New York has always attracted the best and the brightest. But it also attracts its fair share of troublemakers so it comes as no surprise to learn that New York’s first documented violin maker was a convicted felon who died in a botched robbery attempt. Geoffrey Stafford came to America from England around 1690 and settled in Massachusetts. He was conscripted and sent to fight the indigenous populations in the Albany territories in northern New York where he met and befriended the Royal Governor of New York, Benjamin Fletcher.[1] That a governor and a convicted felon could become friends was as extraordinary as it sounds, but perhaps the relationship flourished owing to Fletcher’s own notoriously unscrupulous record. During his administration, New York had become somewhat of a safe haven for outlaws and criminals. Stafford and Fletcher got along so well that Fletcher brought him to New York City. There are records of Stafford making violins in New York in the early 1700s, although no known examples survive today.[2]

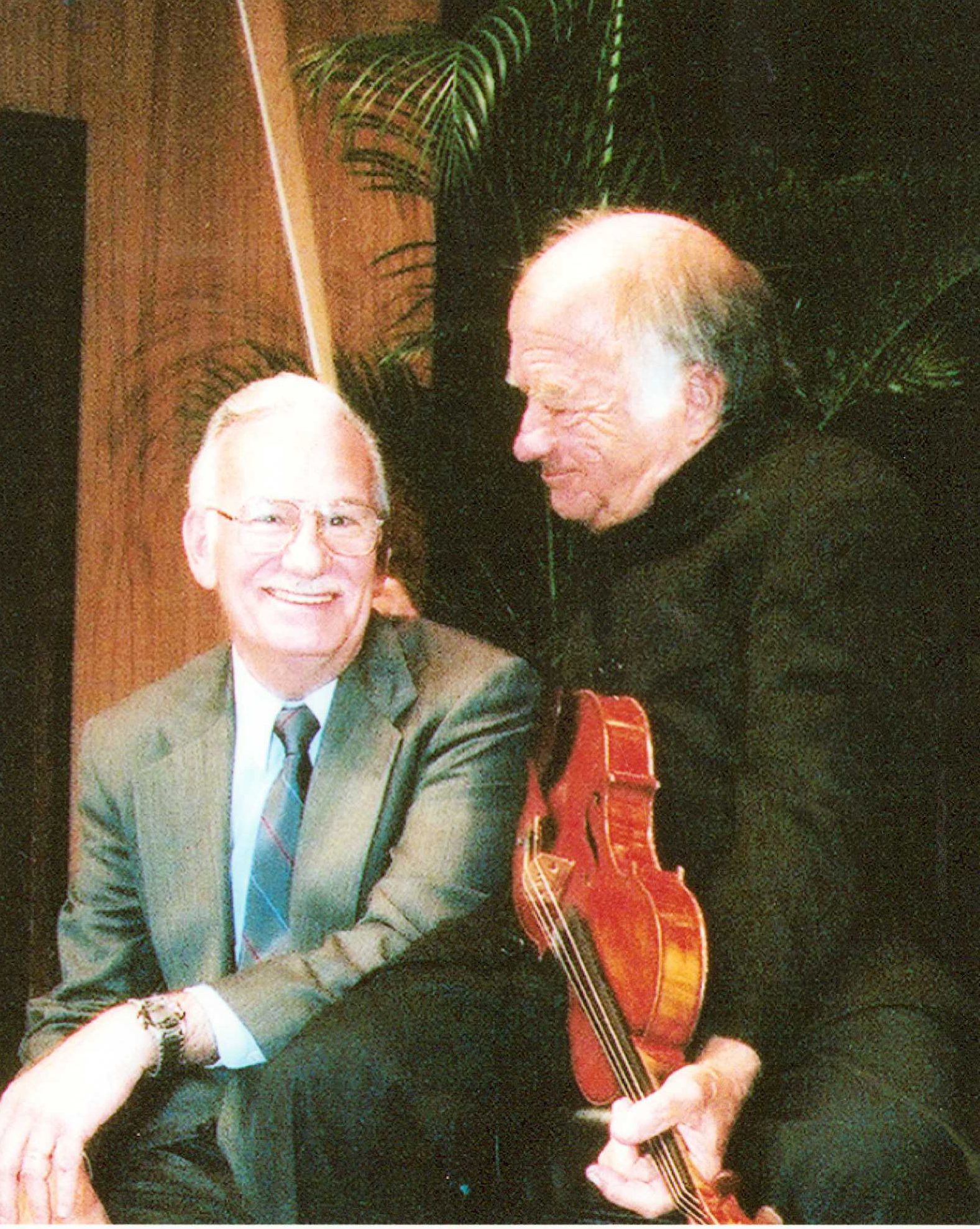

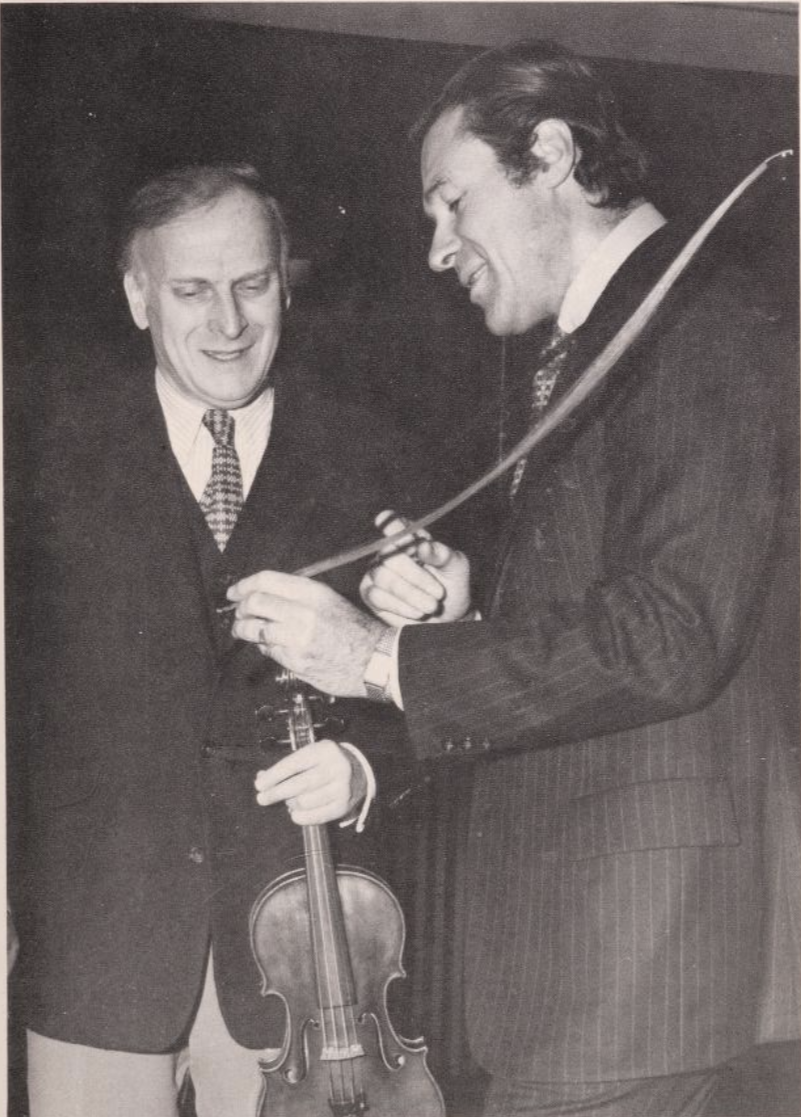

Jacques Français showing Yehudi Menuhin a bow made by Tourte and owned by Thomas Jefferson.

Stafford’s time in New York was cut short after he murdered Fletcher’s valet. Exiled from the city, Stafford took to the road again. Some time later he was involved in a failed robbery attempt and was hanged by his would-be victim.[3]

By the mid-18th century, Robert Horne had settled in New York. A viola by Horne dating from 1757 is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and is considered to be the oldest surviving violin family instrument made in the United States. Horne was proficient on a wide range of instruments and services. An advertisement appearing in the New-York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury newspapers in 1772 offered: “Violins, tennors, violon-cellos, guittars, kitts, aeolus harps, spinnets, and spinnets jacks, violin bows, tail-pieces, pins, bridges; bows hair’d, and the best Roman Strings.”[4]

A viola by Robert Horne, New York, 1757, Metropolitan Museum of Art

By the end of the 18th century, several other luthiers had established themselves in the city. In 1789 Thomas Dodds, a harpsichord maker with no relation to the English instrument and bow making family, sold a harpsichord to President George Washington. In the early 19th century, a violin maker from Boston, Paul Lamson, was advertising his services in New York. In 1818, Nicolas Antoine Lété of Mirecourt established a musical instrument import business. By 1820, Lété had returned to France where he hired a young violin maker named Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume.

Claude Augustin Miremont spent a decade in New York from 1852 to 1861.

Over the course of the 19th century, many makers from France and Germany immigrated to New York City: Charles Mercier settled there in 1840; Mattias Sprenger immigrated in 1846 and opened his shop in 1849; George Gemünder came to New York in 1847; John Strodl maintained a shop in New York City between 1852 and 1880; and Claude Augustin Miremont worked in New York between 1852 and 1861. Gemünder, Miremont and Strodl all entered instruments in the New York Exposition of 1853-54. Miremont and Gemünder were awarded medals but it was Gemünder who soon became New York’s preeminent violin maker.[5]

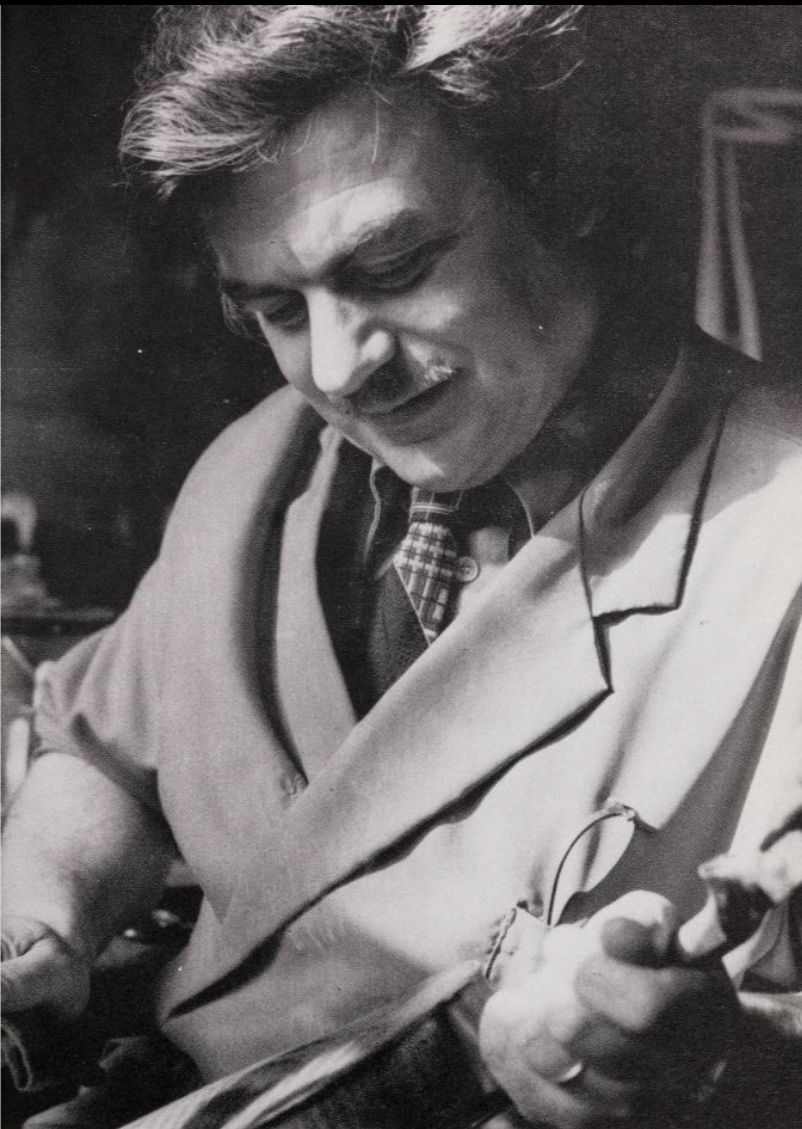

The Gemünder family

Born in 1816 in Ingelfingen, Germany, George Gemünder first trained under his father and later went to work for Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume in Paris. George’s brothers, August Martin Ludwig and Albert, were also involved in the instrument trade and by the mid 1840s they were running an organ shop in Springfield, Massachusetts. August and Albert convinced their brother to join them in America and he arrived in 1847.[6] The Gemünder brothers formed a traveling quartet composed of clarinet, flute, bass guitar and violin.[7] When their musical career failed to take off, George moved to New York City to open a violin shop in 1850.

At a time when his contemporaries regularly imported tonewood from Europe, Gemünder often utilized American sugar maple and once even made a violin out of spruce reclaimed from the joists of a demolished Manhattan church. The catalog to the 1853-54 New York Exposition noted that the instruments Gemünder submitted were made with “American materials, except for the strings.”[8]

After Gemünder was awarded the first prize in London’s Great Exhibition, Ole Bull, the Norwegian soloist noted, “Now you shall become in America what Vuillaume is in Europe.

A postcard from George Gemünder to his “friend F. (Francis) Wayland-Smith”, sent from his 949 Broadway Address on December 16, 1892. Smith was a violinist living in Oneida, New York, and the principal violinist of the community orchestra for the sect of Christian Perfectionists that would found the tableware manufacturing giant Oneida Limited.

With his training in the Vuillaume workshop and having won prestigious awards from the London and New York world’s fairs, George Gemünder quickly became one of the most important makers, not only in New York, but in the entire United States. After Gemünder was awarded the first prize in London’s Great Exhibition, Ole Bull, the Norwegian soloist noted, “Now you shall become in America what Vuillaume is in Europe.”[9]

In 1859, Gemünder’s brothers joined him in New York. Albert continued to work as an organ builder. August’s output of violin family instruments grew to rival Gemünder’s and notably, he was significantly better at business. For the next fifteen years, the Gemünder family worked side by side in Manhattan. George had three sons, George Jr., Hermann Ludwig and Otto. August also had three sons, August Martin, Rudolf Frederick and Oscar.

In 1874, George Gemünder moved his workshop to Astoria, Queens. At that time, Astoria was only accessible from Manhattan by ferry and this move caused George’s business to suffer. August’s business in Manhattan, on the other hand, continued to thrive. Seeing his brother’s booming business, George re-opened a shop in Manhattan in 1886 and called it George Gemünder & Sons. Following suit, August changed his firm’s name to August Gemünder & Sons four years later.

In 1889, George Sr. suffered a stroke and his sons took over operations of the workshop. George passed away a decade later in 1899. Two years later Otto died at the age of 30. His obituary, which appeared on June 13 in The New York Times noted that, “up until his death in Astoria two years ago, Otto Gemünder was his [father’s] constant companion.”[10] Hermann died in 1912, followed by George Jr. who died bankrupt in 1915. The family firm George Gemünder & Sons closed that same year.

August Gemünder died in 1895 and his sons continued the workshop. August Gemünder & Sons continued in business until 1946.