There are only ten complete Stradivari violas in existence and they are arguably the rarest and most valuable stringed instruments in the world. These don’t change hands often, so when they do, it tends to be a big deal. This week, it gives me great pleasure to announce that the 1690 ‘Tuscan, Medici’ Stradivari viola has been gifted to the Library of Congress by David and Amy Fulton and the family of Cameron Baird. This is a gesture of extraordinary philanthropy and ensures that the public will hear and experience the ‘Tuscan, Medici‘ for generations to come.

Nearly fifty years ago, the ‘Tuscan, Medici’ was placed with the Library on an indefinite loan by the widow of entrepreneur, philanthropist and music educator Cameron Baird. A devoted pianist, violist, and conductor, Baird helped establish the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra and was the first Chairman of the Music Department at the University of Buffalo. He had a deep interest in string instruments, and although the ‘Tuscan, Medici’ was one of the last instruments he acquired, it was the pinnacle of his collection. Due to an extended illness, Baird was unable to play the ‘Tuscan, Medici’ for long and decided instead to loan it to Boris Kroyt of the Budapest Quartet. The quartet had a close relationship with the Library of Congress and were frequent performers in the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium. Following Baird’s death in 1960, his wife, Jane, formally loaned the ‘Tuscan, Medici’ to the Library in 1977.

The Budapest String Quartet in c. 1960 when Boris Kroyt had loan of the ‘Tuscan, Medici’ viola. From left: Mischa Schneider, cello; Boris Kroyt, viola; Alexander Schneider, second violin; and Josef Roisman, first violin.

Nearly fifty years later, the Baird family loan has been made permanent by a gift from the Fultons. Arguably the greatest American collector of musical instruments of his generation, David Fulton started his career as a computer scientist and mathematician. In the 1970s, he developed the FoxPro database management system, which he later sold to Microsoft. At its height, his collection included some of the world’s most important 17th and 18th century Italian instruments, but it lacked one important thing: a Stradivari viola.

Aside from their rarity, what makes a Stradivari viola so important? Like his violas and cellos, Stradivari’s violas are sublime achievements of craftsmanship and art. They also have been companions to some of music history’s most important moments, for instance, Hector Berlioz’s Harold in Italy which was written with the 1731 ‘Paganini’ Stradivari in mind. But perhaps the greatest allure of a Stradivari viola is that it is the key to unlocking what Fulton himself referred to as the “collectors’ Holy Grail” and the “ultimate achievement,” that is, owning a Stradivari quartet.

The acquisition of the ‘Tuscan, Medici’ means that there is now only one Stradivari viola left in private circulation, the 1719 ‘MacDonald.’

Throughout history, very few collectors have managed to assemble a complete Stradivari quartet. I count only thirty-eight owners and institutions who have had two violins, a viola and a cello by Stradivari at any one moment over the past 350 years. (At the end of this article you’ll find a list.) Fulton himself tried five times to acquire a Stradivari viola but never managed to get one. The acquisition of the ‘Tuscan, Medici’ means that there is now only one Stradivari viola left in private circulation, the 1719 ‘MacDonald.’

![]()

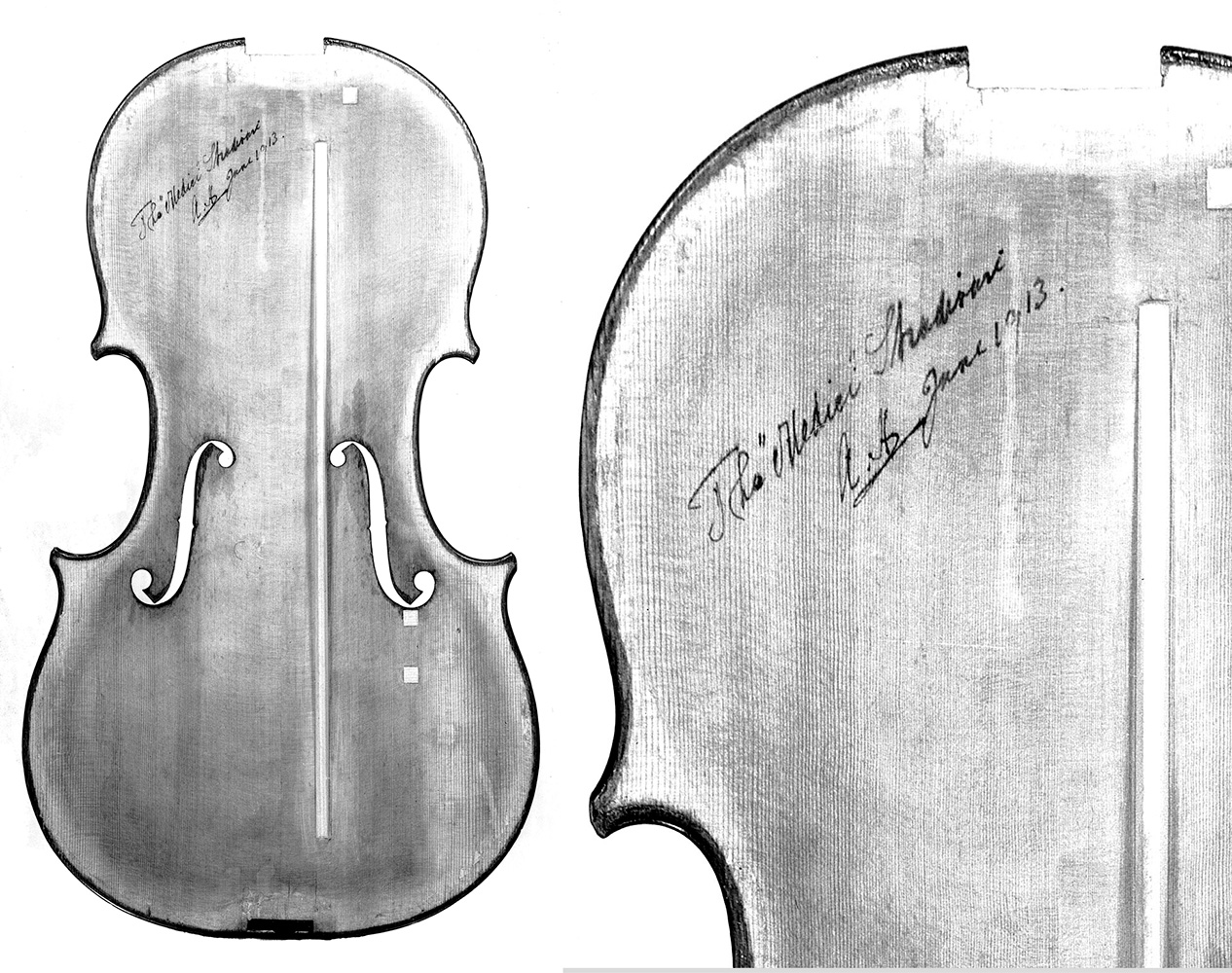

The ‘Tuscan, Medici’ was made in 1690 to complete a set of instruments commissioned by the Cremonese nobleman Bartolomeo Ariberti and gifted to Ferdinando de’ Medici, the Grand Prince of Tuscany. I find it very meaningful that this viola was inspired by a gift in 1690, and is again a gift today. Philanthropy and patronage have always played a special part in musical – and instrument – culture. Long may that continue.

I find it very meaningful that this viola was inspired by a gift in 1690, and is again a gift today. Philanthropy and patronage have always played a special part in musical – and instrument – culture. Long may that continue.

Grand Prince Ferdinando de’ Medici (second from right) and his musicians, by Anton Domenico Gabbiani. Galleria dell’ Accademia, Florence

My colleague Alessandra Barabaschi wrote a comprehensive, three-part history of the Medici commission as a Carteggio in 2015. The summary is this: Ariberti was a wealthy Cremonese aristocrat and devoted admirer of Stradivari. In 1690, he ordered a set of instruments from Stradivari to be presented to the Grand Prince Ferdinando de’ Medici in Florence, an accomplished musician and an influential patron of music. The original commission consisted of two violins and a cello—the elements of the popular trio sonata—and they were so well received by the Prince that Stradivari was asked to complete the set with two violas: a large tenore and a smaller contralto.

The commission of the Medici violas was an important milestone in Stradivari’s career which inspired him to develop two entirely new viola models. In the artifacts preserved in the Museo del Violino in Cremona, we find Stradivari’s original paper patterns and the molds that he used to make these two violas. In Stradivari’s handwriting we find the inscription “..contrato [sic] fatto ha [sic] posto per il Gran Principe di Toscana” (contralto expressly made for the Grand Prince of Tuscany). The new contralto model was evidently a big success for Stradivari because he continued to use that model for the next forty-five years, making all his remaining violas on the same mould. The tenore viola is the only one of its kind that was made, or at least, the only one that has survived. It is preserved in Florence in the Istituto Cherubini and is in a remarkable state of preservation, still retaining its original neck, fingerboard, pegs, bridge, tailpiece and end-button. We can assume that the ‘Tuscan, Medici’ contralto was originally fitted with similar decorations.