There have been many speculations and assumptions made about Carlo Bergonzi (1683–1747) and his contribution to Cremonese violin making. While there is no doubt that he was a great and meticulous craftsman in the tradition of Amati and Stradivari, as well as an individual and stylish artist, his status and occupation in Cremona is far from clear. There is a common view of the typical Bergonzi model, with narrow center bouts, big, open-cut Stradivarian soundholes set low and wide, and a distinctive slender scroll with widely projecting eyes. Players hold them in similar regard to the instruments of Stradivari and ‘del Gesù’, often asserting that their characteristic response lies somewhere between the two.

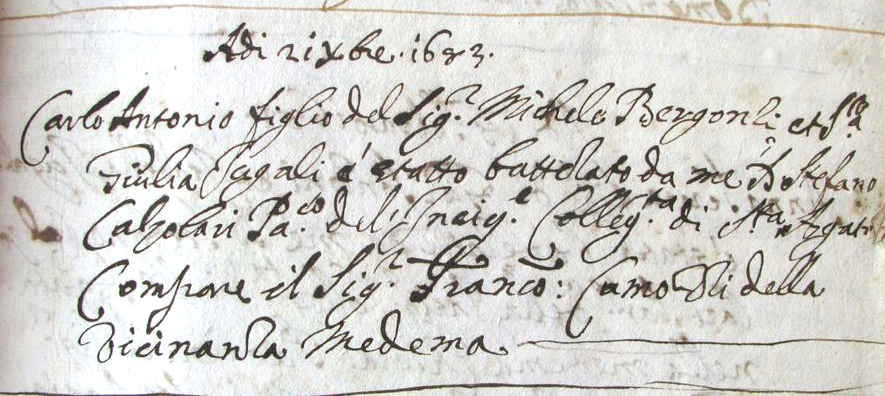

The record of Carlo Bergonzi’s baptism in the Parish of Sant’Agata. Photo courtesy Carlo Chiesa and Duane Rosengard

And yet in all the collected published works barely more than 50 of his instruments are recorded, and there are possibly as few as ten surviving reliable labels. In historical accounts we read musings about an apprenticeship with Stradivari or Guarneri ‘filius Andreae’, and a life that encompassed both the great golden age of Cremonese lutherie and its apparently catastrophic decline. How can we assess a craftsman on such a small amount of verifiable work, which amounts to around two instruments for each year of his working life, and begin to discriminate between periods of development and maturity?

In 2010 the revelatory exhibition of Bergonzi’s work held in Cremona, curated by Christopher Reuning, provided a vivid new understanding of this enigmatic maker, assembling a good half of his known work. Underpinning this was startling new information, brought to light thanks to the research of Carlo Chiesa and Duane Rosengard, [1] which has led to a reassessment of Bergonzi’s entire life. The period of his creativity began in about 1716 according to the earliest account of him, given by Count Cozio di Salabue in 1816. [2] Like most commentators since then, Cozio assumed Bergonzi to have been a pupil of Stradivari. However, the new hypothesis, soundly based on observation and the archival research of Chiesa and Rosengard, is that Bergonzi’s first teacher was in fact Vincenzo Rugeri.

Vincenzo Rugeri’s workshop was close to the Bergonzi family home, and would have been the obvious source of employment for the young Carlo

The Rugeris are as mysterious in their way as Bergonzi himself. The long-standing assumption in their case that Vincenzo’s father, Francesco Rugeri, was a pupil of Nicolò Amati has also been thrown into doubt, and a closer relationship between Francesco Rugeri and Antonio Stradivari seems more than likely. Francesco was a prolific maker, steeped in the style of Amati, although exhibiting small but significant technical departures from Amatese methods and working outside of the city of Cremona in the northern parish of San Bernardo. Vincenzo was the youngest of his sons and the last active member of the family after the death of Francesco in 1698 and his brother Giovanni Battista in 1711. The Rugeri style developed considerably in his hands.

A pleasing chronology identified by Chiesa shows that Vincenzo Rugeri’s workshop, established independently from his father in the 1690s, was close to the Bergonzi family home, and would have been the obvious source of employment for the young Carlo, who reached the usual age for apprenticeship in about 1696. Furthermore, Rosengard has discovered close personal and financial connections between the two families.

Carlo Bergonzi’s father, who seems to have been a baker with no obvious connection to violin making, died in 1697 when Carlo was 14. About that time Girolamo Amati II, the heir to Nicolò, left Cremona and effectively closed the almost 150-year-old family workshop. Giuseppe ‘filius Andreae’ was still very active in his shop ‘at the sign of St Theresa’, but it would seem that his business by then was in decline. By 1717 his eldest son, Pietro, had left for Venice and the younger son, Giuseppe ‘del Gesù’, departed the family home in 1722. Vincenzo Rugeri seems to have flourished in the last years of the 17th century, buying property around his new workshop, but his will drawn up in 1719 indicates that he too experienced a decline in circumstances, according to Rosengard.

Stradivari’s radical departures from the traditional Amati style had changed the prospects of every violin maker in Cremona, and Carlo Bergonzi was among the first wave of craftsmen directly influenced by him

Although we know of more instruments by Vincenzo than either of his brothers, Giacinto and Giovanni Battista, his recorded output is still meagre. There is no reliable catalog of Vincenzo’s works, but the most comprehensive listing available, the Cozio Archive, shows no more than 15 instruments attributed entirely to him throughout his life, in which some 30 years were spent independent of his father. Stradivari’s productivity was at its height in 1708, to which year no fewer than 22 instruments can be attributed, and his annual output remained in the high teens until a decline to a significant low point of only seven known instruments from 1723.

The appearance of new work from Bergonzi and ‘del Gesù’ in the 1720s thus seems in some ways to run against the grain. Stradivari’s radical departures from the traditional Amati style had changed the prospects of every violin maker in Cremona, and Vincenzo Rugeri, Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ and Carlo Bergonzi were the first wave of craftsmen directly influenced by him. It may be entirely fair to wonder if they too were engaged in doing some sort of outwork for the Stradivari workshop. They all adopted the low archings and the deeper red varnish of his Golden Period, but the signs are that work for other violin makers in the city was becoming harder to come by. In violin making terms, the decade from 1720 to 1730 in Cremona was tumultuous, and a challenging time for a young violin maker to find his feet.

In part 2, John Dilworth looks in detail at the surviving works by Carlo Bergonzi.

Notes

[1] Carlo Bergonzi, Alla scoperta di un grande Maestro, ed. Christopher Reuning, Fondazione Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, 2010.

[2] Count Cozio di Salabue, Memoirs of a Violin Collector, ed. Brandon Frazier, 2007.

Other sources

Duane Rosengard, Carlo Bergonzi and his Son, ed. Christopher Reuning, Consorzio Liutai Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, 2010.

Dmitry Gindin and Duane Rosengard, The Late Cremonese Violin Makers, Edizioni Novecento, 2002.

John Dilworth, Cremonese Mystery Man, The Strad, vol. 106 no. 1262, June 1995.