We remember Adolf Busch (1891–1952) as a violinist, but he also had a good deal to do with the viola: he performed on it as both soloist and chamber musician and wrote music for it. Most violinists, when they play the viola, have to use a smallish instrument and produce a modest tone. Busch was big enough in physique and had a sufficiently wide hand stretch to manage quite a large viola, such as the 1731 ‘Paganini’ Stradivari owned by his Berlin friends the Mendelssohns, on which he several times performed Harold in Italy. Another viola he occasionally played was a composite instrument belonging to the Viennese collector Wilhelm Kux, which had begun life as a Stradivari viola d’amore. [1]

Adolf Busch. Photo: Tully Potter Collection

Throughout his career, Busch owned violas: his father Wilhelm made him at least two; his father-in-law Hugo Grüters gave him one; he bought an excellent 1783 Giovanni Battista Guadagnini; and in 1934 Fritz Baumgartner built him an instrument to order. [2] That year he also purchased a Vincenzo Panormo for £103 which was used by his longtime pupil Dea Gombrich [3] – he had earlier chosen her violin, a Carlo Tononi. He was planning to start his conductorless orchestra, the Busch Chamber Players, and he wanted Gombrich to play viola as well as violin: we can hear her playing second viola on the Panormo in the one-to-a-part performance of Bach’s ‘Brandenburg’ Concerto no. 3 recorded by the Chamber Players in 1935.

Busch even kept a viola pomposa, constructed by his father, and played it occasionally. [4] His training at the Cologne Conservatory included a certain amount of viola playing and he appeared several times as violist of the Gürzenich Quartet. But those were the days when German orchestral musicians called the Bratsche the ‘Penzioninstrument’, as William Primrose pointed out: ‘When considered too old, too decrepit, or too immoral to play the violin… the violinist was relegated to scrape out the winter of his discontent as a violist.’ [5]

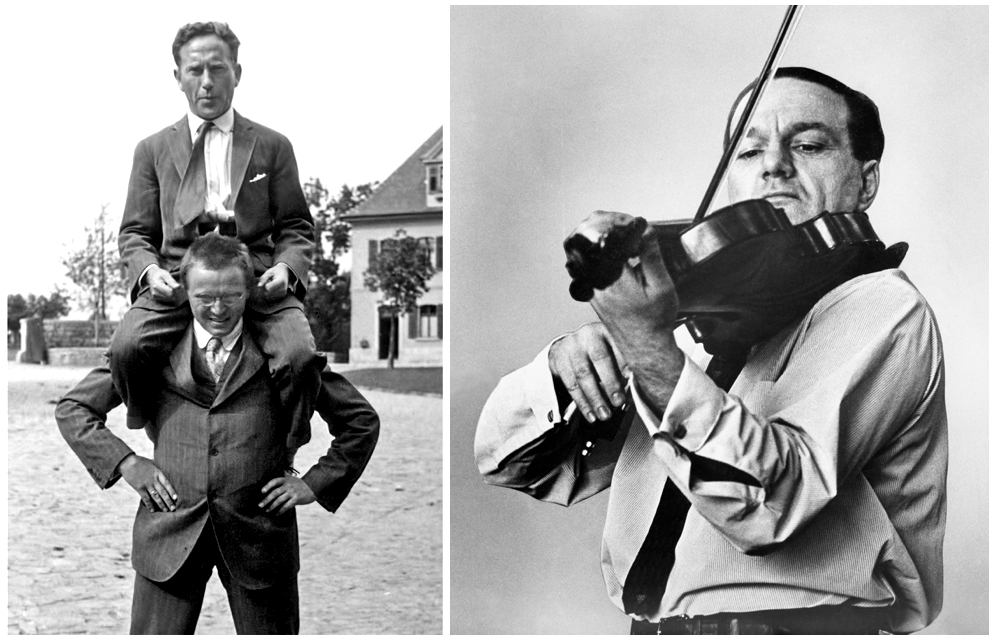

Left: Adolf Busch and Karl Doktor in 1929. Right: Paul Doktor, son of Karl. Photos: Tully Potter Collection

To an extent, Busch shared this view. ‘Only lazy violinists play the viola’ he would say, and he displayed a casual attitude in his choice of violists. As often as not, he would play quintets with a violinist, such as Fritz Hirt, on the second viola. Or a friend who had hardly held a viola in his hands would be pressed into service as second violist, such as Moryc Cybula, who had one week in which to rehearse all six Mozart Quintets with the Busch Quartet. A similar incident launched Karl Doktor’s son Paul on his career as a violist, when he had just fled Vienna in 1938. ‘Shortly after my arrival in Switzerland,’ Paul Doktor recalled, ‘Busch planned a benefit concert for German and Austrian refugee children, pointing this out in his programme by choosing Schubert’s two-cello Quintet and Mendelssohn’s first two-viola Quintet. Just a week before the concert, the second violist came to Busch explaining that he was so nervous, he didn’t think he could play that Mendelssohn Quintet. Busch quietly took the music back from the young man and said: “Thank you for telling me today instead of later” – and turning to me and handing me the music, continued casually: “Here, Paul – practise!” I was dumbfounded, but I went and practised.’ [6]

Violinist Philipp Naegele recalled how he was drafted in as a last-minute replacement for the very last concert of the Busch Quartet in 1951: ‘“But I don’t have a viola!” I said. “Oh, I have one my father made fifty years ago,” said Adolf Busch unapologetically. He handed me a heavy, red-varnished viola, which […] put me at a serious disadvantage in the serene company of the Stradivarius, Guadagnini, and Goffriller instruments of my awe-inspiring colleagues. I remonstrated meekly. A modern viola was borrowed from the kindly Swiss luthier Karl Berger in New York. […] That Adolf Busch, the owner of an unforgettably pure and paternal sonority on the violin, a sound ideal for the “Benedictus” of Beethoven’s Missa solemnis, could have seriously expected me to manage with that red box was really quite in line with an old, established prejudice that relegated the viola to secondary status in all respects. Any violinist, even a young guy like me who hadn’t touched a viola since high school, was supposed to be qualified to take over a viola part any time. A little more spread in the hand, a little more of a reach with the bow, some quick clef thinking, and an appropriately subaltern disposition were all that was needed.’ [7]

‘Any violinist, even a young guy like me who hadn’t touched a viola since high school, was supposed to be qualified to take over a viola part’ – Philipp Naegele

When Busch needed a violist for his re-formed Quartet after World War II, he chose Hugo Gottesmann, a violinist. The only specialist violists in his circle were Karl Reitz, Philipp Haass, Albert Bertschmann and Gottesmann’s predecessors, Karl Doktor and Lotte Hammerschlag. When Fred Gaisberg of HMV proposed Brahms’s F major Quintet op. 88 for recording in 1932, Busch’s secretary replied: ‘It is of course not possible to perform this piece, as Professor Busch has not got a second viola-player.’ [8] Ironically, when such a player – Paul Doktor – was at last available in 1939 and quintet recordings could be scheduled, the war intervened.

Left: the Busch Quartet in 1947 (from left: Busch, Bruno Straumann, Herman Busch, Hugo Gottesmann). Right: the same line-up, which lasted from 1947 to 1951. Photos: Tully Potter Collection

Like Milstein and David Oistrakh, Busch was a Stradivari man, so it was not surprising that his favourite viola was the ‘Paganini’ Strad in Robert von Mendelssohn’s collection. By the time he came to know the family in Berlin at the end of 1919, Robert was dead, but he made music with Giulietta von Mendelssohn, a fine pianist, and her son Francesco often served as second cellist with the Busch Quartet. Busch must have played the ‘Paganini’ viola at the family’s home, but his main engagement with it was as his preferred instrument for Harold in Italy.

As for his violins, he began his career in 1910 using one made by his father, but by 1913 was borrowing a Strad and that year acquired the 1716 Stradivari that now bears his name. In 1925 he bought the 1732 ‘Wiener’ Stradivari for 65,000 marks from his Viennese friend Dr Paul Hellmann and it became his main instrument. [9] When he halved his income by boycotting his native Germany from 1933, he had to sell the 1716 Strad but ordered a copy of it from Fritz Baumgartner to go in his double case. [10] Busch’s other favourite maker was G.B. Guadagnini and he owned several violins as well as the viola mentioned above.

Busch’s somewhat cavalier attitude towards the viola was typical of an era when it was generally thought to be unwieldy and difficult to play in tune. He was well advanced in his career by the time the virtuosity of such players as Oskar Nedbal, Lionel Tertis and Maurice Vieux began to have an effect on the profession as a whole, and thus performances by both the Busch Quartet and his Chamber Players suffered slightly from underplaying of the inner parts: Busch chose violists – and second violinists – more for their musicality and their ability to fit in, than for their power.

In 1910 one critic commented on the ‘unusually noble viola-like sonority’ of Busch’s violin

Yet he was perhaps more deeply influenced by viola tone than he realised. After Busch’s Dresden debut in 1910, a critic commented on the ‘unusually noble viola-like sonority of his instrument’ [11] and in reviewing some of his American recordings 68 years later, Harris Goldsmith emphasised that ‘even at its most abrasive, the sound had a remarkable alto quality virtually extinct among violinists today’. [12] Sometimes, when listening to a Busch Quartet recording, one has to be following the score to be sure that it is the leader, not the violist, who is playing.

Busch often took up the viola in Hausmusik. ‘When Adolf played the viola it sounded marvellous,’ his sister-in-law Lotte Busch said. [13] Apart from the Sixth ‘Brandenburg’ Concerto and Harold in Italy, his repertoire included Brahms’s Zwei Lieder and Wolf’s Italian Serenade in Reger’s arrangement with solo viola. And he composed a significant amount of music for the viola, including an alternative version of the Nocturne on a Negro Spiritual op. 58a, [14] and two solo works: the delightful Suite in A minor op. 16a, written for Karl Doktor and the Prelude and Fugato in E minor BoO 6, for Hugo Gottesmann. [15] Busch’s chamber compositions often incorporate rewarding parts for the violist, and viola tone strongly colors his late masterpiece, the Flute Quintet in C major op. 68 – two viole da braccio are employed. When he himself played it, he took the first viola part.

To sum up, it is clear that, despite his occasionally blasé attitude, Busch loved the viola and its plangent sonority – which fitted so well with his own tone.

Music critic Tully Potter is the biographer of Adolf Busch and a regular contributor to various international music journals.

Read Jason Price’s commentary on the Busch Vincenzo Panormo viola, currently available in our private sales department.

Notes

[1] It is thought that the brothers Antonio and Girolamo Amati replaced the original cherub’s head with a scroll in converting this instrument from 12 strings to four, and that J.B. Vuillaume replaced the flat back with a curved one.

[2] This viola, Baumgartner’s ‘Opus 120’, had a body length of only 39.7 cm, so Busch may have envisaged one of his female students using it in the Chamber Players.

[3] Anna Amadea Gombrich (Lady Forsdyke) was the eldest child of Busch’s Viennese friends Karl and Leonie Gombrich and sister of the art historian Sir Ernst Gombrich. A founder member of Bronislaw Huberman’s Palestine Orchestra, after the war she became a music therapist and married Sir John Forsdyke of the British Museum.

[4] Normally this instrument would be played (and strung) cello-fashion; but because Busch was such a big man and had such a long neck, he was able to hold it under the chin.

[5] William Primrose and David Dalton, Walk on the North Side: Memoirs of a Violist, Brigham Young University Press, Provo, Utah, 1978, pp. 19–20.

[6] Letter to the author, dated April 11, 1977.

[7] Philipp Naegele, In the Studio: Viola Musings, Journal of the American Viola Society, vol. 22, no. 1, Spring 2006, pp. 24–25.

[8] Letter dated September 6, 1932 (EMI Archives).

[9] This violin was named after a former owner, Wilhelm Wiener, rather than Vienna.

[10] This violin, Baumgartner’s ‘Opus 128’ of 1936, came in handy when Busch had to play in hot climates, as on his 1936–37 tour of Greece, Palestine and Egypt.

[11] Dresdner Neueste Nachrichten, November 11, 1910.

[12] High Fidelity, vol. 28, no. 6, June 1978, p. 106.

[13] Interview with the author, 1980.

[14] Originally for saxophone and chamber orchestra.

[15] This piece, kept by Gottesmann for his own enjoyment, came to light only after his death.