Any responsible discussion of violin labels begins with a caveat: most labels you will see are false. Refuse to believe they are original until you absolutely cannot not accept them as authentic. But then, when you do find an original label, study it as long and as carefully as possible. Labels, when they are irrefutably original, are the building blocks of expertise; without them, we would know very little about the classical makers.

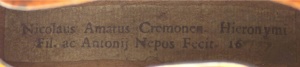

From studying labels we can learn where and when a maker worked (‘fecit Venetijs anno…’), his origins (‘Cremonensis’), his relationship to other makers (‘Hieronymi Fil. ac Antonij Nepos’), with whom he studied (‘alumnus Nicolai Amati’), the addresses at which he worked (‘in Contrada Larga’), and his age (‘aetatis suae…’). We can also make inferences about the maker’s circumstances. A maker who copies the style and format of another maker’s label might be a pupil or a follower. The number of spelling mistakes or grammatical inconsistencies in a label text might indicate the maker’s education and literacy, or his attention to detail. A maker who continued to use a flawed or outdated label could be assumed to be frugal. A maker who embellished his label with religious or Masonic symbols might be giving us a clue about his private life and affiliations.

There are infinite variations in printed labels. Some are short and some are long. In the 19th century it became fashionable to list the prizes and awards the maker had won. In the 20th century some makers printed a photograph of themselves on their label. In the 21st century, some tech-friendly makers have used QR codes and near-field chips. But the one thing that nearly all labels tell us is the date when the instrument was made.

Last week’s discussion of Balestrieri’s label with its three printed digits, ‘176_’, started me thinking about all the variations in which makers treat the date format on their printed labels. Since the late 16th century, printed labels for violins have been made in batches. We know this from observing the same version of a label used repeatedly over the span of many years. Printed labels were made most often with moveable type, and most likely they were printed by local printers at the request of the maker. Regardless of the technique, the maker – or the printer – had a choice in how to represent the year: he could print no digits of the year, some of the digits, or all of the digits. Since the mid-17th century the majority of makers have had the first two digits, the millennium and the century, printed on the label, while leaving blank the decade and year; those were to be hand-written upon completion of the instrument. This allowed the maker to order a batch of labels which would theoretically last until the next century. But this wasn’t always the case. This week, inspired by the efforts of Balestrieri, I have put together a thoroughly non-scientific and non-comprehensive survey of makers who printed the dates on their labels in unusual ways.

Printed labels with and without space for the date

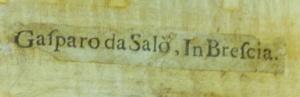

Few original labels survive from the 16th century so it’s unlikely we will ever have an accurate accounting of the labels used by the earliest makers. In Brescia, the surviving labels of Zanetto Micheli and his son Peregrino (‘Zanetto in Bressa’) are undated. Gasparo Bertolotti ‘da Salò’ and Giovanni Paolo Maggini used printed labels but did not include a date, to the best of our knowledge.

The labels are basic and perfunctory (‘Gasparo from Salò, In Brescia.’, ‘Gio. Paolo Maggini in Brescia.’), they give no extraneous information, and leave no room in the typography to insert a year. Giovita Rodiani (‘Giovita Rodiani in Brescia.’) and Giovanni Maria da Brescia who worked in Venice also used an undated printed label (‘Juan Maria da Bressa: fece in Venecia’). This is the reason why the early Brescian instruments are never cataloged with a precise date.

Maggini followed the model of ‘da Salò’, basic and perfunctory. In this example, the ‘1650’ was likely added later, and not by the maker.

The original printed labels that survive today are only a small fraction of those that were created

It’s important to acknowledge that the evidence is extremely limited regarding the 16th and early 17th century makers, and it’s impossible to make conclusions or even generalizations with so many unknowns. The original printed labels that survive today are only a small fraction of those that were created, so we must consider that there are many labels and variations of labels that have been lost entirely to history. Furthermore, the existence of printed labels in plucked instruments and early, non-violin family instruments is outside of the scope of this quick survey.

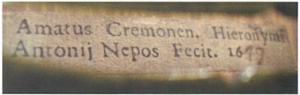

Of the surviving instruments of Andrea Amati there is considerable doubt that any labels are original. Those that might be, or that might have been copied in the same format and syntax as the original, usually give the date in Roman numerals: ‘ANDREA AMADI IN CREMONA MDLXIV.’

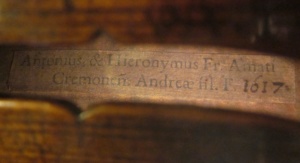

Andrea Amati’s sons, Antonio and Girolamo, used a printed label and wrote the four digit year by hand. After stating their names in Latin (Antonius & Hieronymus), their relationship (brothers), their nationality (Cremonese), and their lineage (sons of Andrea), there is a trailing ‘F.’ for ‘fecit’. The date was customarily handwritten in the space after the ‘F.’.

The label from the 1617 ‘Zukerman, Kashkashian’ Brothers Amati viola.

The layout of the text on this label is interesting in that the printed portions of the first and second lines are centered with seemingly no allowance made for the fact that the addition of the date would skew this alignment. It’s important to consider that the final ‘F.’ could just as well stand on its own and end the sentence; it didn’t necessarily have to have been followed by a date. Perhaps the inclusion of a date was not foreseen when the labels were commissioned. Or perhaps the centering of the text was decided by the printer. The centering of the second line may or may not have significance, but it could support the theory that this label was originally intended to be used undated.

Antonio and Girolamo dissolved their partnership in 1588, but Girolamo continued to use the Brothers’ label for another four decades. There are also a few surviving labels which list only one brother’s name. The National Music Museum in Vermillion has in their collection a small violin with an original label of Girolamo. The format, typeface, and syntax are the same as the Brothers’ label (without the mention of Antonio), and the printed ‘F.’ is followed by a manuscript date. But unlike the Brothers’ label, the layout of the printed text on Girolamo’s label clearly leaves a dedicated space in which the date is to be handwritten.

A label in a violin by Girolamo Amati. The typography makes space for the handwritten date of 1604.

Girolamo’s son Nicolo inherited the family business in 1630, but instruments with Nicolo’s original labels are virtually unknown until the 1650s. In fact the earliest surviving original label may well be the one in the 1649 ‘Alard’.

The label in the 1649 ‘Alard’ by Nicolo Amati in the Ashmolean Museum (Photo: John Milnes. Courtesy of Ashmolean Museum.).

We may never know for sure, given the rarity of labels from this period, but I have a theory that Nicolo Amati was the first violin maker to print a two digit year onto his label. I haven’t encountered another original label from before 1650 with a partially printed date. For Nicolo it was probably a rational decision: he knew he wouldn’t live beyond the turn of the next century and this was the layout that would last the longest. There are several versions of Nicolo’s label but they all, to my knowledge, make use of a printed ‘16’ and a space to hand-write the decade and year.

Whether or not Nicolo Amati was the first to use a two digit printed label, this soon became standard practice. Ever since, most makers using printed labels, regardless of their country or language, created ones in which two digits of the year were printed and two were hand-written. There are exceptions, of course, and the following is a short, and not-at-all definitive catalog of notable variations.

Makers who used labels with one, three, and four printed digits

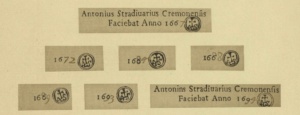

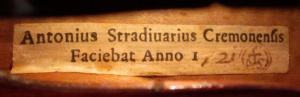

The label that Antonio Stradivari used from the mid 1660s to the late 1690s had three printed digits, ‘166_’. This was perhaps a rookie mistake from an overly ambitious young craftsman who thought he would order a new stack of labels every ten years. Stradivari was very productive in the 1670’s, 80’s, and 90’s, and yet it appears that this was the only label version he used during that period.[1] After 1670, the problem of the second ‘6’ presented itself and we can observe Stradivari’s workarounds in the surviving labels of the next three decades. In the 1670s there are labels where it appears that the ‘7’ has been scraped off. In the 1680s the top of the printed ‘6’ was looped over to make an ‘8’. In the 1690’s a tail was added to the lower circle of the ‘8’ and the upper circle was removed. The Hills observed this and illustrated it in their 1902 monograph on the maker, a page of which is reproduced below.

An illustration from W. E. Hill & Sons’ monograph on Antonio Stradivari, published in 1902.

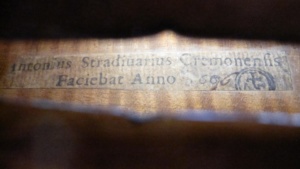

A label from 1696, the third decade of Stradivari’s work-around.

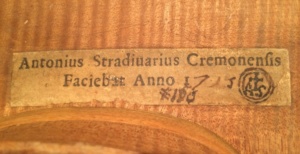

Sometime towards the end of the 1690’s, Stradivari had a new batch of labels printed which would last him for the next three decades, until nearly the end of his career. In this new format he printed only the millennial ‘1’ of the date, obligating himself to hand-write the final three digits.

The label from the 1725 ‘Portuguese’ Stradivari.

The label from the 1721 ‘Lady Blunt’ Stradivari.

I’d like to study Andrea Guarneri’s labels, particularly the earliest examples. I would expect that they would follow the format of his teacher, Nicolo Amati, but I haven’t seen enough labels that I trust are original to report this.

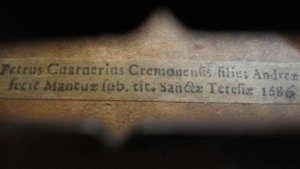

Pietro Guarneri, son of Andrea, arrived in Mantua in 1680, and the first original label that we know from him has three printed digits, ‘168_’. His conversions post-1690 were less strategic than Stradivari’s solutions and often the ‘8’s are forcefully effaced into a ‘9’.

The label from the ‘Duke of Mantua, Viret’ of 1686.

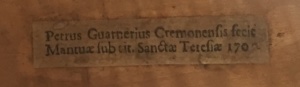

Interestingly, when Pietro had a new batch of labels made up at the turn of the century, he committed the same error and printed ‘170_’, forcing a new set of variations ten years later.

Pietro Guarneri’s label after 1700.

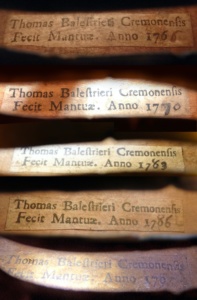

Later in Mantua, Tomaso Balestieri had a three digit label printed, ‘176_’, which he necessarily adapted over three decades of use.

Balestrieri labels from the 1760s-90s.

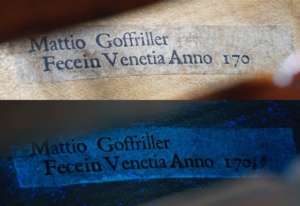

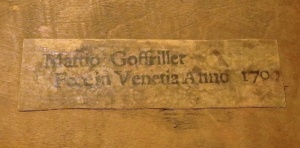

In Venice, Matteo Goffriller’s instruments are frequently unlabeled, but at least one version of his label survives with three printed digits.

A Goffriller cello with three printed digits, written in Italian, not Latin.

In another example, examination under UV light reveals that a manuscript ‘10’ was added after the ‘170’ to assign a date of either 1701 or 1710.

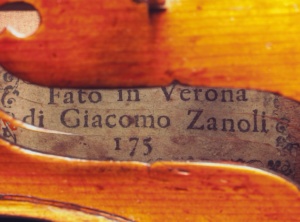

In Verona, Giacomo Zanoli used a beautiful three digit label with Italian text, ‘175_’.

A composite image of a label from a violin in the collection of Yale University.

Antonio Gragnani used at least two versions of a three digit label, ‘177_’ and ‘178_’. In the following illustration the second and fifth labels show his modifications at the turn of each decade.

I have also seen labels with three printed digits of Giovanni Tononi (170_), Gaspar Lorenzini (175_), the Fratelli Gagliano (181_), Floriano Guidantus (169_), and Louis Guersan (174_). I’m sure that many others will come to light over time.

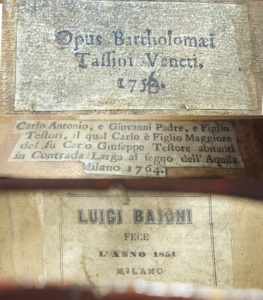

The last category of labels are those with four printed digits. I would like to see more research on this subject, but for the moment, I can refer only to labels by Bartolomeo Tassini (1752), Luigi Bajoni (1854) and an unusually verbose and grammatically complicated label of Carlo Antonio Testore and his son Giovanni dated 1764.

Highly ambitious or spendthrift makers used a label with four printed digits.

A label for just one year

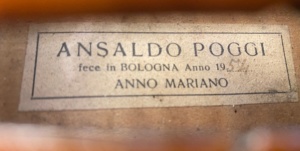

And finally, a special label from a 20th century maker. If there ever were the right moment for a maker to create a label with the full four digits of the year spelled out on the label, this was it. A Marian year (‘Anno Mariano’) is a year designated by the Catholic Church in which the Madonna is to be particularly celebrated, or revered in a specific diocese. There have only been two international Marian years, the first declared by Pope Pius XII in 1954[2] and the second by Pope John Paul II in 1987. In 1954, Ansaldo Poggi, evidently an observant Catholic, created a special batch of labels to commemorate the ‘Anno Mariano’ and inserted them in the instruments he produced that year. Notwithstanding the fact that he obviously printed a bespoke label for this purpose, he still printed only two digits of the year, perhaps hoping to keep the leftovers for the next Anno Mariano!

From a viola recently consigned to Tarisio Private Sales, a label printed for a specific year but still with only two printed digits.

Jason Price is Tarisio’s Founder, Expert, and Director.

Notes

[1] Excluding the ‘Alumnus Nicolaij’ label. And although this version appears to be the only format in use, there exist several typographical variations including the apparent printer’s error of the upside down ‘u’ in ‘Antonins’.

[2] The Anno Mariano went from December 8, 1953 to December 8, 1954, so technically Poggi could have printed a three-digit label.