The ‘Baltic’ takes its name from “an old Baltic family by the name of von Giese which no longer exists.”[1] As far as historical accuracy goes, this isn’t much to work with. Nevertheless, that’s what the Berlin violin dealer Philipp Hammig wrote to Rudolph Wurlitzer in 1946. The ‘Baltic’ is what the Wurlitzers called the violin, and this became its name.

Hammig’s family firm had sold the ‘Baltic’ eleven years earlier, and the firm’s archives give a slightly different account of its past. According to Wilhelm Hermann Hammig’s notes, the previous owner of the ‘Baltic’ was a member of the Giese family of Rathenow, a small town in Brandenburg, 90 km northwest of Berlin.[2] The Giese family weren’t nobles; they were merchants (the ‘von’ was added by Hammig), and although Rathenow is far inland from the Baltic Sea, several generations of the Giese family were successful shipowners and sea captains who likely traded up and down the Baltic coast.

Hammig sold the violin to Dr. Walter Sochaczewski, a successful pediatrician in Hannover. Sochaczewski had served in the German army as a doctor in the First World War, stationed in Bavaria. In 1919 he married the daughter of a banker from Hannover and in 1922 he opened his practice in a prestigious building in the center of the city. He was particularly interested in Sozialpädiatrie, an interdisciplinary approach to developmental pediatrics which was popular in Germany in the early 20th century.[3]

The Sochaczewski family was middle class and cultured. They had a large library and a piano; chamber music was played frequently in the family home.[4]“You couldn’t be more German than my father,”remembered his daughter Barbara in 2010.[5]

Sochaczewski, a doctor in the German army, was stationed in Bavaria during the First World War. (Photo: Barbara Sochaczewski Dreyfuss from myheimat.de)

In 1933 over 50% of Germany’s pediatricians were Jewish but with the rise of National Socialism, life quickly became dangerous and unsafe for doctors like Sochaczewski. At the beginning of 1935, a prominent Hannover publisher and the head of the anti-Semitic Stürmer Freunde Hannover, Heinz Siegmann, included Dr. Sochaczewski in his Juden in Hannover, an insidious list of Jewish companies, banks, doctors and other professionals.[6] Patients and their families, previously loyal to Dr. Sochaczewski, were bullied into leaving his practice.

Mindful of the worsening political situation, Dr. Sochaczewski and his wife began to think of leaving Germany and the financial consequences such a decision would entail. We don’t know if Dr. Sochaczewski or his wife Ilse played the violin but that doesn’t seem to be the reason he bought the ‘Baltic’ in November of 1935.[7]

If the political situation deteriorated further for his family, a precious yet highly-portable and unassuming violin could be an effective way to transfer wealth without attracting attention.

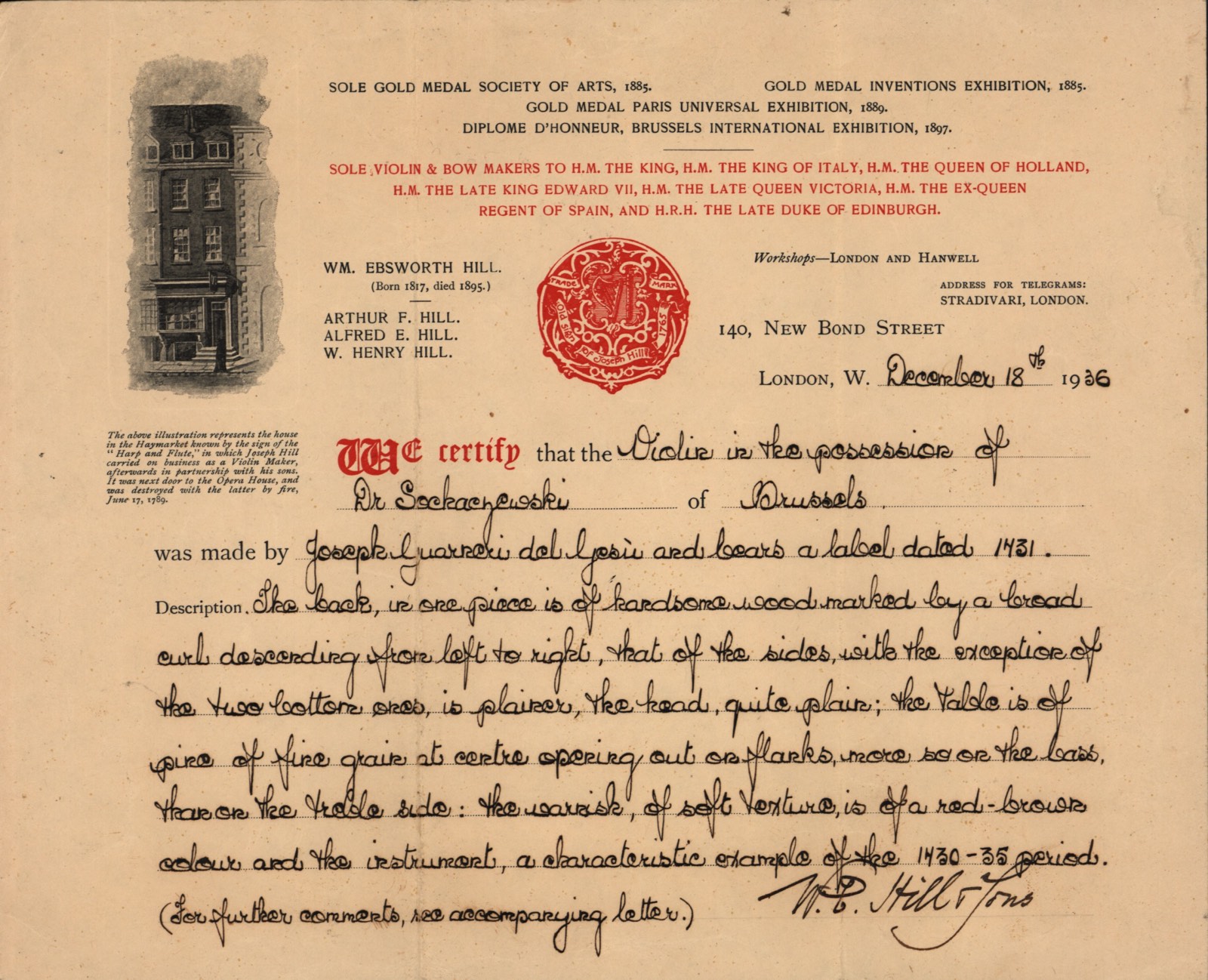

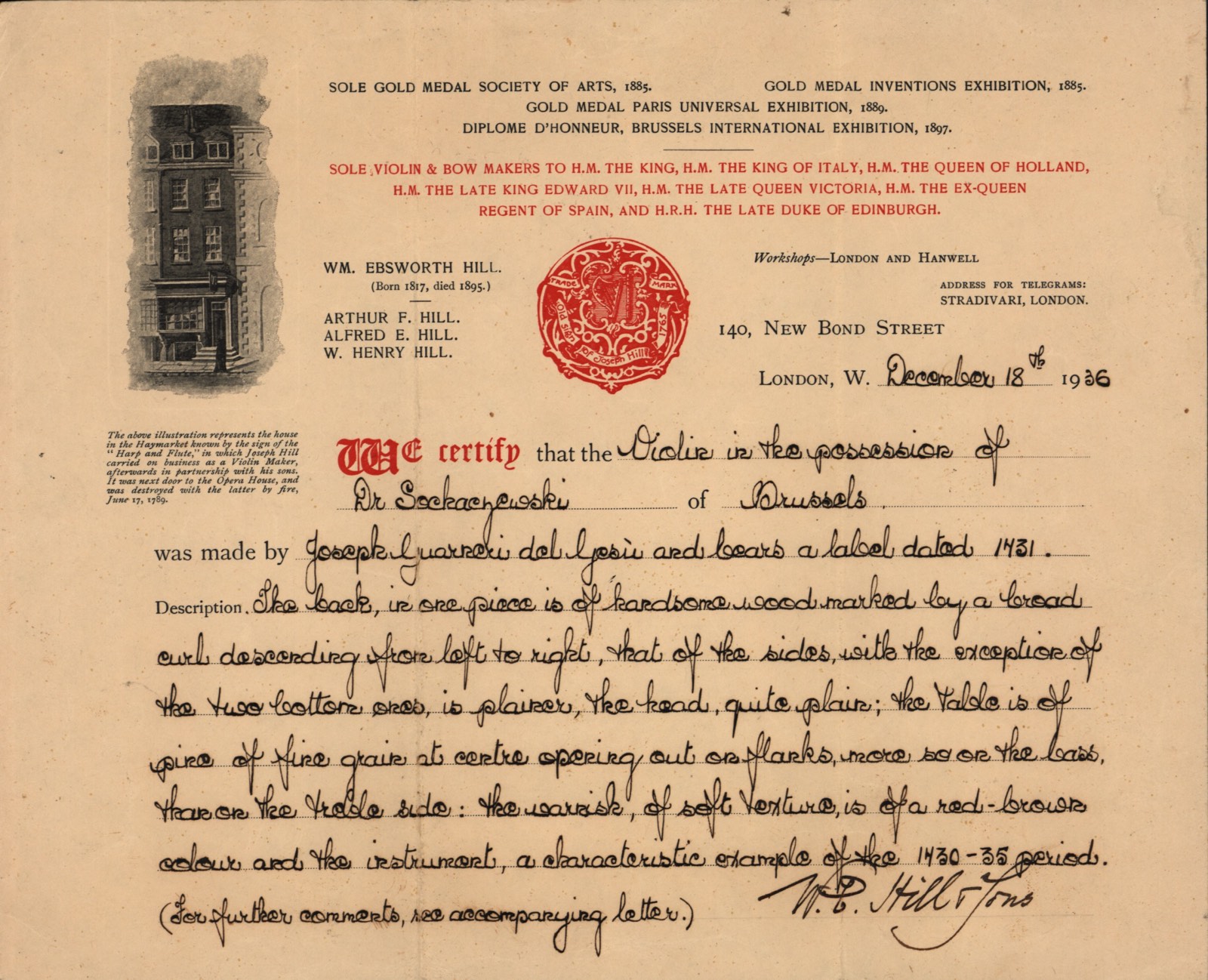

A year later, a police officer whose child had been a patient of Dr. Sochaczewski, tipped him off that soon he was to be arrested and deported.[8] On November 25, 1936, Sochaczewski and his family escaped in secret. The doctor crossed into Belgium; his wife and daughters traveled to Switzerland; and the family reunited in Brussels.[9] Less than a month later, the ‘Baltic’ was in London at the violin dealers, W. E. Hill & Sons. There’s no indication whether the ‘Baltic’ was submitted to the Hills for sale or safekeeping but a certificate was issued for the violin on December 18th in the name of Dr. Sochaczewski of Brussels. The accompanying letter from Alfred Hill noted that the violin was not previously known to their firm, which explains why it wasn’t included in their 1931 monograph on the Guarneri family.[10]

The Hill certificate is issued in the name of “Dr. Sochaczewski of Brussels” less than a month after Sochaczewski fled Germany.

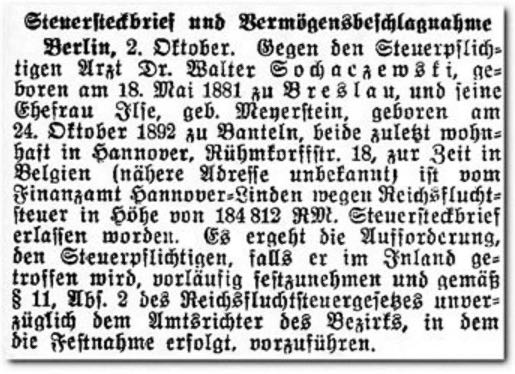

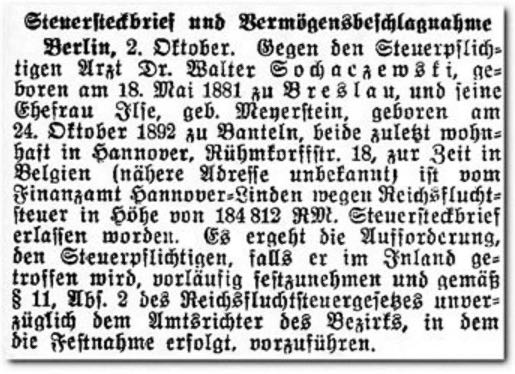

On October 2, 1937 an arrest warrant was issued for Dr. Sochaczewski and his wife by the German tax authorities for non-payment of the Reichsfluchtsteuer. Since 1931 this ‘Reich flight tax’ had effectively prohibited the emigration of affluent, mostly Jewish families by levying extortionate tariffs on their assets.

If Dr. Sochaczewski’s purchase of the ‘Baltic’ was part of a clever strategy to avoid the Reichsfluchtsteuer, the Reich was not going to take it lightly.

An arrest warrant was issued for Dr. Sochaczewski and his wife Ilse for non-payment of the Reichsfluchtsteuer, the tax on German citizens fleeing the country after 1931. (Photo: Barbara Sochaczewski Dreyfuss from myheimat.de).

While Belgium initially granted refuge to Jewish exiles like Dr. Sochaczewski, there were concerns that the far right would gain power and that leaders like Léon Degrelle and his Rexiste party would align the country more closely with its fascist neighbor. Sensing that worse trouble lay ahead, the Sochaczewskis boarded a ship in Antwerp and sailed to São Paolo, Brazil just a year after fleeing Germany. Dr. Sochaczewksi died in Brazil on January 23, 1950 at the age of 68.

The ‘Baltic’, meanwhile, did not travel with the Sochaczewski family to São Paolo. Correspondence from June of 1939 between Alfred Hill and the New York dealer Rudolph Wurlitzer reveals that the violin was in London in the care of the Hills and was being prepared to be sent to Wurlitzers for sale.[11] The Hills and Wurlitzers were close associates in these years. Sales, consignments and referrals flowed freely between them, but mostly the instruments went westward to America where customers and cash were plentiful. The Hills had arranged for Wurlitzer to get the consignment of the ‘Baltic’ and in return, Wurlizer paid the Hills a referral commission. On August 7, 1939 the ‘Baltic’ arrived in New York City on the SS Queen Mary.[12]

Six months later, the Los Angeles branch of the Wurlitzer company sold the violin to Elihu Clement Wilson, an eclectic engineer who had made money in the burgeoning oil industry. Together with his two brothers, Wilson held lucrative patents for tools and technology used to mine and refine petroleum. In addition to the ‘Baltic’, Wilson owned another Guarneri violin, the 1731 ‘ex-Turrettini’ as well as instruments by Stradivari and Bergonzi.

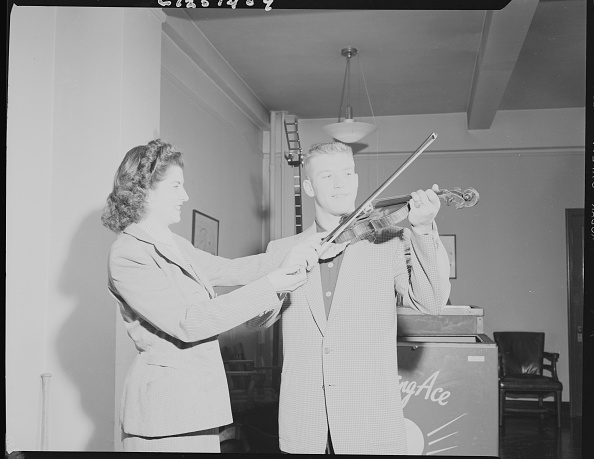

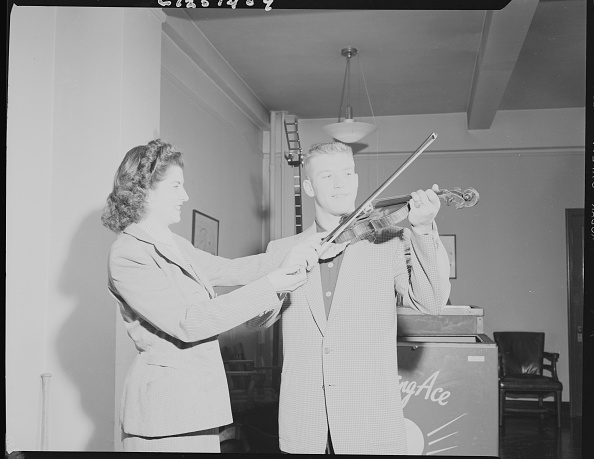

Wilson died in 1950 and in March 1952, Rembert Wurlitzer purchased the ‘Baltic’ from Wilson’s daughter, Elizabeth Wilson Farrar. Shortly thereafter, Wurlitzer sold the violin to the American violinist Dorotha Powers. Powers’s husband Arthur W. Percival had been a piano salesman at the Wurlitzer company and in 1947 he and Eugene Farny, who was Rembert Wurlitzer’s first cousin, started Telecoin Corporation, a company that franchised self-service laundromats. The business flourished in the booming post-war American consumer economy and the partners boasted a profit of $550,000 in the first nine months of 1947.[13] Powers owned two Stradivari violins that she purchased from Wurlitzer — the 1682 ‘Hill, Banat’ and the 1711 ‘Earl of Plymouth, Kreisler’. Interestingly she traded in the latter to finance her purchase of the ‘Baltic’. Among other accomplishments, Powers is remembered for leading the Powers String Quartet consisting of four siblings and for giving lessons to Yankee baseball superstar, Mickey Mantle.

Mickey Mantle, the young superstar baseball player for the New York Yankees, takes lessons from violinist Dorotha Powers in 1954. The original caption read, “there is no danger of the Yankee Stadium losing Mantle to Carnegie Hall” (Photo: Bettmann via Getty Images).

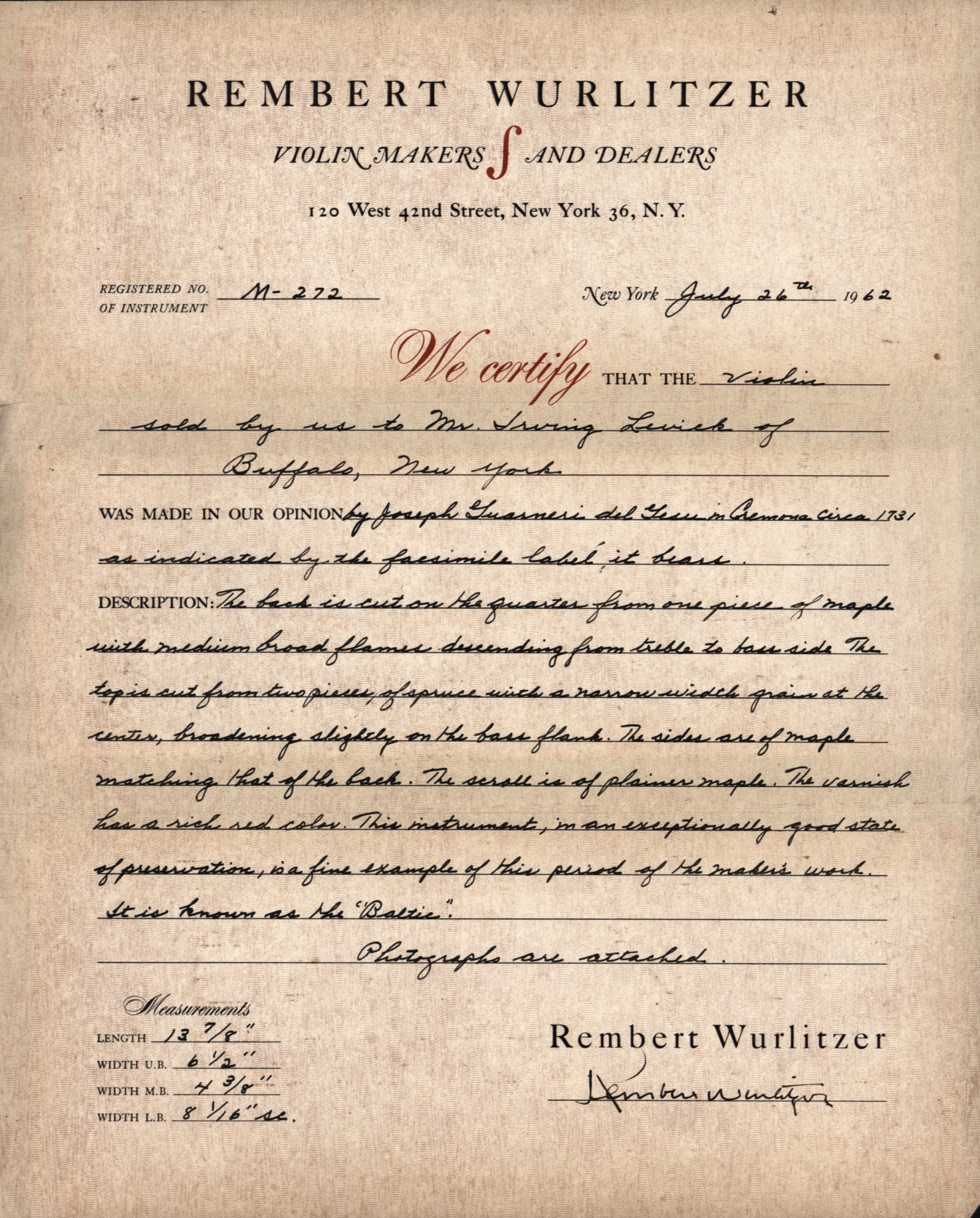

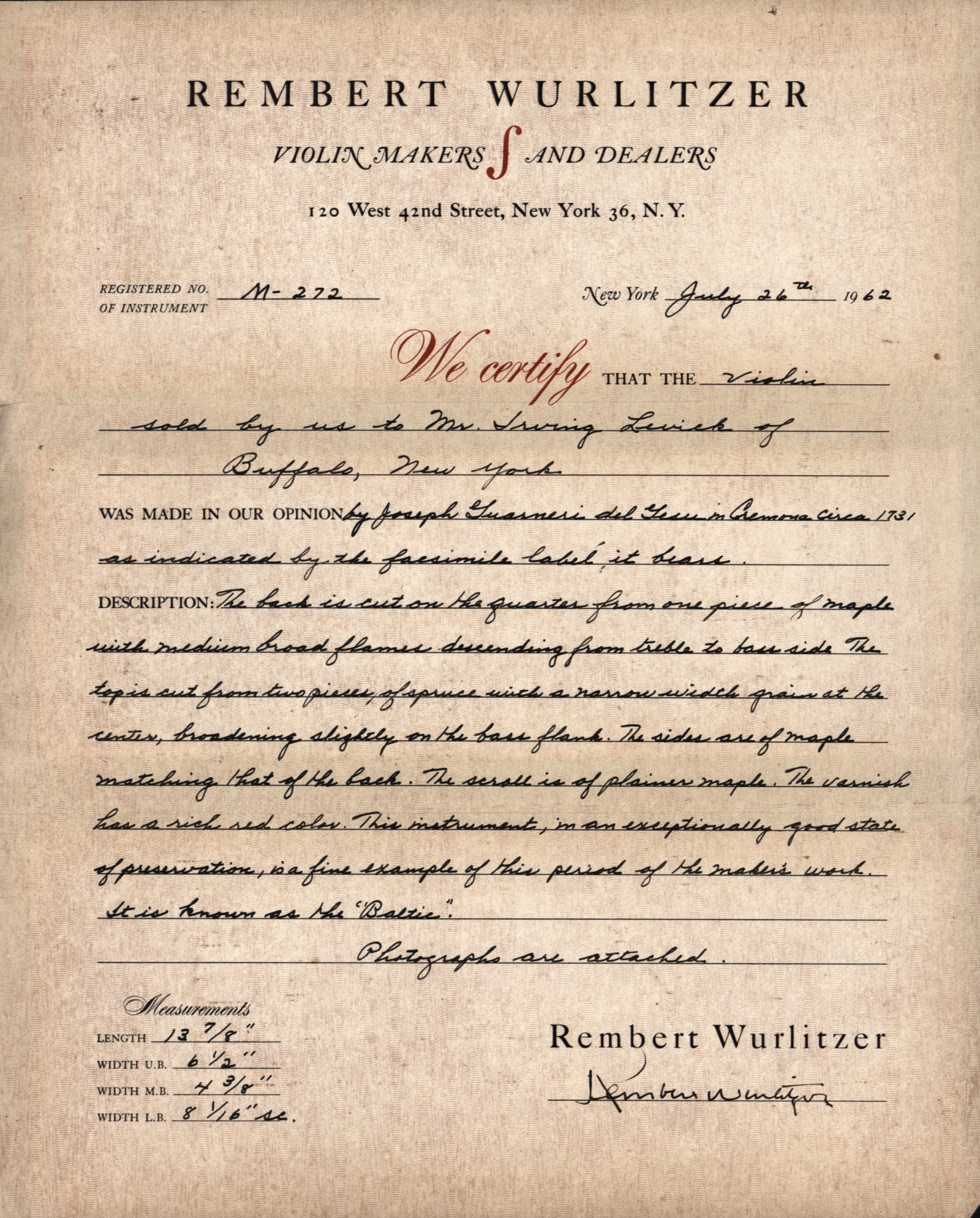

In 1962 the violin came back to Wurlitzers on consignment and this time they sold it to the upstate New York collector, Irving Levick. The Wurlitzer certificate noted that the violin was in “an exceptionally good state of preservation.”[14] In 1971 Levick sold the violin through the Harry Duffy of Miami, who was previously a salesman for the Wurlitzer company, to the California collector, George Gade. Several years later, the ‘Baltic’ was acquired by the Canadian violinist Steven Staryk who concertized extensively on the instrument and made several recordings. In 1979 the ‘Baltic’ was acquired by Chinese American businessman and music patron, Sau-Wing Lam.

The Wurlitzer certificate is possibly the first time that the ‘Baltic’ is given this name. Rember Wurlitzer refers to the violin as in “an exceptionally good state of preservation.”

• • •

Sau-Wing Lam and the Lam Collection

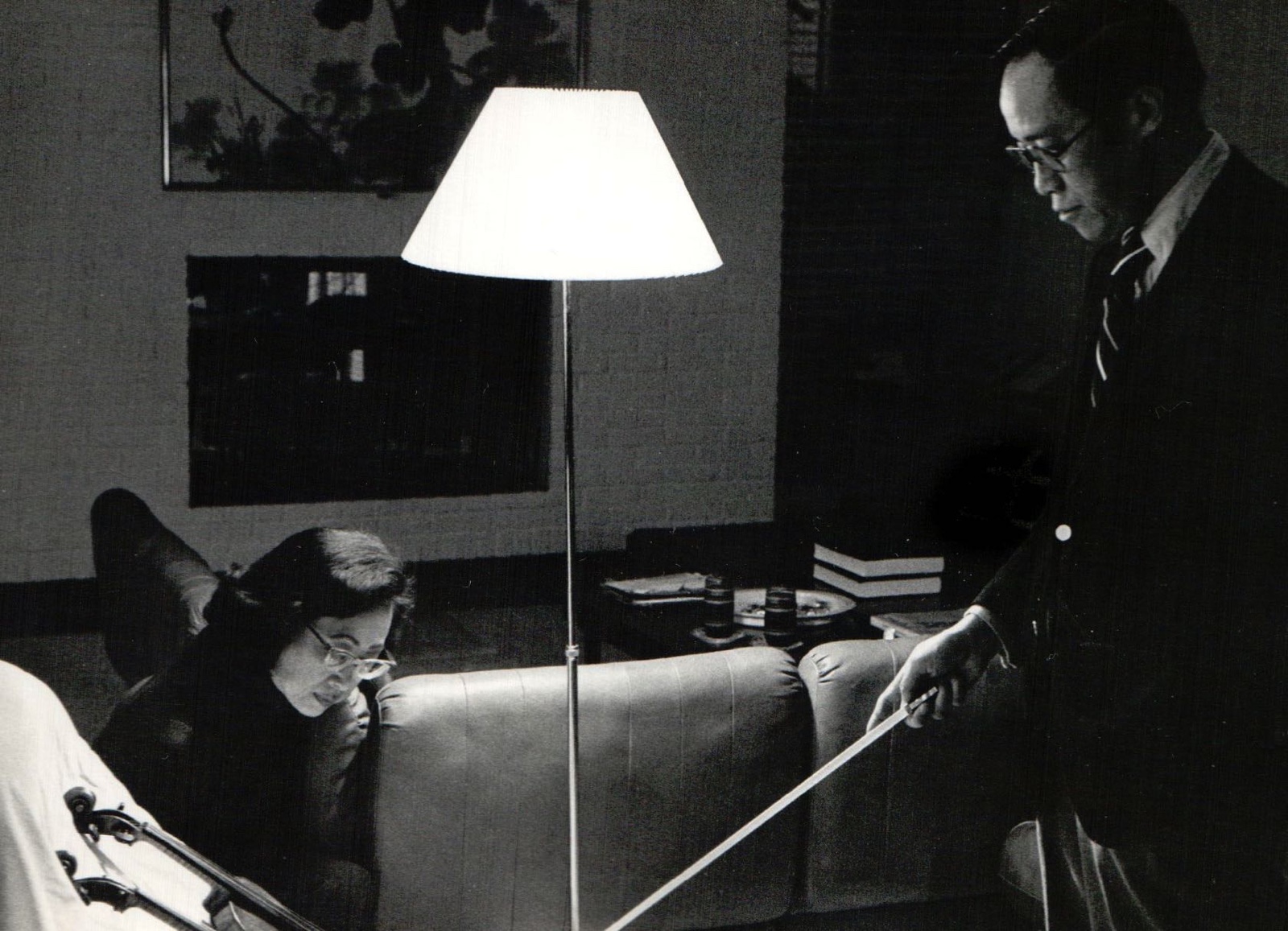

Sau-Wing Lam (Photo: The family of Sau-Wing Lam)

In 1979 Sau-Wing Lam acquired the ‘Baltic’ and added it to his prestigious collection of fine Italian instruments and French bows. It was one of Lam’s last acquisitions and probably his most important. If instruments manifest the personalities of their owners then it’s no surprise that the ‘Baltic’ beams with grace, nobility and warmth.

Sau-Wing Lam was born in 1923 to a Cantonese family in Shanghai, China. His father worked in banking, and together his parents instilled in their nine children the importance of education and curiosity. Perhaps this is what Sau-Wing owed his love of classical music to, seeing as it appeared to have emerged out of the ether. Neither parent displayed any remarkable love for music, and none of the Lam children received music lessons. His passion for music seems, as such, almost innate, as central to his personhood as the senses of sight or touch.

In school, Sau-Wing took up the viola, which was the only stringed instrument available for him to learn. He was hooked. By the time he matriculated at St. John’s University in Shanghai, he was playing in a theater orchestra. Shanghai in the 1930s was a vibrant, vivacious city, thrumming with energy and excitement, and in playing in the orchestra pit, Sau-Wing found himself in the center of the madness. Regularly, he hurtled through the city on his bicycle (sometimes with the orchestra’s French horn player balanced on the handlebars) as he traveled to gigs where audiences awaited enchantment.

Sau-Wing was the sort of man who found all of life interesting. At university, he studied art and journalism until those departments were closed owing to the war; he in turn focused on economics. After graduating, he moved to Hong Kong where he worked for Hang Seng Bank, until, in 1948, he was sent to New York to establish the Dah Chong Hong Trading Corporation’s presence in the United States. Under DCH’s umbrella, he went on to open some of the most successful automobile dealerships in the country.

In New York, Sau-Wing met his future wife Jean, an amateur pianist, and together they played chamber music out of their living room. Following the start of the Cultural Revolution, returning to China became unthinkable. Believing that China was heading in the wrong direction, Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution in 1966 with the aim of purging the country of bourgeois infiltrators and revitalizing the spirit of the communist revolution. Sau-Wing and his wife did not go back to visit China for nearly three decades.

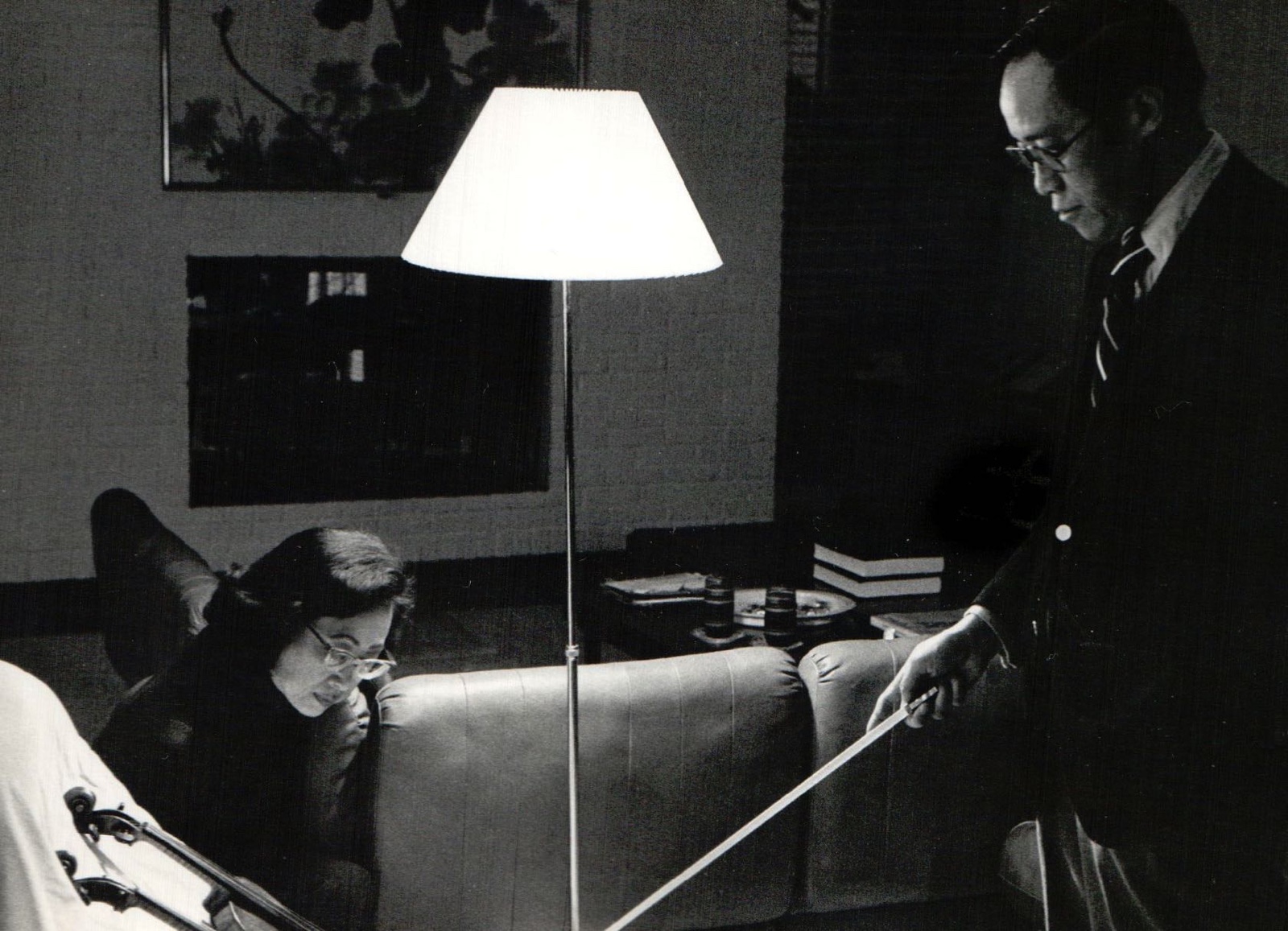

Sau-Wing and Jean Lam in their home in New Jersey. (Photo: The family of Sau-Wing Lam)

Once married, Sau-Wing and Jean lived first in Riverdale, the Bronx, before settling in New Jersey, where they raised four children and assimilated themselves into the local community. Theirs was to be a musical home, though to Sau-Wing’s surprise, none of his children took up stringed instruments, preferring instead the piano, flute, drums, and trumpet. Nevertheless, he regularly invited both amateur and professional musicians to play his outstanding collection of stringed instruments, and to play with him. Through an auction he once won a performance by the Juilliard Quartet, and when they arrived at the Lam home, they found Sau-Wing with his viola ready to play. Afterward, the Quartet joined the Lams for a meal Jean had prepared.

Sau-Wing strove to be, first and foremost, a decent person. He was exceedingly generous and thoughtful, embodying the belief that small acts of kindness could go a long way.

Throughout his life, he offered patronage and support to musicians of all ages, preferring to be on the side-lines rather than in the spotlight himself. His approach to collecting and to music was similar, and as with life, he tried to learn as much as he could about this art that he so loved. Above all, he sought a great sound, and the instruments he assembled in his home were exquisite. To Sau-Wing, they had everything: beauty, history and most importantly, they made music.

Notes:

- Letter from Philipp Hammig to the Wurlitzer company, December 14, 1946 (translation copy)./li>

- Thank you to Michael A. Baumgartner for his discoveries in the Hammig archives.

- “Familie Walter und Ilse Sochaczewski”, Lebensraum-Linden Navigator, http://navigator.lebensraum-linden.de/inhaltsverzeichnis/details/poi-900000088-5201-Familie_Walter_und_Ilse_Sochaczewski.html, accessed on December 29, 2022.

- “Zur Geschichte des altesten Lindener Verkehrsknotenpunktes,”Lindenspiegel, November 2010, http://www.lindenspiegel.co.uk/archiv/2010/Lindenspiegel11-2010.pdf, accessed on 29 December 2022.

- “Zur Geschichte des altesten Lindener Verkehrsknotenpunktes,”Lindenspiegel, November 2010.

- Eduard Seidler, Jüdische Kinderärzte 1933 – 1945 (Basel, Verlag Karger, 2007).

- “Familie Walter und Ilse Sochaczewski”, Lebensraum-Linden Navigator.

- Hammig, W. H. Certificate of authenticity. (Translation copy.)

- “Familie Walter und Ilse Sochaczewski”, Lebensraum-Linden Navigator.

- CV of Dr. Walter Sochaczewski, compiled by Dr. Karljosef Kreter in 2011, Stadtarchiv Hannover.

- W. E. Hill & Sons, Letter to Dr. Sochaczewski, December 17, 1936., reissued November 19, 1971 (accompanying the violin).

- The Business records of the Rudolf Wurlitzer company. Stock card 8971, M272.

- IBID.

- “CORPORATIONS: Wash It Yourself”, Time, December 29, 1947 https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,804450,00.html

- Rembert Wurlitzer Inc., Certificate of Authenticity, July 26, 1962 (accompanying the violin).