New York has always attracted the best and the brightest. But it also attracts its fair share of troublemakers so it comes as no surprise to learn that New York’s first documented violin maker was a convicted felon who died in a botched robbery attempt. Geoffrey Stafford came to America from England around 1690 and settled in Massachusetts. He was conscripted and sent to fight the indigenous populations in the Albany territories in northern New York where he met and befriended the Royal Governor of New York, Benjamin Fletcher.[1] That a governor and a convicted felon could become friends was as extraordinary as it sounds, but perhaps the relationship flourished owing to Fletcher’s own notoriously unscrupulous record. During his administration, New York had become somewhat of a safe haven for outlaws and criminals. Stafford and Fletcher got along so well that Fletcher brought him to New York City. There are records of Stafford making violins in New York in the early 1700s, although no known examples survive today.[2]

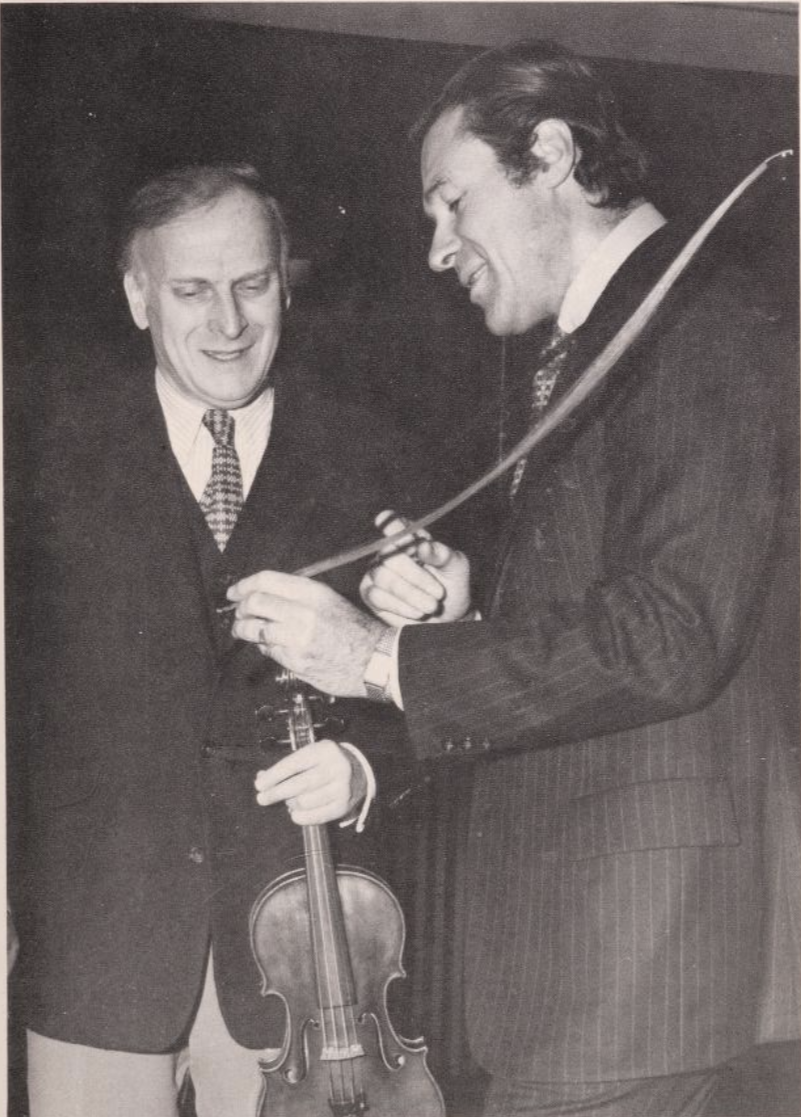

Jacques Français showing Yehudi Menuhin a bow made by Tourte and owned by Thomas Jefferson.

Stafford’s time in New York was cut short after he murdered Fletcher’s valet. Exiled from the city, Stafford took to the road again. Some time later he was involved in a failed robbery attempt and was hanged by his would-be victim.[3]

By the mid-18th century, Robert Horne had settled in New York. A viola by Horne dating from 1757 is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and is considered to be the oldest surviving violin family instrument made in the United States. Horne was proficient on a wide range of instruments and services. An advertisement appearing in the New-York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury newspapers in 1772 offered: “Violins, tennors, violon-cellos, guittars, kitts, aeolus harps, spinnets, and spinnets jacks, violin bows, tail-pieces, pins, bridges; bows hair’d, and the best Roman Strings.”[4]

A viola by Robert Horne, New York, 1757, Metropolitan Museum of Art

By the end of the 18th century, several other luthiers had established themselves in the city. In 1789 Thomas Dodds, a harpsichord maker with no relation to the English instrument and bow making family, sold a harpsichord to President George Washington. In the early 19th century, a violin maker from Boston, Paul Lamson, was advertising his services in New York. In 1818, Nicolas Antoine Lété of Mirecourt established a musical instrument import business. By 1820, Lété had returned to France where he hired a young violin maker named Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume.

Claude Augustin Miremont spent a decade in New York from 1852 to 1861.

Over the course of the 19th century, many makers from France and Germany immigrated to New York City: Charles Mercier settled there in 1840; Mattias Sprenger immigrated in 1846 and opened his shop in 1849; George Gemünder came to New York in 1847; John Strodl maintained a shop in New York City between 1852 and 1880; and Claude Augustin Miremont worked in New York between 1852 and 1861. Gemünder, Miremont and Strodl all entered instruments in the New York Exposition of 1853-54. Miremont and Gemünder were awarded medals but it was Gemünder who soon became New York’s preeminent violin maker.[5]

The New York Crystal Palace, where the 1853-54 exhibition was held.

The Gemünder family

Born in 1816 in Ingelfingen, Germany, George Gemünder first trained under his father and later went to work for Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume in Paris. George’s brothers, August Martin Ludwig and Albert, were also involved in the instrument trade and by the mid 1840s they were running an organ shop in Springfield, Massachusetts. August and Albert convinced their brother to join them in America and he arrived in 1847.[6] The Gemünder brothers formed a traveling quartet composed of clarinet, flute, bass guitar and violin.[7] When their musical career failed to take off, George moved to New York City to open a violin shop in 1850.

At a time when his contemporaries regularly imported tonewood from Europe, Gemünder often utilized American sugar maple and once even made a violin out of spruce reclaimed from the joists of a demolished Manhattan church. The catalog to the 1853-54 New York Exposition noted that the instruments Gemünder submitted were made with “American materials, except for the strings.”[8]

After Gemünder was awarded the first prize in London’s Great Exhibition, Ole Bull, the Norwegian soloist noted, “Now you shall become in America what Vuillaume is in Europe.

A postcard from George Gemünder to his “friend F. (Francis) Wayland-Smith”, sent from his 949 Broadway Address on December 16, 1892. Smith was a violinist living in Oneida, New York, and the principal violinist of the community orchestra for the sect of Christian Perfectionists that would found the tableware manufacturing giant Oneida Limited.

With his training in the Vuillaume workshop and having won prestigious awards from the London and New York world’s fairs, George Gemünder quickly became one of the most important makers, not only in New York, but in the entire United States. After Gemünder was awarded the first prize in London’s Great Exhibition, Ole Bull, the Norwegian soloist noted, “Now you shall become in America what Vuillaume is in Europe.”[9]

In 1859, Gemünder’s brothers joined him in New York. Albert continued to work as an organ builder. August’s output of violin family instruments grew to rival Gemünder’s and notably, he was significantly better at business. For the next fifteen years, the Gemünder family worked side by side in Manhattan. George had three sons, George Jr., Hermann Ludwig and Otto. August also had three sons, August Martin, Rudolf Frederick and Oscar.

In 1874, George Gemünder moved his workshop to Astoria, Queens. At that time, Astoria was only accessible from Manhattan by ferry and this move caused George’s business to suffer. August’s business in Manhattan, on the other hand, continued to thrive. Seeing his brother’s booming business, George re-opened a shop in Manhattan in 1886 and called it George Gemünder & Sons. Following suit, August changed his firm’s name to August Gemünder & Sons four years later.

In 1889, George Sr. suffered a stroke and his sons took over operations of the workshop. George passed away a decade later in 1899. Two years later Otto died at the age of 30. His obituary, which appeared on June 13 in The New York Times noted that, “up until his death in Astoria two years ago, Otto Gemünder was his [father’s] constant companion.”[10] Hermann died in 1912, followed by George Jr. who died bankrupt in 1915. The family firm George Gemünder & Sons closed that same year.

August Gemünder died in 1895 and his sons continued the workshop. August Gemünder & Sons continued in business until 1946.

A rare label from Gemünder’s time in Boston.

More makers

Henry Richard Knopf was born into a family of German bowmakers. He trained with his father in Berlin and his uncle in Dresden before immigrating to America in 1879 where he went by the name “Henry”. He worked first in Philadelphia before moving to New York City in 1880. He made bows and instruments and developed a prolific workshop before passing it to his sons upon his retirement in 1930.

Another bow maker, Edward Tubbs, landed in New York the same year that Knopf arrived in Philadelphia. From the famous family of English violin and bow makers, Tubbs also established a successful instrument import business.

John and William Friedrich immigrated from Germany and opened the John Friedrich & Brother firm in 1883. William was a musician, and John is credited with building over 300 instruments for which he won prizes at expositions in Chicago (1893), St. Louis (1904) and Philadelphia (1926).

Other European makers would find their way to the city, and the German and French schools of violin making would dominate until the arrival of Simone Fernando Sacconi in 1931.

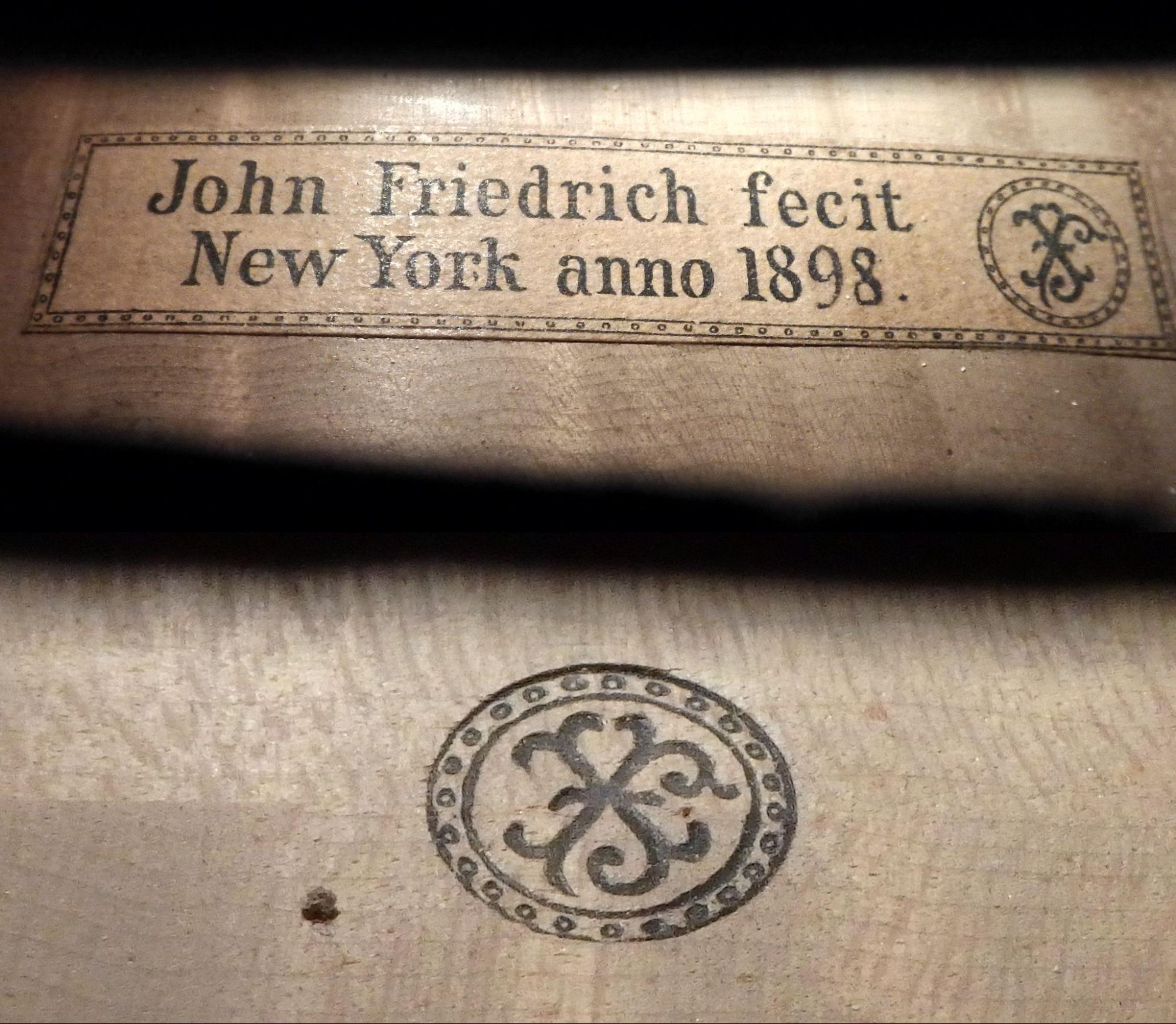

John Friedrich’s label together with his insignia J & F.

A rapid development

The number of violin makers and shops in New York expanded dramatically during the late 19th century due in part to the city’s new status as a major international economic player. By the turn of the 20th century, New York had surpassed London as the wealthiest city in the world and with this newfound economic dominance came a desire for European art and culture.

Rudolph Wurlitzer and Emil Herrmann were both violin makers of German descent. Wurlitzer’s father established the Wurlitzer Company in Cincinnati in 1853. Herrmann’s father was a maker and dealer in Berlin. In 1909 Rudolph Wurltizer opened a shop in New York specializing in antique European instruments. Herrmann established his New York shop in 1924. Two years later he immigrated, and five years after that, he brought the Italian violin maker Simone Sacconi to be his chief restorer.[11]

Sacconi was born in Rome on May 30, 1895. His father, Gespare, was a violinist and the concertmaster of a small community orchestra. As a teenager, Sacconi studied first under Giuseppe Rossi and then Giuseppe Fiorini. In 1928 Sacconi met Herrmann, who offered him a one-year position in his workshop in Berlin. Sacconi quickly advanced to the position of chief restorer, and immigrated to America in 1931 to run Herrmann’s rapidly-growing firm.

Over the course of the next half-century, Sacconi became arguably the greatest influence on violin making in the United States. He worked for Herrmann until 1951 and then went to work for Rembert Wurlitzer, Rudolph’s son. In addition to the thousands of instruments that he repaired and restored, Sacconi made around a hundred instruments himself, some of which were bench copies of historical instruments. He also wrote a highly influential treatise on violin making “The Secrets of Stradivari” and taught at the International School of Violin Making in Cremona. Most importantly, Sacconi trained a generation of American makers and restorers. Among his apprentices and colleagues, Sacconi can count Max Möller, Erwin Hertel, Dario D’Attili, Hans Weishaar, Mario D’Allessandro, Frank Passa, René Morel, Bill Salchow, Hans Nebel, Vahakn Nigogosian, Charles Beare, Daniel Antoun, Luiz Bellini, Frank Torres, Jamie Salamanca, Carlos Arcieri, Sadanori Kasakawa, Christine Bischoff, Robert Cauer, Roland Feller, William Webster, David Segal and many others.

Born in the Brazilian countryside just outside of São Paulo, Luiz Bellini arrived in New York City in November of 1960 to work under Sacconi at Wurlitzers. Bellini spent his first two years learning restoration and eventually began making bench copies of the historical instruments that passed through Wurlitzers. His instruments drew the attention of Yehudi Menuhin, Gidon Kremer, David Nadien, Glenn Dicterow, Ruggiero Ricci and many others.

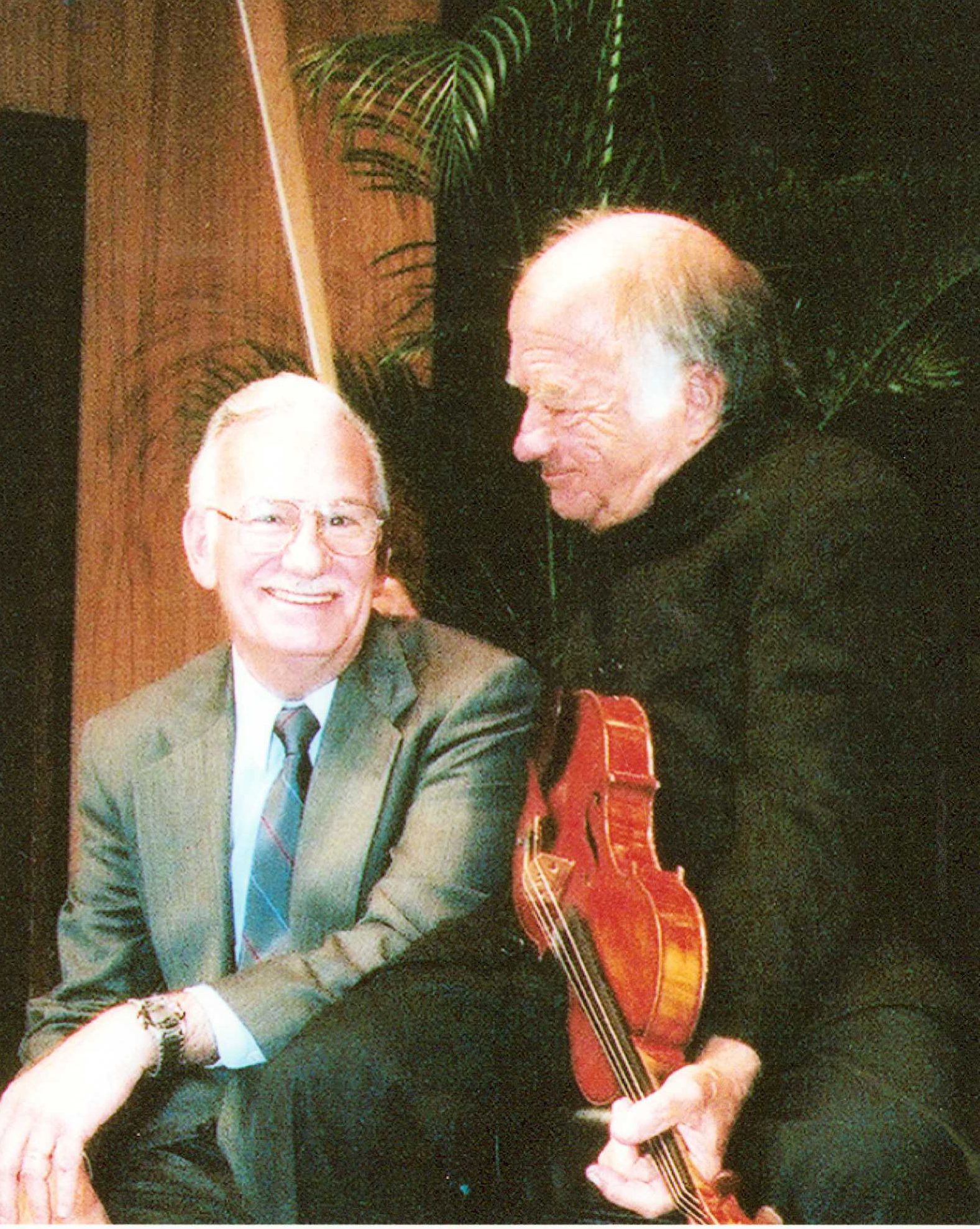

Luiz Bellini with Ruggerio Ricci, 2002

Born in Paris in 1924, Jacques Français was the descendant of a long and important lineage that could trace its pedagogical roots back to Nicolas Lupot. He worked for his family firm in Paris from the age of 12 and was sent to America in 1947 to spend a year working for Sacconi. Less than a year after returning home to Paris, he left again for New York and soon established his own shop on 57th Street near Carnegie Hall. In 1964, René Morel joined Français and the two eventually became partners.

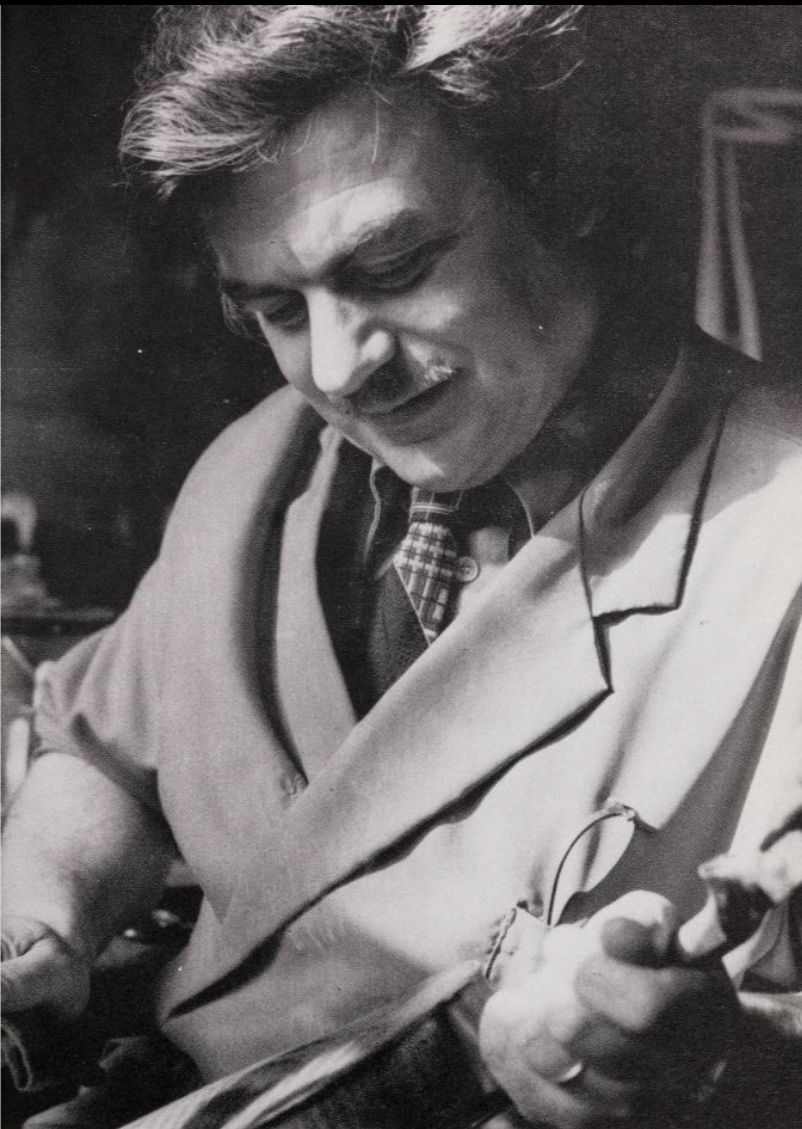

René Morel, chief restorer and Vice President of Jacques Français Rare Violins.

Born in 1932, Morel was twelve years old when he started working with Amédée Dieudonne in his hometown of Mirecourt. Later, he worked with Marius Didier and Bossard Bonnel in Rennes. As a young man, Morel served in the French Air Force before immigrating to Chicago, where he worked at the Kagan & Gaines music shop. In 1955, he moved to New York to work with Sacconi at Wurlitzers. Nine years later, he went to work with Jacques Français on 54th Street. From 2008 he worked in collaboration with Tarisio until he passed away in 2011.

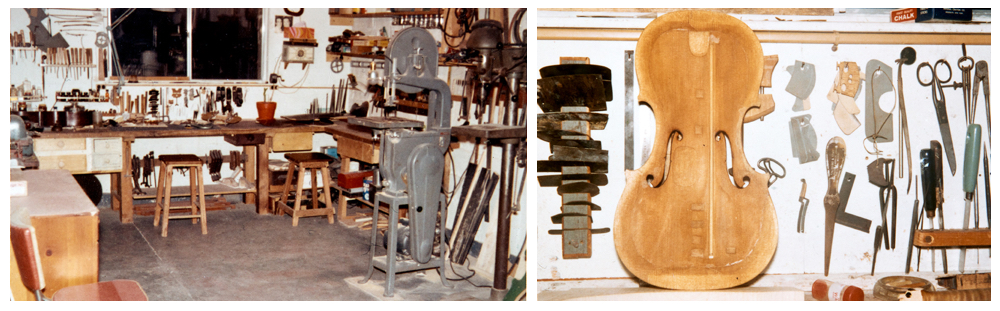

René Morel’s workshop at his home in New Jersey.

Morel was considered by many to be the best restorer and adjuster in America in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Isaac Stern, Yo-Yo Ma, Itzhak Perlman and hundreds of others from all across the world all came to him for repairs and adjustments. Like Sacconi, Morel also trained the next generation of makers and restorers: Horacio Pineiro, Emmanuel Gradoux-Matt, Gael Français, Otto Karl Schenk, Richard Oppelt, James McKean, Sam Zygmuntowicz, Guy Rabut, Hermann Fassler and Štefan Valčuha.

And now, halfway through the third decade of the 21st century, there are more great makers who call this city home than ever before. We salute the New York violin and bow makers and restorers of the next generation. The tradition continues…

Morel working alongside Gael Français, Jacques’s nephew.

- Philip Kass, The American Violin (New York: American Federation of Violin and Bow Makers, 2016), p. 51.

- See, Frederick R. Selch, Early American Violins and Their Makers, Journal of the Violin Society of America, vol. VI, no. 1 (1980) pg. 33-42).

- Kass, p. 51.

- https://ota.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/repository/xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.12024/3151/3151.html

- IBID., p. 53.

- Thomas James Wenberg, The Violin Makers of the United States (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1986), p. 119).

- Georg Gemünder, The Violin: Georg Gemünder’s Progress in Violin Making (Astoria: 1881), p. 11).

- Official catalog of the New York Exhibition of the Industry of all Nations, 1853, p. 94, https://catalog.library.cornell.edu/catalog/5404908

- Gemünder, p. 12.

- “OTTO GEMUNDER DEAD.; Was Son of the Famous violin Maker, and Himself Skilled in the Craft,” New York Times, June 13, 1901, https://www.nytimes.com/1901/06/13/archives/otto-gemunder-dead-was-son-of-the-famous-violin-maker-and-himself.html.

- Wenberg, p. 137.