For almost as long as his violins have been famous, Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri has been known as del Gesù. It’s an enchanting name for an artisan, evoking a heroic, larger-than-life mythology that has, for centuries, inspired romantic visions of a possessed artist and a god-gifted genius. But this talented craftsman wasn’t always known as del Gesù. The nickname came much later, long after the golden-age of Cremonese violin making had come to an end. As the late violin expert and Guarneri specialist Robert Bein once said, it’s not like his wife yelled upstairs at mealtimes, “Hey del Gesù, dinner’s on the table!”

It’s not like his wife yelled upstairs at mealtimes, “Hey del Gesù, dinner’s on the table!”

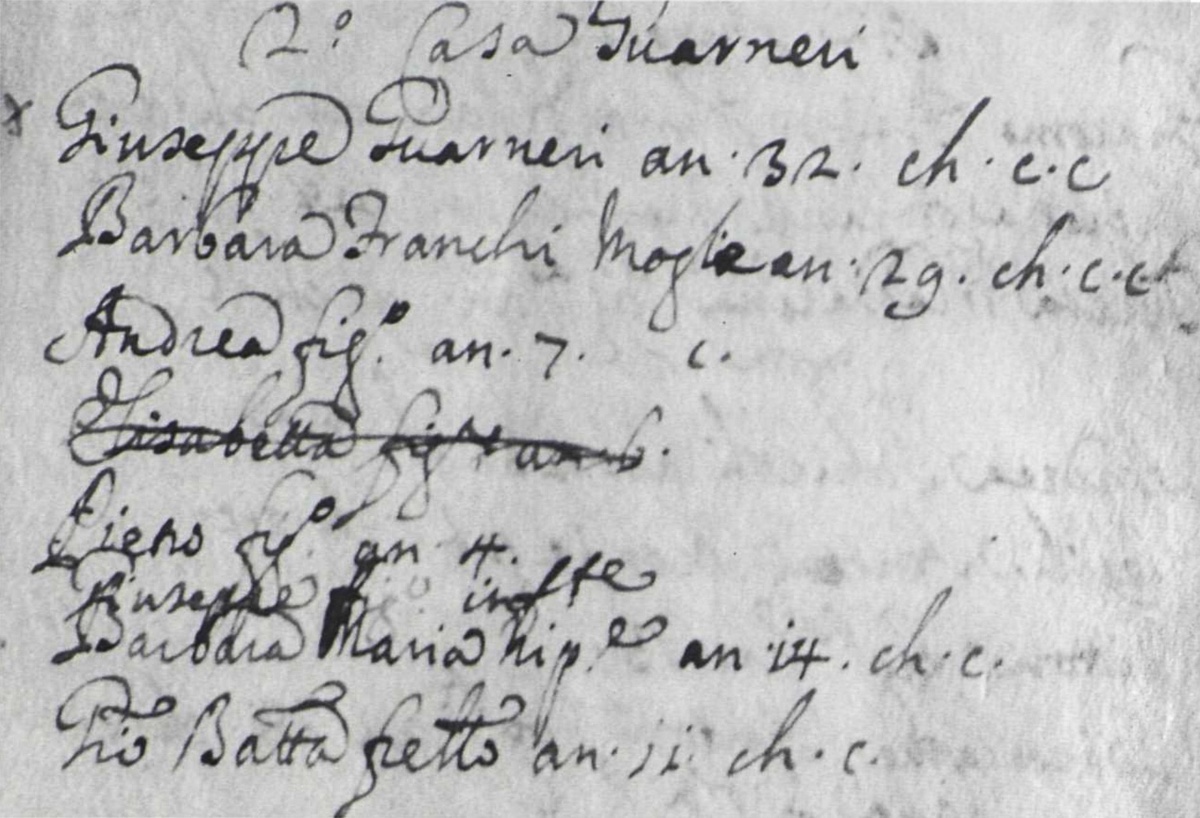

This nickname first appeared in the late 18th or early 19th century when violin experts began to sort out the various makers of the Guarneri family. Confusion arose from the fact that two successive generations were named Giuseppe: the makers we now refer to as Giuseppe ‘filius Andreæ’ (the son of Andrea) and his youngest son, Giuseppe ‘del Gesù’. The latter was christened with the full name of Bartolomeo Giuseppe, but from the beginning he was called simply Giuseppe. Already in the parish census of 1699, recorded just months after he was born, his first Christian name was omitted, and in nearly every subsequent census, record or document in which he is mentioned, including his marriage record, he is referred to as Giuseppe. Bartholomeo was probably given as a formality, so that father and son didn’t have the same name. This issue wasn’t unique to violin makers and even today in Italy naming a child after a living parent or sibling is strongly discouraged –– when flowers arrive for Maria Rossi and there are four Maria Rossis all living at the same address, it’s chaos.

The parish census of 1699. Just months after Bartolomeo Giuseppe was born he was referred to simply as Giuseppe with no mention of his first Christian name. (Photo: Carlo Chiesa)

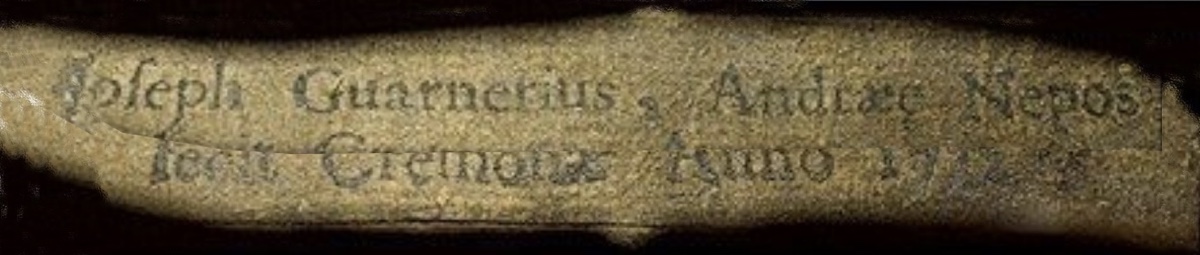

The earliest violin experts and enthusiasts understood that there were two makers named Giuseppe Guarneri but had difficulty working out the relationship between them. In a way, del Gesù himself was partly responsible for this confusion: It was he who broke with the Cremonese tradition of naming parentage on his labels. The Cremonese convention, beginning with the Brothers Amati, was to declare a maker’s lineage by stating the name of his father. Nicolo Amati’s labels went further, telling us that he was both the son of Girolomo and the nephew of Antonio (“Hieronymi Fil. ac Antonij Nepos”). This served to show the relationship of the maker to his master and to underline the importance of familiar traditions. The two sons of Andrea Guarneri did the same by adding “filius Andreæ” (son of Andrea) on their labels, and Pietro of Venice wrote “filius Joseph” (son of Joseph) even long after he left Cremona. At the beginning of his career, “del Gesù” followed this tradition but in an unprecedented way: In his first, pre-1730 label he referred to himself as “Andreæ Nepos” (grandson of Andrea).

The label of the 1728 ‘ Kubelik, von Vecsey.’ According to Count Cozio’s notes, in his first instruments, up to 1730, del Gesù referred to himself as “Andreæ Nepos”.

This label helped experts to understand that there were two Giuseppe Guarneris, but created further confusion because of a linguistic ambiguity. In Latin the word nepos can mean either grandson or nephew so the phrase “Joseph Guarnerius Andreæ Nepos” could mean either nephew of Andrea or grandson of Andrea, and without context or archival research, early experts had no way to know which was correct. Possibly influenced by Nicolo Amati’s nepos reference, many early experts falsely concluded that Giuseppe was the nephew of Andrea.

The confusion was compounded by the fact that several other Giuseppe Guarneris were born in Cremona in the late 17th century. In fact, Andrea Guarneri had two grandsons named Giuseppe. As far as we know only the one later known as del Gesù was involved in violin making but that didn’t stop researchers and biographers from occasionally muddling the identities of these men. It would have helped if del Gesù had called himself “Joseph filius Joseph,” but we agree: that’s awkward. Nepos was the right choice; it wasn’t del Gesù’s fault that historians got it wrong.

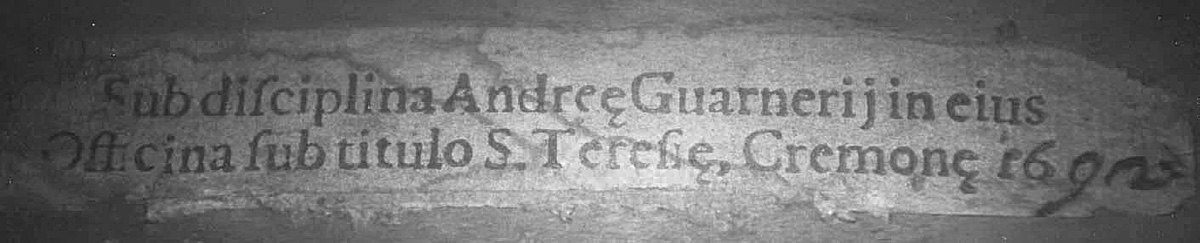

Del Gesù’s labels broke with another tradition too, one that his father, grandfather and uncle had followed for nearly eighty years. After Andrea Guarneri left the Amati workshop in the mid-1650s, his new independent label included four Latin words, “sub titulo Sanctæ Teresiæ.” This short phrase literally translates to “at the sign of Santa Teresa” but its meaning has been interpreted in different ways. We believe that the “sign of Santa Teresa” was a signpost, marker, symbol, statue or possibly an icon of Santa Teresa that was positioned on the façade of the Guarneri workshop to identify its location.

In one version of Andrea Guarneri’s label, used for instruments made under the master’s direction, the text specifies “in eius Officina sub titulo S. Teresię” (in his workshop at the sign of Santa Teresa).

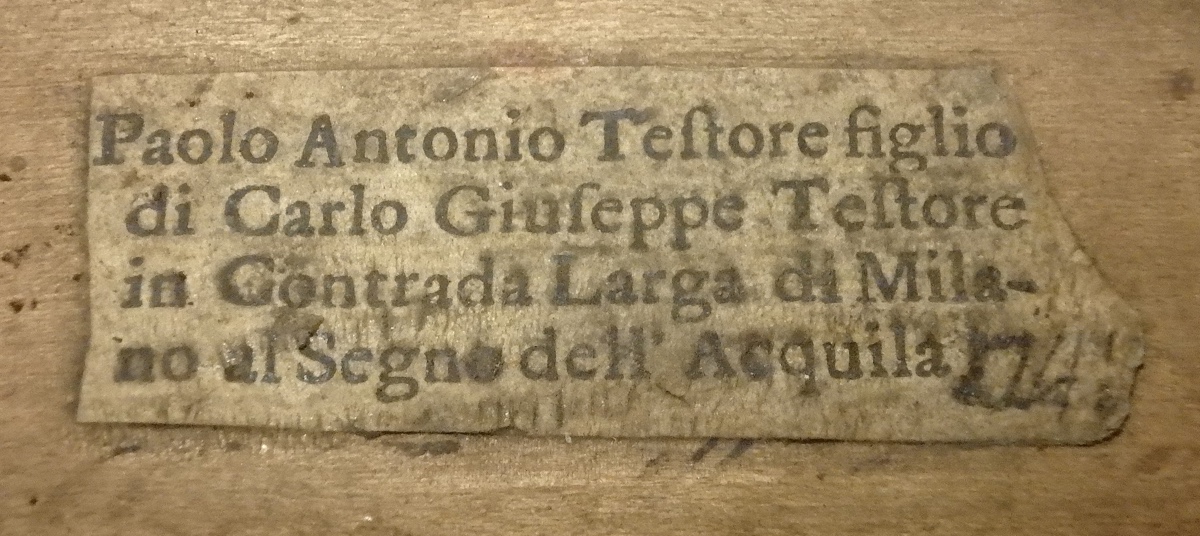

In Italy in the 18th century there wasn’t a precise or unified system for recording civic addresses. Few streets had names and houses rarely had numbers. Shops, inns, artisans and merchants commonly identified their location with a landmark that was distinctive and could be used by a traveler to locate the address they were looking for.

There were many examples of this in Milan, where the violin makers were clustered along the Contrada Larga, a wide boulevard in the center of town. Grancino, Testore and Lavazza all had their ateliers on this street and were in competition with each other. We can assume that Grancino didn’t want his customers to wander into the Lavazza workshop by mistake. As such, the Grancino family labels indicate “in Contrada Larga di Milano al segno della Corona” (in the Contrada Larga at the sign of the crown) whereas the Testore labels say “…al segno dell’ Aquila” (at the sign of the eagle). In the mid-18th century Landolfi suggested on his label that prospective customers come to the Contrada di Santa Margarita “al segno della Sirena” (at the sign of the mermaid), while his former pupil, Mantegazza, worked “al segno dell’Angelo” (at the sign of the Angel). Our favorite is the house where the Pasta and Grancino families lived for a time, which was an inn identified by “il cane che abbaia alla luna” (the dog barking at the moon). Similar locating phrases were used on makers’ labels in Venice, Florence, Bologna and elsewhere. The signs they referred to are long gone but would have helped customers locate a maker’s shop. Locals of all levels of literacy could direct a traveler to the violin maker at the sign of the eagle.

In this label from c. 1740, Paolo Antonio Testore referenced his father, Carlo Giuseppe, and gave his address “al Segno dell’Acquila” (at the sign of the eagle).

The first two generations of the Guarneri family worked in the Casa Guarneri in Piazza San Domenico, so it makes sense that Andrea and his sons Giuseppe and Pietro would have all used the “sub titulo” phrase on their labels while working there. After moving to Mantua in the mid-1680s, however, Pietro continued to use the “sub titulo” phrase. This may have been a symbolic way of asserting continuity and confirming that he was of the same clan as the Guarneris of Cremona, but it’s also possible that he replicated an actual sign of Santa Teresa outside his new workshop in Mantua. Pietro of Venice, on the other hand, the elder brother of del Gesù, didn’t mention Santa Teresa or any other address on his labels after he left Cremona around 1717. Del Gesù, who was last recorded in the Casa Guarneri in the census of 1722, never referenced Santa Teresa.

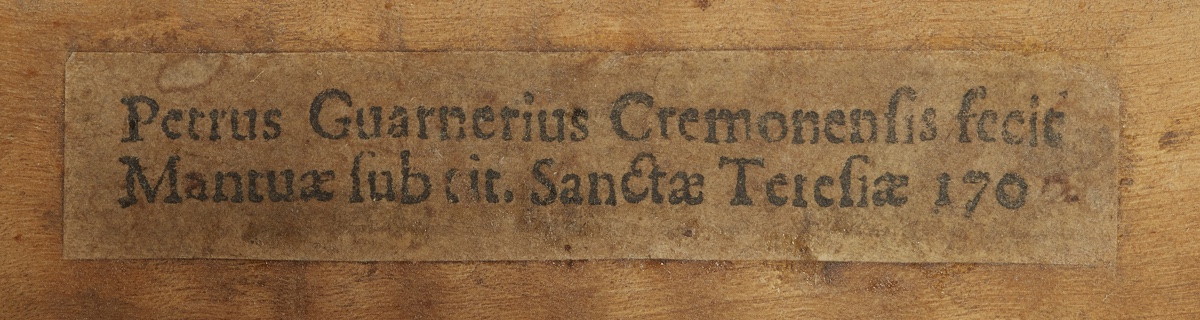

Pietro Guarneri continued to use the family’s ‘sub titulo’ phrase long after he had moved to Mantua. (Courtesy of Jan Strick, photo by Jan Röhrmann)

In or around 1731, several significant events occurred in del Gesù’s life: he moved into the center of Cremona and opened an independent workshop; his production increased considerably; and his father effectively retired from working following an illness. At this same time, del Gesù debuted a new version of his label, the type found in the ‘Baltic’, which he would use for the remainder of his career.

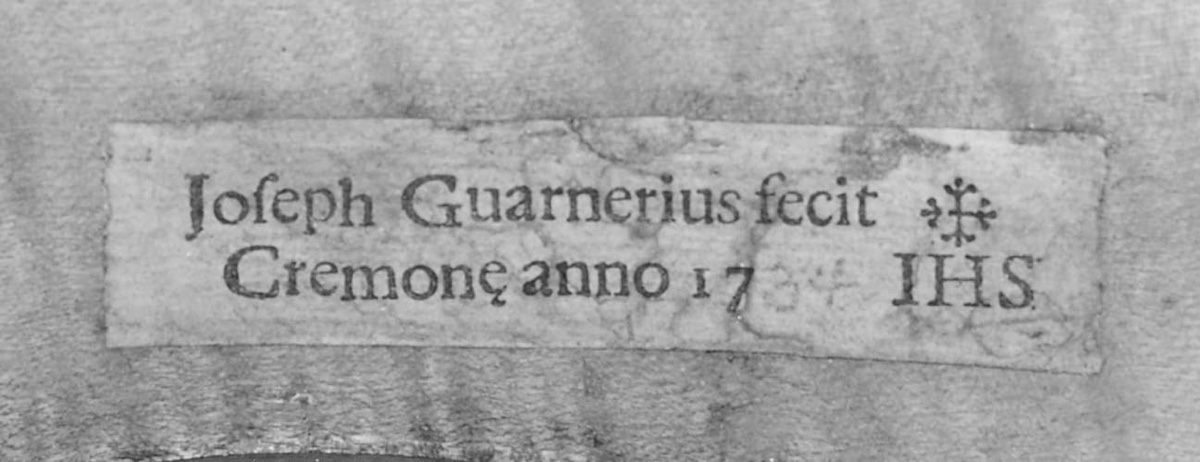

The label in the 1734 ‘Violon du Diable’. This new label format first appeared around 1731.

On this new label there was no ‘sub titulo’ phrase and there was no son of, grandson of, or nephew of clause. It was simply a bold, modern and confident label. What came to be its most distinguishing mark, however, more distinguishing perhaps than any other label in the history of violin making, were three printed letters at the far right side reading IHS. The initials are a Christogram derived from the first three letters of the Greek spelling of Jesus (ΙΗΣΟΥΣ). Since the 7th century, IHS had stood for the Latin motto, Iesus Hominum Salvator (“Jesus Savior of Mankind”), and by the 17th century, it had come to represent the order of Jesuits. These three letters — set under a cross but without punctuation or context — have provoked nearly three centuries of theories and speculation.

A conclusive explanation has yet to materialize but many interesting hypotheses have been suggested. Perhaps it was a symbol of a Jesuit connection. Or evidence of a pious artisan giving thanks to God. Or perhaps it was an imitation of the famous (A†S) monogram on Stradivari’s labels. Or, seeing how it first appeared around the time that del Gesù moved his workshop, the IHS seal could have referenced a sign or a landmark that helped customers find their way to his atelier. In the 18th century the IHS symbol was common and in fact the facades of many buildings in Cremona still bear this emblem as a decoration. Was there a conspicuous IHS sign near Guarneri’s new workshop? The answer may be simpler than it seems: In 1731 del Gesù no longer had to differentiate himself from his father; he needed to advertise his new address.

Whatever the explanation to this centuries-old riddle, we can take comfort in knowing that del Gesù’s new label was evidence of a new, independent and exciting chapter of the maker’s life.

Carlo Chiesa is a violin maker and expert in Milan; Jason Price is Tarisio’s Founder, Expert and Director.