making student – a complete nobody – and he was the biggest, larger-than-life celebrity that I knew of in the business. We bumped into each other at the entrance to Palazzo Fodri and I think I said something stupid like, “Oh my gosh, you’re Charles Beare.” He responded by asking me who I was and what I was doing there and asked me to come see him in London, as if we were old friends.

I took him up on that and visited the Wardour street shop several months later with a violin I had just finished. I can only imagine how many thousands of aspiring young makers have brought a violin for Charles’s opinion, and yet, he gave me nearly an hour of his time, critiquing and complimenting (actually, mostly just critiquing) my humble efforts. And then he showed me a dozen fiddles from the vault. What care, what generosity, what a supremely kind human being…

Charles was a careful expert, who balanced instinct with analysis and who welcomed new information and technology to support the evolution of expertise.

Charles was a careful expert, who balanced instinct with analysis and who welcomed new information and technology to support the evolution of expertise. After initially being suspicious of dendrochronology, he later embraced it and championed its use to add scientific corroboration to attributions. My colleague Carlo Chiesa remembers Charles’s rigorous dedication to archival research, ‘Charles was a tireless supporter of research because it allows us to understand a maker’s instruments in perspective and to support our hypotheses with facts. Charles was generous and believed in sharing knowledge and experience.’

In 2011, the day before the sale of the ‘Lady Blunt’ Stradivari, Charles said something to me that has influenced me greatly. He had asked me to bring the violin over so he could see it again. After talking about the violin, Charles looked at me and said – and I’m paraphrasing – ‘you know, you really should be worried about two things tomorrow: one is that this violin sells for too little; and the second is that it sells for too much.’ At the time I didn’t understand what he was saying: of course I was worried it would undersell, but why should I be worried that it would sell for too much? Only later did I realize that Charles was talking about playing the long-game to preserve the sustainability of a world that he loved dearly.

Charles’s expertise moved the world a giant leap forward. His humanity and care for this business will be remembered forever. His sons, Peter and Freddie continue the family tradition of excellence.

![]()