In 1733 Cremona was home to three master violin makers: Antonio Stradivari, Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ and Carlo Bergonzi. The Stradivari workshop was by then world-famous and Guarneri was the third generation in a family of successful makers, but Bergonzi was the first in his family to take up the craft. He had no famous parentage or pedigree, and yet in around 1730, he burst onto the scene with his sensational, masterpiece violins. The label of the 1733 ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ gives evidence of a maker who wasn’t afraid to be different and who did things with confidence and determination.

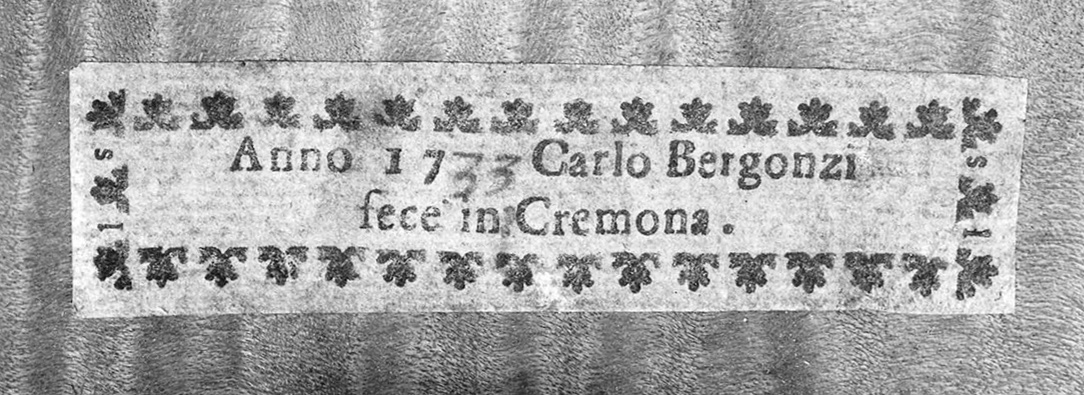

The original label of the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’. The syntax is unusual; there’s no mention of Bergonzi’s training or background and details of the typography raise interesting questions.

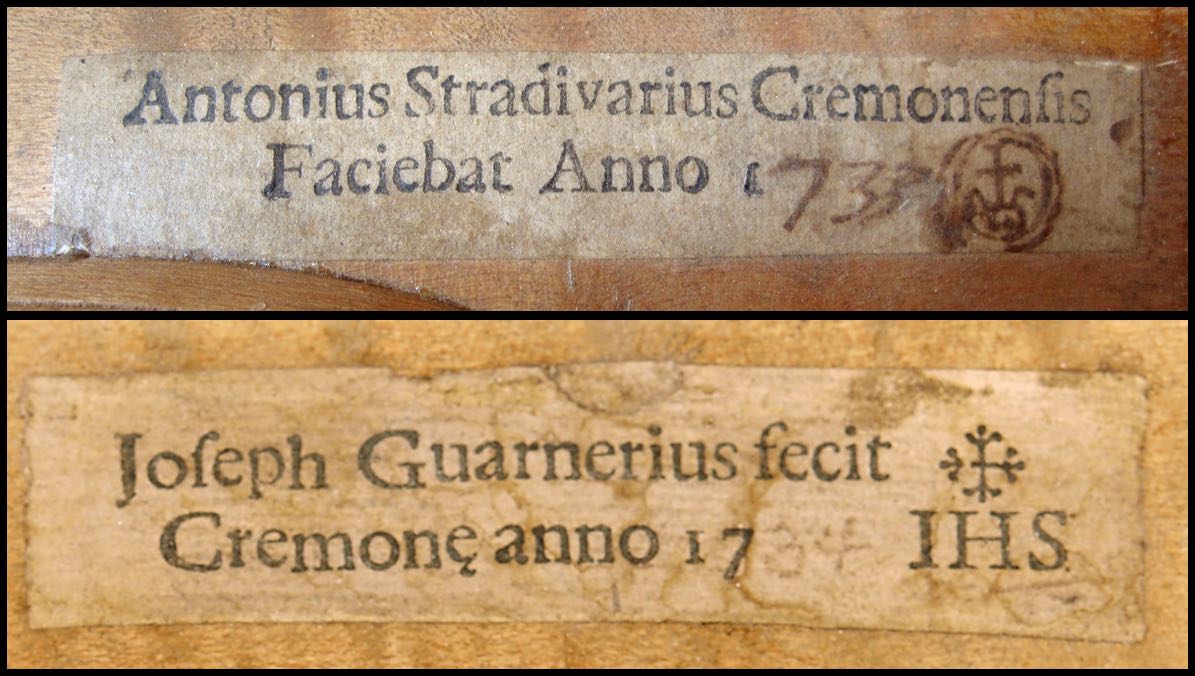

Usually labels begin with the maker’s name: for example, “Antonius Stradivarius Cremonenfis Faciebat Anno 17__.” All the Cremonese families before Bergonzi had composed their labels this way and, in fact, few makers anywhere broke with this convention until the 20th century. But for some reason, Bergonzi started his labels with the date: “Anno 17__ Carlo Bergonzi fece in Cremona.”[1]

…he could have used this opportunity to assert his pedigree and bolster his bonafides perhaps by telling us something about his training.

The text of Bergonzi’s label is notably short. Being the first of his family to work in the trade, he had no reason to name his father, brother, uncle or grandfather as the second and third generations of the Amati and Guarneri families did. Still, he could have used this opportunity to assert his pedigree and bolster his bonafides perhaps by telling us something about his training. It was common practice in the 17th and 18th centuries that first-generation makers named their teacher on their labels. Andrea Guarneri, G. B. Rogeri, Bartolomeo Pasta and Giacomo Gennaro all identified themselves on their labels as alumni of Nicolo Amati. Why didn’t Bergonzi tell us who his teacher was?

The first Bergonzi labels appear in instruments made when the maker was already in his late forties. Perhaps by this point he was well established and didn’t need to name-check his master as a younger maker would do. Or maybe, as recent expertise suggests, his training wasn’t so straightforward. Although it has yet to be confirmed, the consensus among experts and scholars is that Bergonzi trained first in the Vincenzo Rugeri workshop and then, after Rugeri died in 1719, he spent the next decade making some instruments independently while simultaneously doing work for Stradivari. What we do know is that in around 1732, his production increased. Bergonzi turned fifty in the year the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ was made. He was creating masterpieces that rivaled the best makers in town and had no reason to tell us who his teacher was.

Bergonzi turned fifty in the year the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ was made. He was creating masterpieces that rivaled the best makers in town and had no reason to tell us who his teacher was.

As John Becker points out in his essay in the catalog to the 2010 exhibition Carlo Bergonzi: A Cremonese Master Unveiled, Bergonzi was the first Cremonese maker to use a label with a decorative border. What was his inspiration? Perhaps he had seen the labels of his Venetian contemporaries Carlo Tononi and Peter Guarneri, who both started using a label with a similar ornamented border a decade or so earlier.[2] Or perhaps his inspiration was more local. Original labels from Vincenzo Rugeri are rare and yet I am curious why so many facsimile labels of Bergonzi’s presumed teacher have a decorative border not so dissimilar to that of Bergonzi. Did Rugeri also use a label with a decorative border?

The original label in the 1733 ‘Tschudi, Martzy’. Photo: Cozio archive.

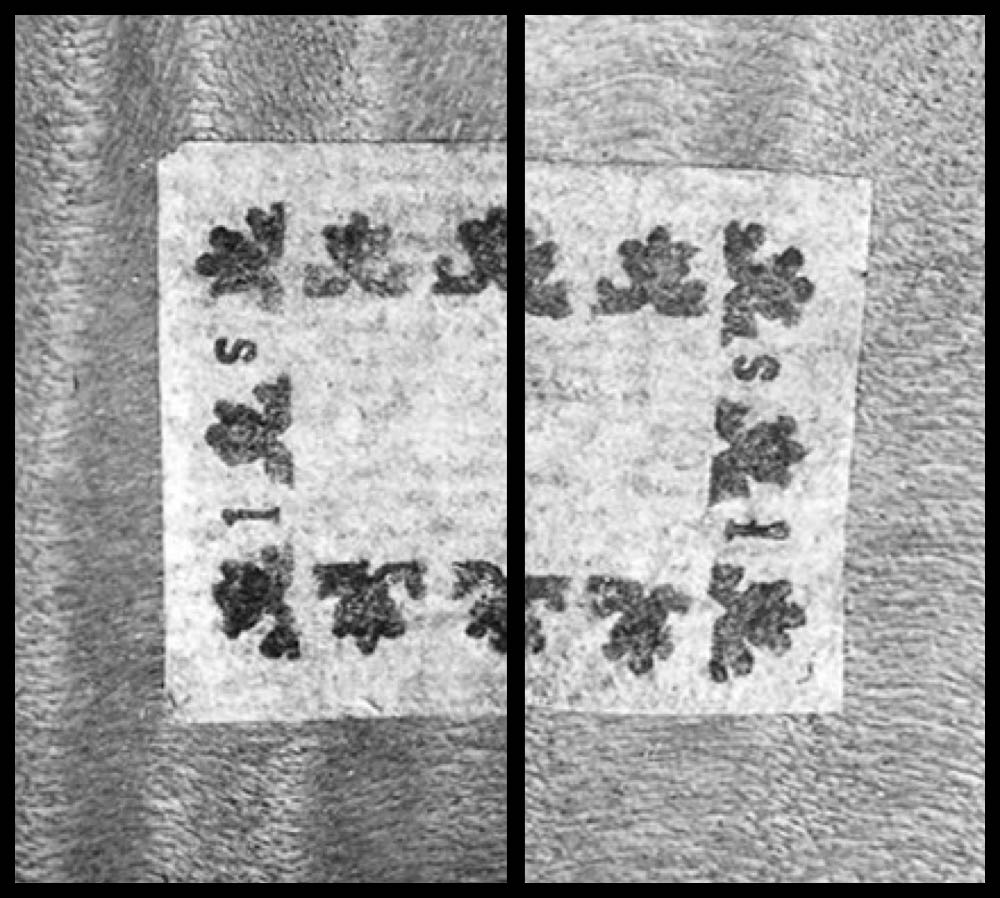

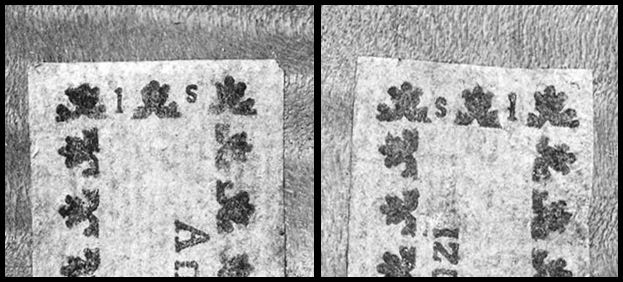

There are two known variants of Bergonzi’s labels: one he used before 1730 and the other after.[3] The text and typography are the same, but on his second label, which is the type used in the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’, Bergonzi inserted two letters between the decorative elements of the label’s border. The letters are too conspicuous to be unintentional. Their inclusion must have been deliberate, but what do they mean?

The two letters inserted into the border are too conspicuous to be unintentional. But what do they mean?

The other two master makers in Cremona at this time utilized prominent symbols on their labels: Stradivari featured a circular insignia of a cross flanked by his initials “(A†S)” and Guarneri had recently debuted his own new label design in around 1731 which included a cross printed above the letters “IHS”. These initials were a Christogram derived from the first three letters of the Greek spelling of Jesus (ΙΗΣΟΥΣ). Since the 7th century, IHS had stood for the Latin motto, Iesus Hominum Salvator (“Jesus Savior of Mankind”), and by the 17th century, it had come to represent the order of Jesuits. There have been many theories about Guarneri’s use of the IHS insignia — was it a religious devotional element? or an indication of a Jesuit connection? — but historians currently believe it was most likely a reference to a sign or emblem at the location of Guarneri’s new workshop.[4] Might Bergonzi’s letters be an “I” and an “S” and might they have had a similar purpose or significance to Guarneri’s “IHS”? Both appeared on the makers’ labels at around the same time. Did “IS” stand for an abbreviated “Iesus [Hominum] Salvator”? Or was the H of IHS overprinted with the border decoration ?

Stradivari and Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ were Bergonzi’s only local competitors in the early 1730s and they both utilized a monogram insignia on their printed labels. Shown above is a Stradivari label from the same year as the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ and a Guarneri label from the year after.

I discussed this subject on several occasions with my friend and colleague Carlo Chiesa, the violin maker, researcher and author in Milan. He suggested that perhaps the letters could be “SI” to stand for “Societas Iesu”, the Latin name for the order of Jesuits. In the 18th century, as in today, when a name was followed by the letters “S.I.” (or “S.J.”) this indicated that the person was a member of the Jesuits. Was Bergonzi alluding to a Jesuit connection?

Carlo also suggested that perhaps the second letter isn’t an “I” but rather a lower-case “L”. The relative heights of the letters would in fact indicate that the “s” is lower-case which would mean that the other letter is not an “i” but an “l”. If the letters were intended to be “sl” this could introduce new possibilities.

Was the second letter intended as an L or an I? Or was it intended as anything at all?

In 1721 Bergonzi and his family moved from the parish of San Silvestro, where the recently deceased Vincenzo Rugeri had his workshop, to a house in San Luca, slightly more north of the city center. The building that the Bergonzi family moved into was owned by a social fraternity called the Fabbrica di San Luca which was hosted by the church of San Luca.[5] Bergonzi was put forth for a leadership role in the Fabbrica in 1726 and was also active in another social fraternity based in the church of San Luca, the Compagnia del Santissimo Sacramento from 1723 to 1727.[6] Was the “sl” a semi-hidden tribute to Bergonzi’s new social alliances in the parish of San Luca?

Original labels are important. Very important. However … Let’s not discount the possibility that these letters — an “s” and an “l” (or was it an “L”?) — could be just random typography, fillers added to make space between the decorations on a craftsman’s label.

“Well,” said the printer “there isn’t room for another flower, let’s just add a squiggle and be done.” Which might have sounded something like “Cat! Gh’è mìia fioùr… Ciappaa el scarabòcc e endùm!!”

This is our last Carteggio for the year. Happy holidays and see you in 2023.

Notes:

- Several 17th and 18th century makers used a label for workshop productions which began “Sotto la disciplina.” A few chose “Fatto da…” But by far and away most labels of the period open with a name. In the 20th and 21st centuries the two significant exceptions, which begin with “Anno…,” are Giuseppe Fiorini’s labels from his Munich period and the contemporary Cremonese maker Riccardo Bergonzi (no relation).

- By the mid-18th century labels commonly had a decorative border in Venice, Florence and Mittenwald.

- John K. Becker, “Technical Analysis of the Instruments of Carlo Bergonzi” in Carlo Bergonzi: A Cremonese Master Unveiled (Cremona: Consorzio Liutai Antonio Stradivari Cremona, 2010), 71-72.

- See Carlo Chiesa and Duane Rosengard’s explanation in Peter Biddulph, The Violin Masterpieces of Guarneri del Gesù, London, 1998.

- Duane Rosengard, “An Unlikely Succession” in Carlo Bergonzi: A Cremonese Master Unveiled, (Cremona: Consorzio Liutai Antonio Stradivari Cremona, 2010), p. 39.

- Ibid, p. 41.