Bartolomeo Cristofori was born in Padua on May 4th, 1655, and was hired by Ferdinando de Medici, the Grand Prince of Tuscany, as an instrument maker and repairer in 1688. Ferdinando was an accomplished harpsichord player and a devoted patron of music and the arts. He built up an entourage of musicians and artists from all over Europe, and made Florence a center of musical excellence and innovation. During the time of Cristofori’s employment at Ferdinando’s court, the Medici collection included a variety of keyboard and stringed instruments including examples by Amati and the important Stradivari ‘Medici’ quintet.

Bartolomeo Cristofori: a cello by the maker known as Bartolomeo Cristofori, instrument maker to the Medici court

Bartolomeo Cristofori’s invention of the pianoforte changed the course of music history. A rare and important Cristofori cello is the highlight of our October auction in London. Representing an intersection of the worlds of keyboard and stringed instrument making, this magnificent cello is a prelude to the Florentine lutherie that followed.

By Jason Price October 12, 2023Cristofori was paid a generous salary and given an apartment and a budget for expenses. From the bills and receipts that Cristofori submitted to the court, as well as other contemporaneous accounts, we know that he had a certain autonomy with regards to the other craftsmen in the Ulffizi’s Galleria dei Lavori (the Medici workshops) and that there was great variety in the scope of the work he did for the Prince. His responsibilities, at least for the first ten years of his employment, were to maintain and repair the keyboard instruments of the Prince’s collection and to fabricate new keyboard instruments for the court.

In around 1700, Cristofori invented an instrument that forever changed the course of musical history, “un Arpicimbalo, che fa il piano, e il forte” (a harpsichord that could play soft and loud). The genius behind Crisofori’s pianoforte was that the hammers struck the strings proportional to the force applied by the player thereby creating different volumes and qualities of sound. To enable this effect, Cristofori invented a special ‘escapement’ mechanism: When a key was pressed, a hammer struck the string and then immediately fell away, allowing the string to resonate freely until it was again dampened as the key was released.

One of several paintings by by Anton Domenico Gabbiani depicting musicians at the service of the Grand Prince Ferdinando 1685-90. (Firenze, Galleria Palatina)

It is speculated that Cristofori made around a dozen pianos but only three survive to this day (in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Museo Strumenti Musicali, Rome, and at the Musikinstrumenten-Museum at Leipzig University). Cristofori’s invention wasn’t widely adopted during his lifetime; in fact, it seems there was little fanfare around the instrument’s debut when it appeared in the Medici musical inventory of 1700. But by the mid-century, the pianoforte had altered music history forever.

The nature of Cristofori’s activities for the court changed shortly after the turn of the century. For various reasons, he ceased to receive his monthly stipend in around 1698 and then, when Prince Ferdinando died in 1713, Cristofori’s official patronage came to an abrupt end. Ferdinando’s father, Cosimo III, appointed Cristofori to be curator (custode) of the musical instrument collection in 1716 but it is unclear if this new position was compensated at a similar level, if at all. Though Cristofori’s official duties at the court diminished, he continued to make new instruments, some of which were destined for the Medici collection and some of which, it appears, were made for private clients.

Many aspects of Cristofori’s life remain unknown. Until recently, most sources insisted that Cristofori was an apprentice to Nicolò Amati in Cremona, which we now know is not true. The confusion originated with the fact that a 13 year-old boy named “Cristoforo Bartolomei” was listed in the 1680 census return of the Amati household. The will to see these two strands of musical history converge was so strong that it suppressed the inconvenient detail that Bartolomeo Cristofori, the inventor of the pianoforte, was, at nearly 25 years old in 1680, too old to be the live-in apprentice to a master. Although their names are similar, the two instrument makers cannot be the same person. This coincidence was first observed by the 19th century musicologist Marquis Giovanni de Piccolellis in his book Liutai Antichi e Moderni (1885) and was echoed elsewhere in the violin literature. To his credit, Piccolellis noted that the similarity of names might be only a coincidence and acknowledged that Cristofori’s birth year of 1655 was seemingly incompatible with the almost homonymous apprentice in the Amati workshop.

The will to see these two strands of musical history converge was so strong that it suppressed the inconvenient detail that Bartolomeo Cristofori, the inventor of the pianoforte, was, at nearly 25 years old in 1680, too old to be the live-in apprentice to a master.

Although we know almost nothing of Cristofori’s education and training, we can assume that there must have been something attractive to the music-loving Prince as the evidence suggests that Cristofori was actively recruited to join the court. A contemporary source quotes Cristofori as saying that he didn’t want the job but the Prince made him an offer he couldn’t refuse (che fu detto al Principe, che non volevo; rispos’ egli il farò volere io).

A photograph of a portrait of Bartolomeo Cristofori from 1726. The original was lost in the Second World War.

The most conspicuous gap in our knowledge, however, is the scope of Cristofori’s involvement with stringed instruments. We have copious records of his work repairing and adjusting keyboard instruments, but there are no records concerning the maintenance or construction of bowed stringed instruments. To put it bluntly, there is no documentary evidence that Bartolomeo Cristofori ever trained or worked as a violin maker.

I know of six Cristofori instruments: four cellos, a violin and a double bass. Although few in number, they are remarkably similar in wood choice, varnish, edgework, soundholes and heads and they are consistent enough to confirm that they were made by the same hand. The congruence is confirmed by the general style and appearance and also by quirky particulars, like the fact that the middle strand of the purfling is made of maple in the instruments I have examined. The cellos are made on the same model—a model that we will see was readily ‘at hand’ to the curator of the Medici collection. Dendrochronological examinations support the dates in which these instruments are believed to have been made. The workmanship is refined, confident and unlike the work of an amateur. The proficiency of the arching, the precision and symmetry of the purfling, the fluidity of the soundholes, and above all, the grace of line throughout, give testimony of a proficient master maker.

Should we be concerned that there are so few stringed instruments attributed to Cristofori? I don’t think so. In fact, we can be grateful that there are twice as many surviving stringed instruments as there are pianos(!)

Should we be concerned that there are so few stringed instruments attributed to Cristofori? I don’t think so. In fact, we can be grateful that there are twice as many surviving stringed instruments as there are pianos(!)

The label in this cello is unconventional: a strip of parchment glued to the center joint of the inside back bearing the inscription, “Bartolomeo Cristofori in Firenze 1716.” The surface of the parchment has deteriorated and the script seems to have been overwritten in an effort to enhance it. Perhaps in earlier times it was more legible as both Alfred Hill and Charles Beare insisted that the label was original when they sold and certified the instrument in 1937 and 1987 respectively.

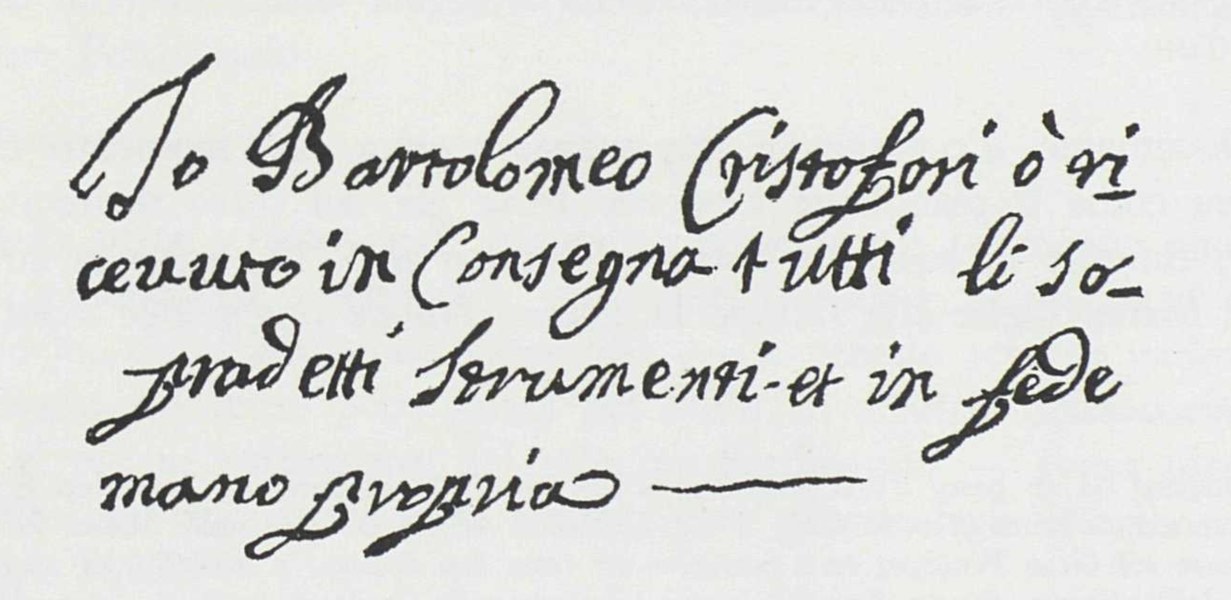

Cristofori’s signature on his 1716 inventory of the Medici collection. (Archivio di Stato dì Firenze)

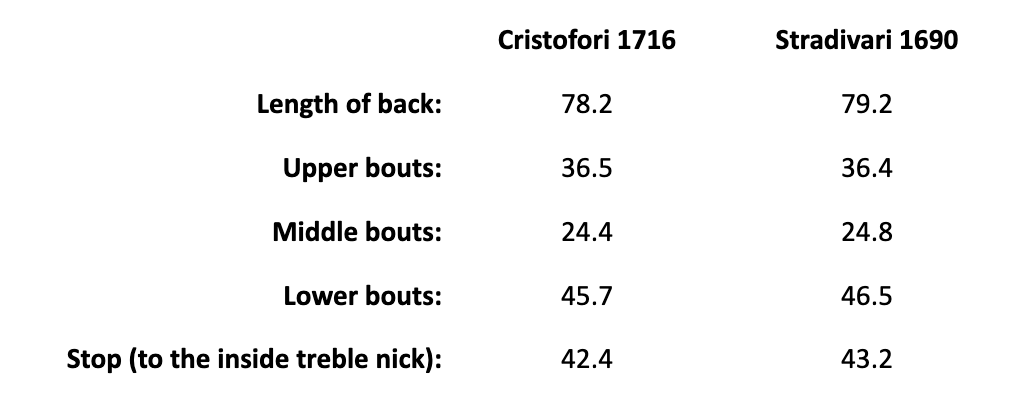

The dimensions of this cello have not been altered and the back length is 78.2 cm. It’s not surprising that this is a large model cello; the newer smaller-pattern cellos like Stradivari’s forma b were only beginning to come into fashion in the early part of the 18th century. Cities like Florence and Rome continued the tradition of making large model bassettos well past the middle of the century.

It’s obvious why this instrument was chosen as a model; it was the best cello in the Medici collection.

It’s also no surprise which instrument, specifically, was chosen as a model. Two years after Cristofori relocated to Florence, a special delivery of stringed instruments arrived to the Medici court that, no doubt, fascinated and inspired the many musicians and instrument makers of the court. In 1684 the Cremonese Marchese Bartolomeo Ariberti commissioned a quintet of instruments from Antonio Stradivari as a gift for the Grand Prince Ferdinando. The instruments were delivered six years later and the 1690 ‘Medici’ cello has resided in Florence ever since. In 1863, it was added to the collection of the Conservatorio Luigi Cherubini and is currently exhibited in the Museo degli Strumenti Musicali, a part of the Galleria dell’Accademia.

Dimensions of this 1716 Cristofori cello compared with Stradivari’s 1690 ‘Medici’.

For the entire history of violin making, makers have learned from and copied the instruments that lived nearby (in Paris, Jean Baptiste Vuillaume copied the ‘Duport’, but in Brussels, his younger brother copied the ‘Servais’). The dimensions, proportions and curves of this Cristofori cello are a near perfect match to those of the ‘Medici’. There are slight variations at the corners and the shape of the upper bouts has been made less round resulting in a body length which is 10mm shorter than the 1690 instrument. The placement of the sound holes is the same in both cellos but the stop length of the Cristofori is 8mm shorter, a result of the change to the upper bouts. It’s not a copy, necessarily, but it’s obvious that this instrument was chosen as the model; it was the best cello in the Medici collection.

The Medici documents indicate that Cristofori relied on the collaboration of various cabinetmakers, general woodworkers and apprentices (ebanisti, legnaioli, garzoni, etc). It is also important to consider the possibility that Cristofori relied on the assistance of other makers for the stringed instruments he made. This doesn’t make his instruments any less important or legitimate. The master of a workshop—particularly an entrepreneurial workshop—needed to rely on others. It was the same case in Nicolò Amati’s and Antonio Stradivari’s ateliers.

It has been suggested that Giovanni Battista Gabbrielli might have made instruments for Cristofori. This makes an attractive origin-myth for the long and distinguished Florentine tradition that followed, but unfortunately Gabbrielli was just 15 years old when Cristofori died in 1732 and thus too young to have had a hand in any of the Cristofori instruments we know. There are discernible stylistic similarities between the work of the two makers, in particular the archings, the scrolls and the straw-coloured varnish and ground. Gabbrielli’s sound holes tended more towards a Stainer model, but Cristofori’s influence on Gabbrielli is clear and the will to connect these two makers understandable. I find it amusing that many reference books from the 19th and 20th centuries (Valdrighi, Luttgendorf, Vannes, Jalovec, Henley, etc.) list two fictional violin makers, Bartolomeo Gabbrielli and Cristoforo Gabbrielli who were presumed to be the father and uncle of Giovanni Battista (we know from the recent research of Maria da Gloria Leitao Venceslau in The Makers of Tuscany that Gabbrielli’s father’s actual name was Gabbriello).

It has also been suggested that Pietro Antonio Malvolti might have been a pupil and collaborator of Cristofori. Although the dates of these two makers line up nicely, the instruments attributed to Malvolti vary greatly from the Cristofori instruments we know.

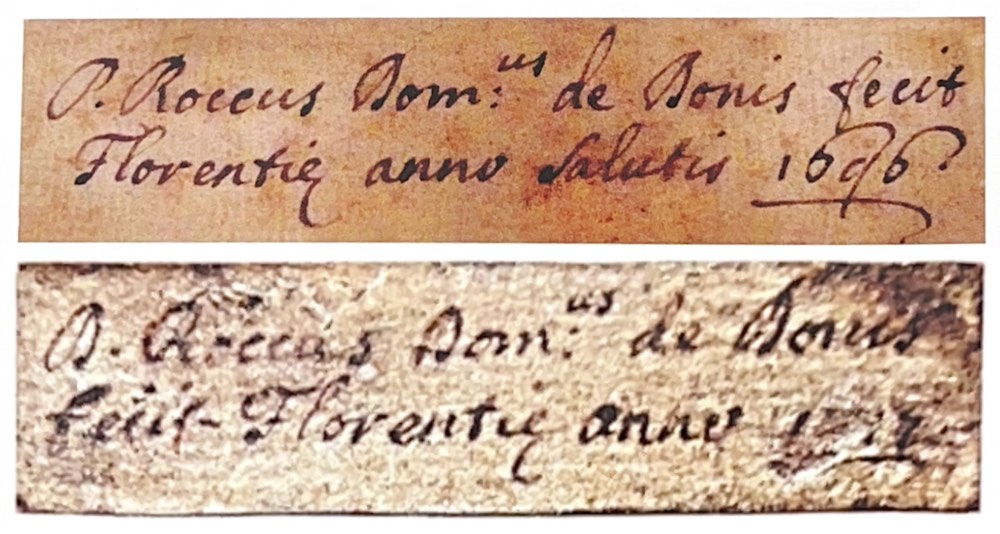

Another hypothesis is that there was some sort of collaboration between Cristofori and the violin maker Rocco Domenico Doni who made stringed instruments for the Medici court at around this time. I’m not the first to connect these two makers, Florian Leonhard hinted at a similar theory in his recent reference, The Makers of Tuscany. Interestingly W. E. Hill & Sons also made this observation but they mis-transcribed the maker’s name. When a Doni cello came through the Hill shop in 1921 Arthur Hill wrote that it was “an early, interesting Florentine cello by the little known maker … P. Roccus Dominicus de Bonis … made in 1694 [that] reminds us in many respects of the work of the celebrated Bartolomeo Cristofori.” Seeing the two manuscript labels that are illustrated in Leonhard’s book, it’s easy to understand how the Hills misread Doni’s script. In fact, many of the standard reference books list a maker from Florence or Cortona as “de Bonis” which seems likely to be our man Doni.

Labels from Rocco Domenico Doni from 1696 and 1697 as illustrated in Florian Leonhard’s The Violinmakers of Tuscany.

The 1696 Doni cello currently in the Cherubini collection in Florence is of unusually large proportions with a back length of over 80 cm. The model is different from the Cristofori cellos but the varnish and workmanship of the sound holes and edges is rather similar. Another Doni cello appeared at the Philadelphia firm of William Moennig & Son firm in early 1980s. They attributed this instrument to “P. Roccus, Firenze, 1694”, also a mis-transcription and raising the possibility that this was the same cello as the one that came through Hills sixty years prior. An inspection of photos from the Moennig firm shows an instrument that was originally of a large model but has since been reduced. The c-bouts, edges and sound holes closely resemble those of Cristofori; the maple is identical to that used on the 1716 cello; and the details of the corners and purfling—in so much as we can see them in the black and white images—are convincingly similar. Interestingly, the 1700 Medici inventory mentions two Doni cellos, one dated 1696, which is in the Accademia Collection today, and another dated 1694, which is missing.

This remarkable cello is an exceptional and important instrument. Our attribution, “made by the maker known as Bartolomeo Cristofori,” is designed to be precise, conservative and reflect the necessary nuances of all that we know to be true about Cristofori, and all that is yet to be learned. What is, however, certain, is that this is an exceptional instrument and a crucial bridge at the intersection of the keyboard and stringed worlds.

Provenance:

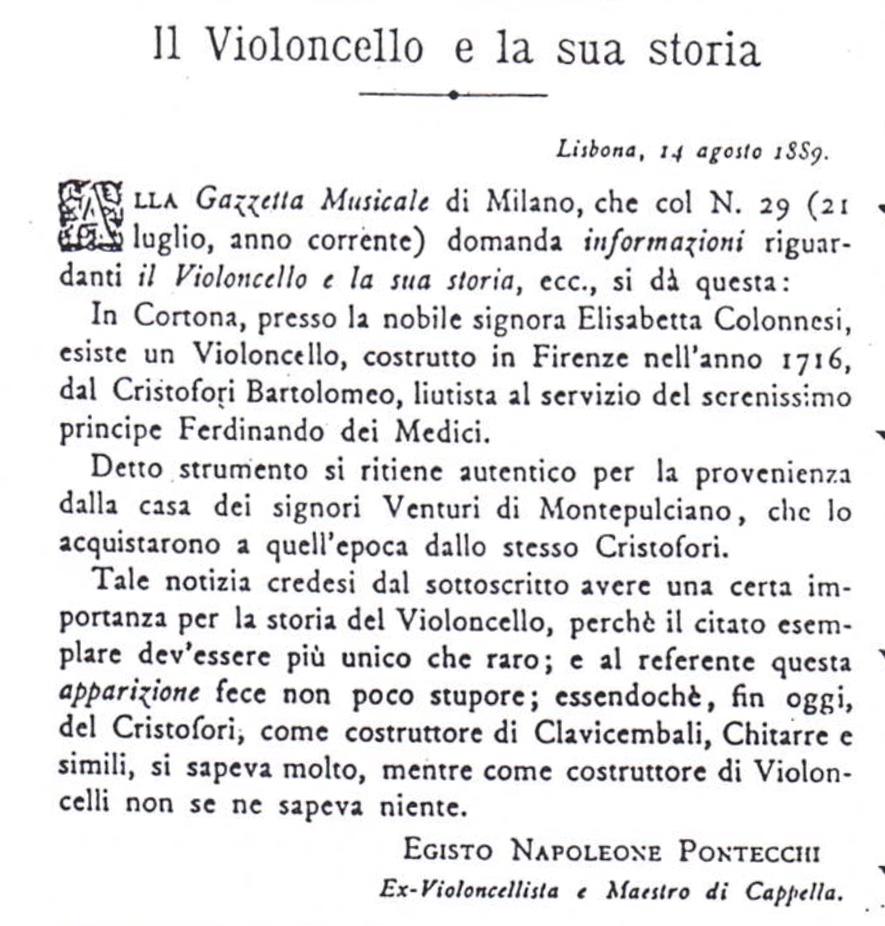

In a letter to the Gazzetta Musicale di Milano in 1889, the cellist and composer Egisto Napoleone Pontecchi wrote of a 1716 Cristofori cello in the possession of a noblewoman named Elisabetta Colonnesi in Cortona, recounting how the cello was purchased from Cristofori by the Venturi family of Montepulciano. This may well be our 1716 cello. But this story, tantalizing as it is, should be taken with a pinch of salt: This may be no more than the usual story of nobles with a Strad in the attic. However, Cristofori is hardly a name that fiddle finders look out for and the fact that the letter cited the specific year in which this cello was made is a reason to take it seriously. (The provenance of the other c. 1716 Cristofori cello would seem to exclude it.)

In 1909 a man named Whitcombe from Cheltenham sold this cello to the Hills. The Hills then sold it to Col. John Hopton, an accomplished amateur cellist who was appointed a Director of the Royal Academy of Music in 1922. Hopton died in 1934; three years later, in 1937, the Hills sold the cello to the Welsh cellist David Ffrangcon Thomas. In 1987, it was sold by J & A Beare Ltd. to its current owner, a Swiss amateur cellist and collector.

A letter to the Gazzetta Musicale di Milano in 1889 calls attention to a 1716 Cristofori cello in the possession of a noblewoman named Elisabetta Colonnesi in Cortona.

References:

Stewart Pollens, “Bartolomeo Cristofori in Florence” in The Galpin Society Journal, March 2013, Vol. 66, pp. 7-42.

Michael Kent O’Brien, Bartolomeo Cristofori at court in late Medici Florence, The Catholic University of America, 1994.

John Dilworth, “Two-Part Invention” in The Strad, January 1985, pp. 668-670.

Alberto Giordano, “Performer, Inventor, Luthier” in The Strad, May 2013, pp. 59-65.

Florian Leonhard, The Makers of Tuscany, Cremona: Edizioni Novecento, 2022.

Browse the Cozio Archive

210,000+ Photographs

36,000+ Instruments & Bows

3,500+ Violin & Bow Makers

11,000+ Historical Owners

57,000+ Auction Results

14,000+ Certificates & Documents

Sign up to our newsletter