This dazzling Bergonzi once belonged to the highly esteemed but relatively unknown Hungarian violinist Johanna Martzy. In Part One of a two-part Carteggio, Tarisio’s Founder, Director and Expert Jason Price traces the story of the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ whose provenance leads back to the maker himself.

In 1776 Count Cozio di Salabue, the first important collector of Cremonese instruments, bought five “intact” Carlo Bergonzi violins from the maker’s son-in-law, Giovanni Batista Cabrinetti. From Cozio’s notes and the provenance of the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ we can deduce that it was one of these instruments.[1]

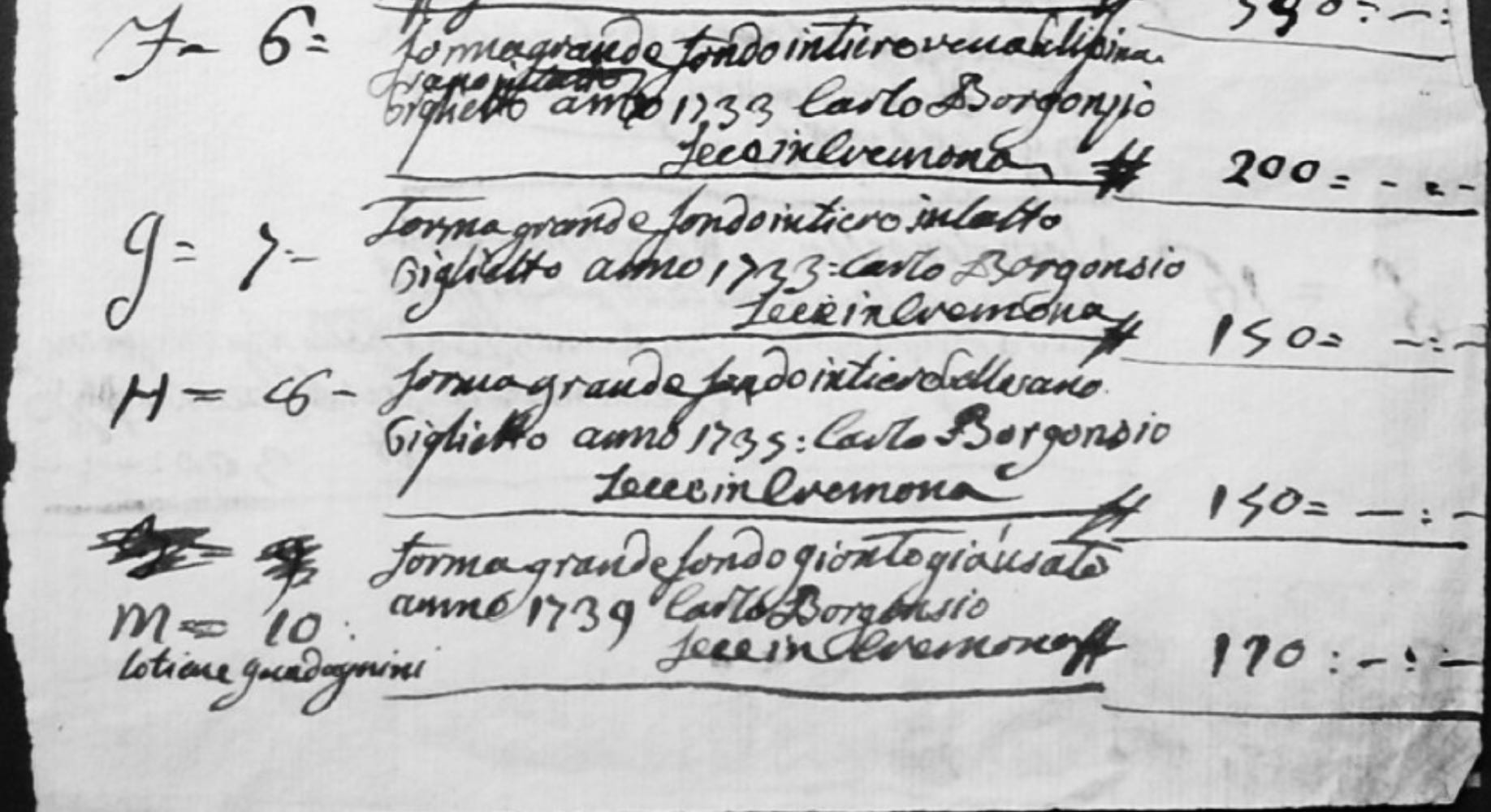

Cozio’s inventory of June 21, 1778 (Cozio MS 49). Both 1733 Bergonzi violins are described as “Forma grande, fondo intiero … intatto” (large model, one-piece back, mint condition).

But why was Bergonzi’s son-in-law in possession of five apparently unused Bergonzi violins nearly thirty years after the maker’s death? As my colleague Duane Rosengard explains in his essay to the catalog to the 2010 exhibition Carlo Bergonzi: A Cremonese Master Unveiled, the connections between the Cabrinetti and Bergonzi families were numerous and significant: Antonio Cabrinetti (Giovanni Battista’s brother) was Bergonzi’s landlord from 1725 until around 1745; Bergonzi’s brother Pietro was a witness at Antonio Cabrinetti’s marriage; Antonio Cabrinetti served as godfather to Pietro’s daughter; and finally, Giovanni Batista Cabrinetti married Bergonzi’s daughter Gertrude in 1747 just seven months after the maker died.[2]

A transaction unearthed by Rosengard illustrates a further, possible hereditary route by which these five Bergonzi instruments could have come into Cabrinetti’s possession. In 1764 G. B. Cabrinetti settled a disagreement with his nephew Pietro by accepting twelve violins and six paintings.[3] The violins are not described, but quite likely they included the five Bergonzi violins that Cabrinetti would sell to Cozio twelve years later.[4]

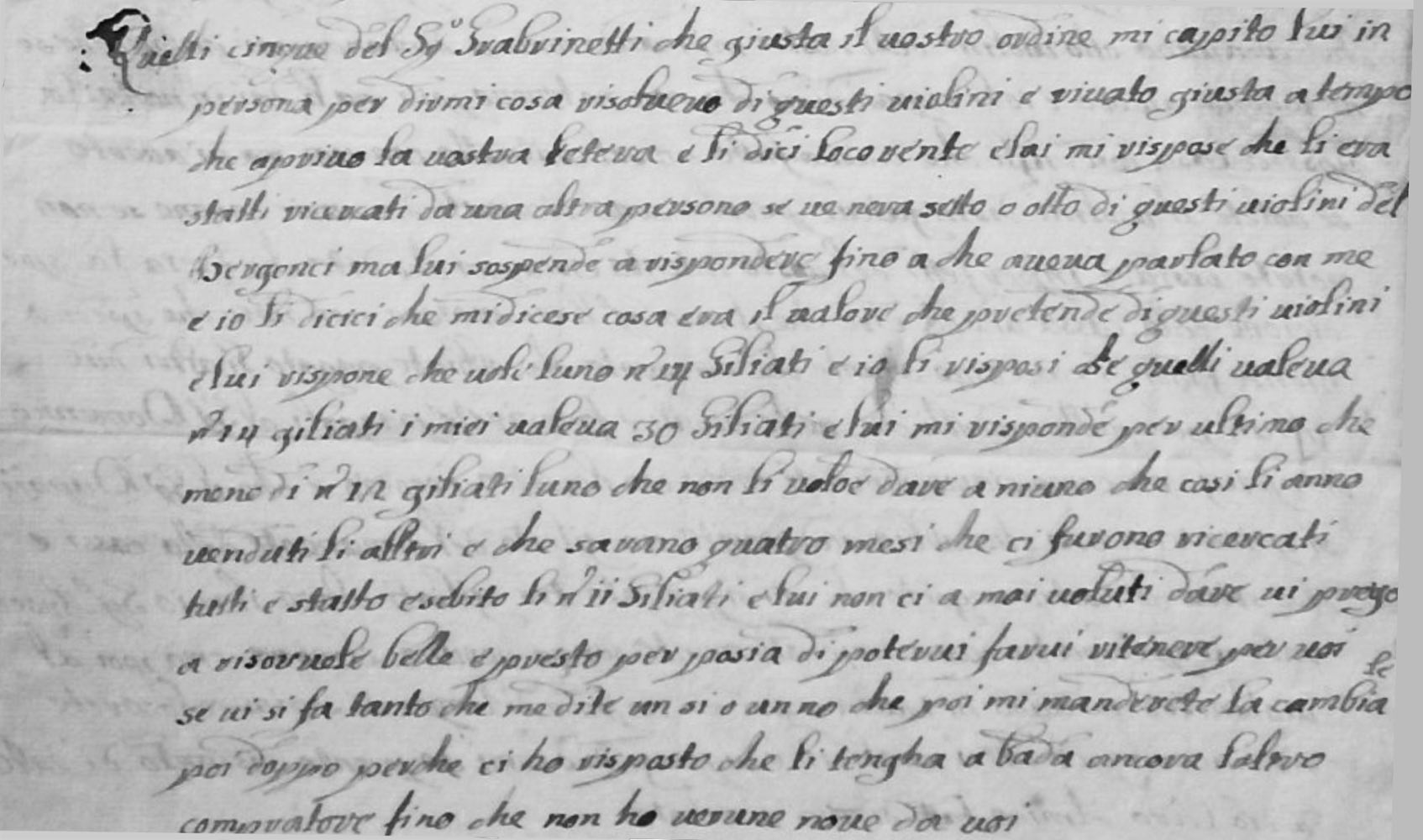

A letter from Antonio II Stradivari to Cozio’s agent negotiating the purchase of the five Bergonzi violins from Cabrinetti. The letter begins “Questi cinque del Sig Cabrinetti…” (these five [violins] from Sig. Cabrinetti) and goes on to say that someone else was interested in “sette o otto di questi violini di Bergonzi” (seven or eight of these Bergonzi violins).

The Count was pleased with his acquisition and dedicated many entries in his notebooks to the instruments, referring to one 1733 violin in particular as “‘mio più grande e bel violino del Carlo Bergonzi” (my largest and most beautiful Bergonzi).[5] The ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ remained in the possession of Count Cozio for over four decades until it was acquired by the violin dealer and collector Luigi Tarisio. Cozio and Tarisio met several times between 1827 and the Count’s death in 1840, and it is likely that during one of these encounters, Tarisio acquired the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’.[6]

Count Cozio referred to one 1733 violin in particular as “‘mio più grande e bel violino del Carlo Bergonzi” (my largest and most beautiful Bergonzi)

When Tarisio died in 1854 the Parisian dealer Jean Baptiste Vuillaume quickly acquired the entirety of his collection for a total of 80,000 francs.[7] According to legend, while most of Tarisio’s instruments were in his apartment in Milan at the time of his death, six of the best instruments were found in a farmhouse in the village of Fontanetto in the province of Novara. These were reported to include the 1742 ‘Alard’ Guarneri, the 1716 ‘Messiah’ Stradivari and the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’. Having just made what was quite possibly the best acquisition of his life, Vuillaume swiftly whisked the windfall collection away to Paris.

Some time later Vuillaume sold the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ to Hugo Wehrle (1847–1919), a German violinist from Stuttgart who had studied first with Ferdinand David and later with Vuillaume’s son-in-law, Jean Delphin Alard. Wehrle was under Alard’s tutelage in around 1860 which is probably when he acquired the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ from his teacher’s father-in-law.

The Zajic String Quartet in Hamburg in c. 1890: from left: Michael Löwenberg, Florian Zajic, Julius Schloming and Albert Gowa. With its deep ribs and seemingly full varnish, could this be the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ pictured with Schloming?

From Wehrle the violin passed to Julius Schloming, a violinist from Hamburg who was a concertmaster and the second violinist in Florian Zajic’s string quartet. In 1904 the violin was sold to Baron Alfred von Liebieg through the Viennese violin maker and dealer Carl Hermann Voigt. Baron Liebieg had made his fortune in sugar manufacturing and served as the German Consul General in Vienna. In addition to the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ the Baron owned two 1704 Stradivari violins and the c. 1727 ‘Lenau’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’.

The English dealers, W. E. Hill & Sons knew of the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ from when it was still in the possession of Wehrle. They had tried to buy it in around 1890, presumably before Schloming made his purchase.[8] Arthur Hill called it “one of the finest Bergonzi’s in existence”[9] and placed it among the “four finest examples of Bergonzi’s work known to us.”[10] The Hills also provide an interesting clue as to the transfer of the violin after Baron Liebieg died in 1930. In 1934, Arthur Hill writes that “[the American dealer and collector] Nathan Posner has returned from the Continent where he does not appear to have had much success in as much as the ‘Wehrle’ Bergonzi, the property of the late Baron Leibig [sic], has slipped through his fingers.”[11]

Arthur Hill called it “one of the finest Bergonzi’s in existence” and placed it among the “four finest examples of Bergonzi’s work.”

Baron Liebieg had done business with several dealers, and the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ was highly sought after, but it was Albert Caressa in Paris who eventually acquired the instrument in around 1935. In 1936, the violin was sold by Hug & Co. in Zurich to Daniel Tschudi, an amateur violinist and the heir to a publishing house in Glarus, Switzerland. Records from the Hug firm show that the violin was purchased from Caressa and sold to Tschudi for 44,000 Swiss francs.[12] Although just twenty-eight when he bought the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’, Tschudi had already developed a keen eye and an appreciation for fine instruments. In 1942 he published a small monograph on his prized Bergonzi which was limited to 150 copies.

In 1949 Tschudi invited the Hungarian violinist Johanna Martzy to give a concert in Glarus through the local concert and performance society of which Tschudi was an organizer. Afterwards, Tschudi showed Martzy his Bergonzi and a Peter Guarneri of Venice which he had bought four years earlier from the widow of Carl Flesch. Tschudi must have been impressed by Martzy’s playing because shortly after their meeting, he asked her if she wanted to borrow his treasured Bergonzi.[13]

Martzy recorded the Dvorak concerto for Deutsche Gramophone in 1953 in Berlin with Ferenc Fricsay and the RIAS-Symphonie-Orchester.

Martzy was born in 1924 in Transylvania. As a small child she had played for violinist Jenö Hubay in Budapest and later entered the Budapest Academy of Music.[14] In 1943 she debuted with the Budapest Philharmonic under Willem Mengelberg but fled Hungary after the Nazi occupation a year late. In 1947, Martzy won the top prize in the Geneva Competition[15] and from then her career took off. In the 1950s she toured widely through Europe and debuted in America in 1957, playing with the New York Philharmonic first in November and then again in December the following year.[16]

In 1954 she moved from Deutche Gramophone to Colombia in 1954. She recorded the Brahms concerto with the Philharmonia Orchestra and Paul Kletzki in 1954

Martzy’s playing attracted critical acclaim and yet her reputation as a leading violinist never fully took root. This was partly the result of the war, which interrupted her career at its formative stage, but also due to her own retreat from concertizing after her daughter Sabina was born in 1960. In an article in the The American Scholar, Sudip Bose makes the case that Martzy was “caught between eras,” and that the transition to stereophonic recording made record labels like Deutsche Grammophon drop her earlier unfashionable monophonic recordings from their active catalogs even as she was at the height of her career.[17]

The Canadian pianist Glenn Gould was one of the artists who recognized Martzy’s talent during her lifetime and called her “the most underrated of the great violinists of our age.”

Tschudi and Martzy died within a year of each other in tragic and unexpected circumstances: Tschudi was struck by an automobile while crossing the road,[18] and Martzy died of cancer in 1979. In recent years, Martzy’s recordings have achieved cult status among audiophiles. Ironically, her monophonic recordings which had previously been dropped by her label now sell for huge sums online. The Canadian pianist Glenn Gould was one of the artists who recognized Martzy’s talent during her lifetime and called her “the most underrated of the great violinists of our age.”[19]

Johanna Martzy in c. 1947 at around the time she won the top prize in the Geneva Competition

After Martzy’s death, her daughter Sabina sold the instrument through the dealer Pierre Gerber to a Swiss foundation. In 1992, the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ was sold to a collector in Japan who owned it until 2011.

The ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ is featured in several important publications including the catalog to the 2010 exhibition Carlo Bergonzi: A Cremonese Master Unveiled; a monograph written by Eric Blot in 2003; the monograph published by Daniel Tschudi; and in Walter Hamma’s Meister Italienischer Geigenbaukunst.

Next week, in Part Two Jason Price discusses an unexplained mystery of the ‘Tschudi, Martzy’ label.

Notes:

- Inventories of 1777, 1778, 1779, 1801 (Cozio MS 37, 49, 39, 42, 43) The Carteggio of Count Cozio, Cremona, Biblioteca Statale.

- Duane Rosengard, “An Unlikely Succession” in Carlo Bergonzi: A Cremonese Master Unveiled, (Cremona: Consorzio Liutai Antonio Stradivari Cremona, 2010), 44-46.

- Ibid, p. 45.

- In fact, a letter dated June 30 1776 from Antonio (II) Stradivari to Cozio’s agent Anselmi indicates that originally there were more than five Bergonzi instruments in Cabrinetti’s possession.

- The Carteggio of Count Cozio, Cremona, Biblioteca Statale. May 30, 1816.

- The two 1733 Bergonzi violins are not mentioned in Cozio’s surviving documents after 1816 and neither instrument is included in the inventory of instruments sold by Cozio’s daughter Matilde to Tarisio in 1840. See Eric Blot, Carlo Bergonzi Violin 1733 (Cremona, Eric Blot Edizioni, 2003).

- Roger Millant, J. B. Vuillaume, Sa Vie et son Oeuvre (London, W. E. Hill & Sons, 1972), 124-125.

- W. E. Hill & Sons Business Records, unpublished, November 14, 1910.

- Ibid, October 25, 1912.

- Ibid, December 22, 1916. On December 23, 1916 the Hills gave a contradictory account of the “Wehrle”’s provenance, that Laurie acquired it from N. F. Vuillaume who acquired it from Tarisio. This is possibly a confusion with the ‘Bennett, Reifenberg, Brooks’ 42387.

- Ibid, June 24, 1934.

- Invoice of November 14 1936. Sale and inventory records courtesy of Martin Haupt of Hug & Co.

- Glenn Armstrong, Coup d’Archet, 1997, https://www.coupdarchet.com/catalogue/product/11-coup-003-johanna-martzy.h’Tschudi, Martzy’l

- https://theamericanscholar.org/the-cult-of-johanna-martzy/

- The Jury awarded Martzy the second prize unanimously, a first prize was not given that year. www.concoursgeneve.ch

- https://archives.nyphil.org/index.php/artifact/b900951f-3e46-4624-9a99-6f0243937385-0.1/fullview#page/1/mode/2up

- Sudip Bose, “The Cult of Johanna Martzy,” The American Scholar, January 18, 2018, https://theamericanscholar.org/the-cult-of-johanna-martzy/

- https://www.suedostschweiz.ch/kultur-musik/2020-09-25/kaltes-konzert-in-der-aula

- Glenn Gould, “We who are about to be disqualified salute you!”, in The Glenn Gould Reader, ed. Tim Page (Vintage, New York, 1990), 253.