The newly discovered record of the marriage of Antonio Gragnani del fu Onorato and Cecilia di Giuseppe Bianchi in 1751

Little has previously been known about the lives of the Tuscan violin makers, and recent archival research into this area has uncovered much valuable new information. In the town of Livorno we have found evidence of makers active since the end of the 16th century, and our findings have continued into the 18th century, including important documents relating to the Gragnani family.

We discovered that Antonio Gragnani actually had two sons, Giovanni Pietro and Filippo, and that the ‘son’ Onorato who is cited in past dictionaries was in fact Antonio’s father. We also found that Giovanni Pietro was recorded in various documents as a ‘chitarraio’ (a term that applied to makers of both plucked and bowed instruments, as today’s ‘liutaio’). Interestingly Antonio’s grandson (the son of Antonio’s daughter, Maria Elizabetta) Gaetano Bastogi was also a chitarraio. Such research has helped enormously to clarify the dating of instruments in the Gragnani family, such as the violin by Antonio featured here.

This 1775 violin is a beautiful reference example. Here the back (length 35.5 cm) is in one piece of handsome, slab-cut maple with horizontal flames. The table is in two pieces of spruce of medium-width grain. The ribs and scroll are of quarter-sawn maple of light, diagonal flame. The maker’s initials are branded externally on the button and on the table beneath the fingerboard, and the original label reads ‘Antonius Gragnani, fecit Liburni, anno 1775’.

The model is Gragnani’s own, though it bears features reminiscent of the Cremonese masters. The round upper and lower bouts are similar to Nicolò Amati’s Grand Pattern, although the C-bouts are shallower, more akin to Stradivari’s Amatisé pattern. Gragnani wasn’t afraid to make long, elegant corners, although in this example they are a little shorter than others.

The soundholes also loosely resemble the model of Nicolò Amati, although positioned slightly wider apart: they are upright, elegant and flowing, with circles that have been drilled out in the classic manner. The nicks are quite large (in the direction of Testore’s style) and the wings are kept flat. The full width of each ‘f’ is slightly narrower than those of Amati, more similar to those of Stradivari.

The arching is fairly full and a little square in appearance, bringing to mind the work of Tyrolese and other South German makers. Unlike Amati’s arching it has a full-bodied feel, due to the sudden rise up from the deep, medium-width channel to the wide, flat plateau. Gragnani’s high level of craftsmanship is clear when studying the violin in detail. The channel continues evenly around the body, even in the narrow area of the corner where the two channels meet from the bouts: this triangular area is tricky to execute, but Gragnani has left no evidence of the use of a different gouge or a triangular tool, as is often seen in other Italian makers’ work.

The side view reveals the idiosyncratic, vertically elongated shape of the scroll

The side view reveals the idiosyncratic, vertically elongated shape of the scroll. Unlike the makers of the Cremonese school, Gragnani gouged the volute’s turns leaving a rounded trench, which creates a hollowed-out look reminiscent of the German makers, rather than leaving them flat. The throat of the scroll is, typically for Gragnani, quite open under the chin of the volute. The front of the peg-box has a more pronounced tapered look than violins by most other makers, as the outside of the peg-box walls have been hollowed-out from the back chamfer towards the peg-holes.

Idiosyncrasies such as these are examples of a characterful maker. When compared with makers from other schools, Gragnani’s style is so individual that his work is superficially quite recognizable. Buyers should be aware, however, that this has made it easier for other makers to replicate his style.

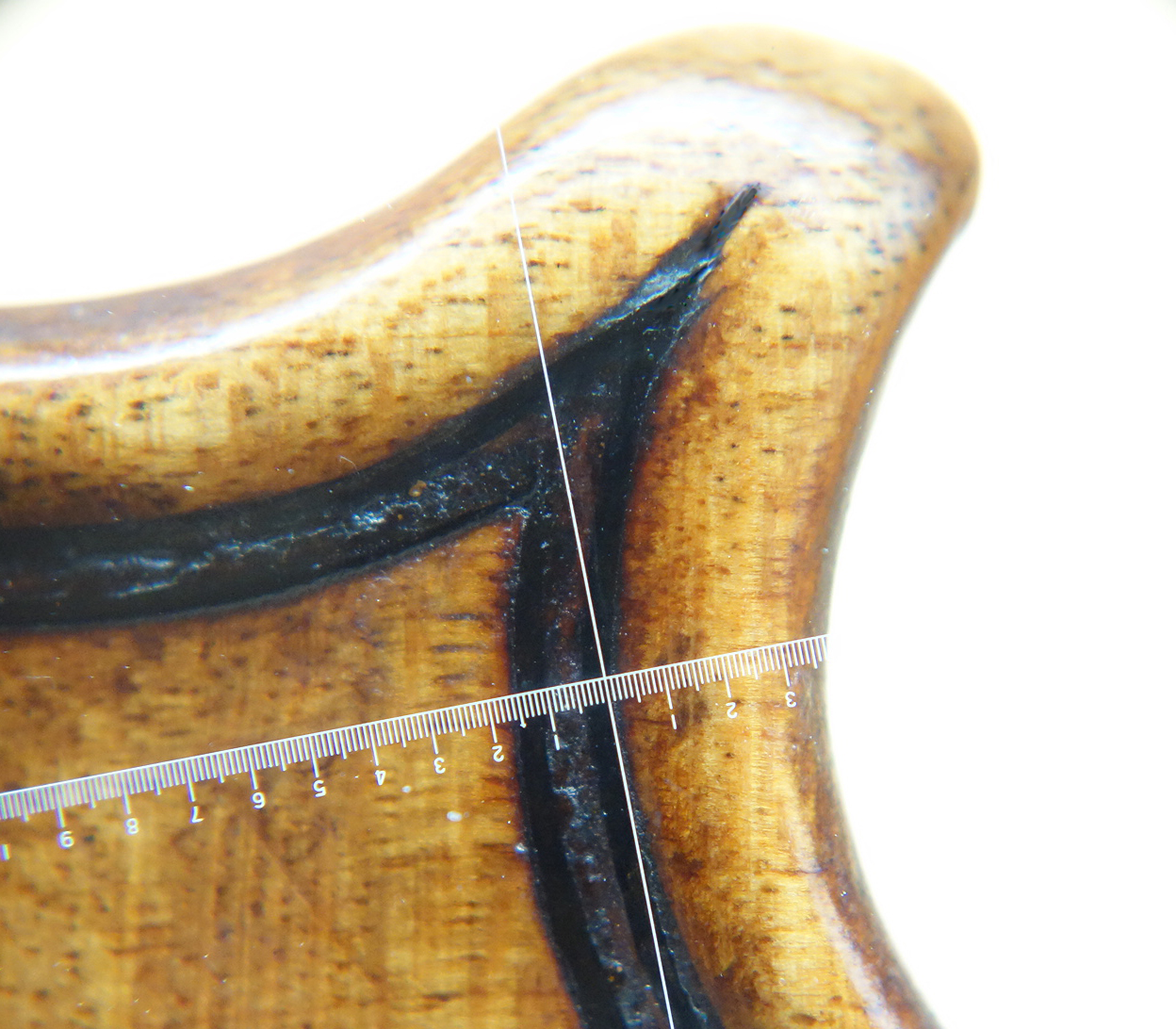

The lower bass corner. Gragnani often used whale-bone for his purfling blacks and beech for the whites

One interesting and beautiful Gragnani characteristic can be seen in the corners, particularly the lower bass corner, but also its diagonal opposite: here, the principal black of the purfling runs from the center bout without deviation, parallel to the edge and points uncompromisingly into the middle of the corner. The other black of the purfling, arriving from the lower bout, is clearly fitted to the leading black in the mitre. No bee-sting is present in any corner. Gragnani often used whale-bone for his purfling blacks and beech for the whites.

The corner of another Gragnani violin shows his care to place the purfling point directly in the center of each corner

It was Gragnani’s intention that both the outer blacks arrive from their respective bouts directly in the center of the corner in a point that is so sharp as to make its ending almost imperceptible. This feature was so important to him that when the point came accidentally into the inner third, Gragnani corrected it with mastics and lengthened the point into the center of the corner (as seen in the upper bass-side corner of the back of another of his violins, pictured above). This is not a unique instance of such a correction within Gragnani’s output.

Biographical information

Antonio Gragnani was born in Livorno on February 13, 1728, son of Onorato di Antonio Gragnani and Anna di Francesco Querci. He lived in the area of the parish of San Jacopo in Livorno, where his marriage to Cecilia Bianchi on October 21, 1751 is recorded. From this marriage two sons were born: Giovanni Pietro in 1765 and Filippo in 1768. The exact date of his death is unknown, but we do know that Antonio Gragnani was still alive at the time of the marriage of Giovanni Pietro to Maria Francesca di Domenico Olivero in 1792.

Expert Florian Leonhard, in conjunction with organologist Gabriele Rossi Rognoni of the Università di Firenze (SAGAS) and the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, is finalizing a book on the violin makers of Florence and the region of Tuscany. Extensive archival research has been carried out by Dott.ssa Maria da Gloria Leitao Venceslau in conjunction with Dott. Rossi Rognoni.