The historical British tradition of lutherie has relatively few outstanding violin makers; the names of John Lott and Daniel Parker are the best known of a handful of native-born luthiers, while Fendt and Panormo brought the benefits of experience in their own homelands before arriving in London. But British-made cellos are held in high regard, and they are gathering prestige and appreciation as time goes on.

The 18th and 19th centuries in London provided a rich source of cellos from makers working on an almost industrial scale – not approaching the volume of the Mittenwald, Markneukirchen or Mirecourt families perhaps, but remarkable and intriguing in its way. Wamsley, Banks, Forster, Kennedy, the Hills, Dodd and many others seem to have maintained a staggering output into what must have been a highly receptive domestic market. Some seem to have made almost as many cellos as violins and violas, a practice not duplicated by any continental luthiers, and certainly not by the classical makers of Cremona. While this has helped to make British cellos distinctive and desirable today, the reasons behind this focus on the bass instrument of the quartet are not immediately obvious.

John Rose tenor viol, 1598. Ashmolean Museum, WA1939.33, University of Oxford. Photo: Tucker Densley

In the 17th century, London belonged to the viol makers. Dozens of craftsmen, from the eminent John Rose in Bridewell Palace, to Samuel Pepys’ viol maker Mr Hunt in St Paul’s Churchyard and Henry Jaye in Southwark, provided musicians and their noble patrons with elegant instruments. In a way, London was the Cremona of the viol, and English viols were held in high esteem in Europe. John Rose (who actually belongs to the late-16th century) was famously ‘as much… commended in Italy as in his own country’ as contemporary account books had it. [1] This opinion was endorsed abroad by Vidal and Rousseau in France and Eisel in Germany. [2] Prince Ferdinand of Tuscany (1663–1713), for whom Stradivari made the famous Tuscan set of instruments, owned ‘a small English viol da gamba made by James Jasbery in Fetter Lane, London’. [3] Jacob Stainer’s viol pattern was reportedly taken from an English viol played by William Young, violist to Archduke Ferdinand in Innsbruck. [4]

An astonishing number of makers whose names are largely unfamiliar today continue to reveal themselves, but more often through archival documents than in the fragile instruments they made. By 1700 viol makers were well established in Southwark, Bishopsgate, Aldgate and Piccadilly, as well as in Oxford, York, Kent and Somerset. [5] This affection for and loyalty to the viol may well have hindered the initial development of the cello in England, but it also meant there were plenty of skilful craftsmen disposed to making large bowed stringed instruments when the cello finally took its place in English music.

Composer and cellist Nicola Haym pictured at the harpsichord in ‘Prova di un’opera’, by Marco Ricci c. 1709. He is thought to be one of the earliest musicians to bring the cello to England

The cello first came to prominence in Italy, with the earliest-known surviving example being the ‘King’ Andrea Amati cello dating from around 1570. Italian players were prominent in the development of the instrument’s repertoire. Domenico Gabrielli (1659–1690) and Petronio Franceschini (1651–1680) from Bologna are seen as the first virtuosi of the instrument and its arrival in England is in all probability due to Nicola Haym of Rome (1678–1729), who led a four-strong cello section established in the Haymarket Theatre orchestra in 1707. [6]

A Tecchler… would have seemed a majestic beast to English audiences, who up until that point would have been more familiar with the bass violin

Haym would certainly have played a large-form (c. 79 cm) cello. It would be nice to think it may have been a Tecchler, which would have seemed a majestic beast to English audiences, who up until that point would have been more familiar with the bass violin.

The bass violin is defined in the late-17th-century Talbot Manuscript, [7] where the common instruments of the day are described with their principal dimensions. The violoncello or ‘bass violin’ in that document has a body length of 2’4” (711 mm) and surviving 17th- and early 18th-century English instruments by William Baker, John Barrett, William Lewis and Barak Norman pretty much conform to this. It was a very small cello, but oddly tuned a semitone lower than the modern instrument, to B flat. These bass violins were the chosen instruments of some English players, while the bass viol still dominated formal performance. The Duke of Chandos kept an orchestra in his London homes in Edgware and Albemarle Street, which in 1720 included four Stainer violins, bass viols by Barak Norman and Henry Jaye, and a ‘violincello or bass violin by Mr Meares’, [8] probably a typical mixture of voices for the period. The Italian cello, a good three inches or almost 8 cm longer in body length and tuned in C, must have seemed a different instrument altogether.

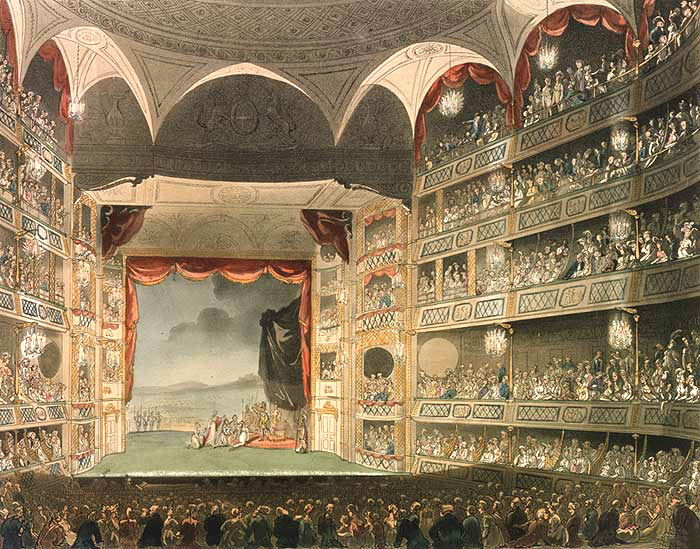

The interior of Drury Lane Theatre, where Cervetto was principal cellist from 1728

Perhaps the single greatest influence on the development of the modern cello in England was Giacobbe Cervetto (1680–1783) from Livorno, who settled in London as principal cellist at the Drury Lane Theatre in 1728. Charles Burney, author of the ‘History of Music’ published in 1776, gave his opinion that Cervetto was responsible for bringing the cello into favor in England, ‘and made us nice judges of that instrument’. This statement suggests that the Italian cello was hitherto not familiar to English audiences. Cervetto and his son James, who was born in England in 1747, taught a generation of English cellists including Robert Lindley (1776–1855) of Rotherham and John Crosdill (1751–1825) of London.

Another presumed influence on musical fashion was the young Prince of Wales, Frederick, son of George II and born in Germany. He arrived in England in 1728, already with a highly romantic reputation, and was a keen musician, playing both violin and cello. The famous 1733 portrait by Philip Mercier in the National Gallery shows him with his sisters, playing his cello, a fine Stainer-looking model with pale golden-yellow varnish.

Portrait of Frederick, Prince of Wales, with his sisters, by Philip Mercier

One of the most famous extant Stradivari cellos, the large, original and uncut ‘Lord Aylesford’, was bought by the Earl of Aylesford (probably Heneage Finch, 1751–1812) from another Italian musician in London: Felice Giardini (1716–1796), who lived in the city from the mid 1750s to 1784 as leader of the Italian Opera at the Haymarket Theatre. This was possibly the first Stradivari cello in England and remains one of the few uncut early Stradivaris of the large form. According to Simon Andrew Forster, [9] Cervetto had previously brought several Stradivaris with him to England, said to have come direct from Stradivari’s workshop, but had to return them to Cremona since he could not raise the asking price of £5 at the time. A little patience might have paid off eventually. Only a few years later the English bass viol and bass violin players had evidently been won over by the Italian cello.

In part 2 John Dilworth looks at which British makers took advantage of the new fashion for the cello.

John Dilworth is a maker, writer and expert. He has written extensively about fine instruments and their makers, and is a co-author of ‘The British Violin’, ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ and ‘The Voller Brothers’ among other books.

Notes

[1] Bridewell Court record books, 9 August 1561.

[2] Vidal, Instruments; Rousseau, Traite; Eisel, Musicus; cited in Fleming, Violin Making in England c. 1580–1660, PhD thesis, Oxford 2001.

[3] Unpublished documents reported by G. Livi to Alfred Hill, Hill Archives.

[4] Walter Senn, J. Stainer, der Geigenmacher zu Absam, Innsbruck 1951.

[5] Michael Fleming, Violin Making in England c. 1580–1660, PhD thesis, Oxford 2001.

[6] John Spitzer and Neal Zaslaw, The Birth of the Orchestra, OUP 2004.

[7] Christ Church Library, Oxford, music catalogue ms.1187.

[8] William Sandys and Simon Andrew Forster, The History of the Violin, Reeves, London 1864.

[9] Inventory of the Duke of Chandos, vol 99. art 22 (quoted in the Hill Archive).

See also, The British Violin, BVMA 2000.