The Hofmans family were the most important instrument makers in Antwerp for over two centuries. They were already active in instrument making by the 16th century, as we can see from a document dated 11 October 1538. It is a formal demand from Jan Hofmans, asking the city’s customs for permission to recover the tools of his son Hans Hofmans, who had died that year in Danzig (Gdansk). The fact that Hofmans had sent his son to work in Danzig, far away on the Baltic coast, gives a picture of an entrepreneurial family successfully established in violin making and able to experiment with expansion. The Hofmans were, moreover, members of the St Lucas Guild in Antwerp, which was largely used by artists and a step up from the St Job Guild used by the speelmannen – musicians hired to play in bars or at parties – and the instrument makers who served them.

![]()

Little is known about the Hofmans, and until research by the musicologist Godelieve Spiessens was published in 2009 (‘Bulletin des Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire – Parc du Cinquantenaire Bruxelles’ Tome 80) it was thought that there were perhaps two different Hofmans makers, as the style of their instruments roughly divides into ‘old’ and ‘new’. In fact, as Spiessens showed, there were over five generations of Hofmans makers and probably more than ten of them were active in the city between 1500 and 1740. Confusingly, Matthijs was the most common first name for the family’s makers and most of the original labels are undated, so it is often difficult to identify which Matthijs made a particular violin, especially as they all used the same model.

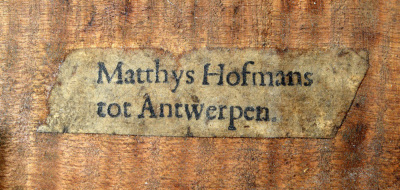

The violin featured here is in the ‘old’ Hofmans style and was probably made by Matthijs Hofmans III (1594–1675), the earliest family member from whom violins still exist. It dates from around 1650 and was possibly made in collaboration with his son, Matthijs Hofmans IV. The label reads: ‘Matthys Hofmans, tot Antwerpen’. It is made in the typical tradition of 17th-century Flemish violins, which stretched from Antwerp via Paris to Genova in northern Italy. The ribs are set in a channel in the back, while the neck and the upper block are in one piece (see more information on the construction methods of the Flemish school below).

Most original Hofmans labels are undated

Stylistically Hofmans instruments are influenced by an early 17th-century model used by the Brothers Amati but tend to be larger than the Italian originals, which can benefit the sound. It is not clear whether this influence was the result of direct connections between makers in Cremona and Antwerp, or if the Flemish craftsmen simply copied Italian instruments brought to them by musicians, but the larger size (a typical Flemish violin from this period tends to have a back length of around 35.6 cm) suggests that they were copying the Italian instruments by drawing round the outline. Supporting this theory is a letter from 1624 that refers to four Cremonese violins bought by Philippe-Charles, Duc d’Arenberg, one of the most powerful of the Spanish Netherlands nobility, so it is plausible that the Hofmans would have seen original Cremonese violins.

The purfling is probably dyed maple, with the central strip left a natural color

The f-holes of this violin are clearly inspired by the Amati style. The scroll has a very personal style and could be described as having a swan-neck shape, which is typical for the Hofmans family. The outer and inner purfling strips are both probably maple, with the dark strips dyed and the central strip left a natural color. Hofmans instruments tend to be very well made, with craftsmanship of a high standard and an oil varnish that is somewhere between Venetian and Cremonese in quality.

The ‘swan neck’ of the scroll is very typical

The wood of Hofmans instruments varies in quality from a very simple but well-chosen local maple seen in this violin to a fantastic Balkan maple. Dendrochronology has shown that contemporary Flemish paintings were painted on wood imported from the Balkans, and presumably violin makers had access to the same sources of wood. The spruce is similar to the wood from Hamburg that passed through Amsterdam to the Flemish makers.

The Flemish style of violin making ceased around 1740, almost at the same time as the decline of the great Cremonese school. At that time a new style of violins was arriving from France, along with an influx of French makers fleeing unrest in their country. The Flemish makers adopted the French style and the old tradition came to an end.

***

Construction methods of the Flemish school

Unlike the classical Cremonese school, the Flemish makers did not share a uniform approach to their craft, and various different construction methods can be seen in their instruments.

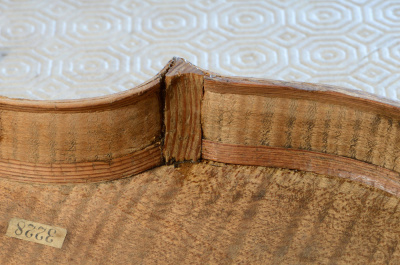

The linings and corner blocks were added after the ribs were glued to the back

The inside of the back has a channel around the edge in which the ribs are set. In Flemish violins this channel is made in different ways, depending on the maker. Sometimes both sides of the channel are cut straight and perpendicular to the back; sometimes only the outside is straight and the inside is cut at an angle (both these methods were applied by the Hofmans family). This way, the ribs slide exactly into the right position when they are set and glued to the back. The linings and corner blocks are added only after the ribs are glued to the back. At this point the corner blocks still have a square shape and the gluing side of the linings has small notches in order to make it bend more easily. After the linings are glued, the excess wood is removed, probably by scraping it out, and eventually the linings are fluted so they have a hollow shape. Pine wood is generally used for the linings and corner blocks. The upper linings are made in a more traditional way and they are also narrower than the linings of the back. Some instruments, however, were made without linings.

Before 1740 all Flemish instruments had a neck and upper block made of one piece. The neck block is much narrower than a classic neck block, and is also longer, so a platform on the inside back is needed to support the neck block.

Violin maker and expert Jan Strick specializes in the study of Flemish school instruments.