The Voller name has acquired a mixed reputation over the years. It is not a name you want to hear if you believe that your instrument is a fine old Italian. On the other hand, if you believe it to be an anonymous old fake, ‘Voller’ will be a welcome suggestion. It seems not long ago that the Vollers were known only to experts and insiders; not to be advertised because of their association with deliberate deceptions, fakes or other dirty dealings. But the reputation of the Voller brothers has increased with recognition of their talent, and another danger, a slightly ironic one, has emerged: the temptation to upgrade lesser instruments with the Voller name. Their very success at remaining hidden under assumed names for so long has brought about an appreciation of their skill and value as instrument makers.

The Voller Brothers, William, Alfred and Charles, emerged in late-Victorian England as the sort of faceless craftsmen that flourished in back streets and small workshops throughout the city of London and its growing suburbs. They belonged to the lower middle class: people with a basic education and access to a musical training, and it would seem good aspirational prospects. Their father, Henry Voller, was a cabman and the family lived in a small house in Marylebone, albeit at the poorer end. William, the eldest (born in 1854), played the viola, painted watercolours and even made a bronze sculpture of Alfredo Piatti with his 1720 Stradivari. Alfred (born in 1856) played the cello, while the youngest, Charles (born in 1865), studied the violin under Ludwig Straus. William initially established himself as a music teacher and by 1887 was successful enough to move with his brothers and sister a short distance to a new and larger house in Brewster Gardens. In the interim, he had been drawn to the shop of Frederick Chanot in Wardour Street, and a new career as a violin maker.

Left: the Voller’ copy of the 1710 ‘Vieuxtemps’ Stradivari, made for Hart & Son in 1897; right: the original ‘Vieuxtemps’ Stradivari

More photosFrom Chanot, William moved into the orbit of George Hart, at that time the most important violin dealer in London. His Wardour Street shop had been established by his father, John, in 1827, and his own pioneering book The Violin: Its Famous Makers and Their Imitators, published in 1875, had helped him to become a respected expert and connoisseur. George was at that time bringing his own son, George II, into the business, and he took over the shop after the elder George’s death in 1891. It was soon after this that the Vollers began serious work for the younger Hart.

At the same time the Hills were also establishing their business in New Bond Street, having left Wardour Street in 1881, and were shortly to publish the first of their seminal works on the violin. The monograph on the ‘Messiah’ Stradivari of 1716 was their debut, published in 1891, and marked their success in having obtained the violin in the previous year. An uneasy relationship developed between the two rival houses.

[The Hills] were clear that all three brothers were already working together to make ‘sham instruments’

The Hills were aware of the Vollers as early as 1890. In 1891 they observed four imitation Gragnanis, which they attributed to the Vollers, handled by a part-time dealer, Dr George Duncan (1852–1935). They were clear that all three brothers were already working together to make ‘sham instruments’ and noted in particular Cappa, Panormo and Testore copies passing through the salerooms. Duncan was the Vollers’ patron. He retired from a successful medical practice in 1891 to indulge in his interest in violin dealing, and the Hills believed he was their main client until at least 1895.

Some unfortunate court cases came to attention during this time. George Chanot, father of the Vollers’ associate Frederick, appeared in court over a misrepresented Bergonzi in 1882, and in 1890 a famous dispute between the Glasgow dealer David Laurie and his client Mr Johnstone over the authenticity of a Stradivari also was heard in court. Duncan himself was summonsed in 1898 in a dispute about the real identity of Stradivari, Bergonzi and Guadagnini violins.

This was the context of the Vollers’ early career. But 1894 marks what seems to be their debut for George Hart, and some legitimacy as genuinely skilled violin makers in their own account. The violin featured above (Lot 193 in the June London auction) bears Hart’s own label, dated 1894 and marked both no.37 and no.1; an additional label placed beneath states it to be ‘an exact copy of the late Mr Hart’s famous Joseph Guarnerius’. It is very clearly the work of the Brothers. This would seem to be saying that it is no.37 of Hart’s production, but no.1 of the Vollers’ commissioned work for him, and it is indeed a remarkably close copy of the ‘Hart’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ of 1741, which bears the name of its first recorded owner, the first George Hart, who had died three years previously. In 1904 it became the favorite violin of Fritz Kreisler, about which he later said: ‘I shall never hear a voice more beautiful than my “Hart” Guarnerius.’ No wonder the younger George Hart seized the chance to have a copy made – his father had apparently resisted all attempts to buy it from him.

It is what might be called an honest imitation, accurately labeled and unlikely to pass for the real thing

The Voller copy naturally uses well-matched wood, with the close flames of the back arranged to rise from the center joint. The work is a little exaggerated, the edges broad and the cutting of the head not particularly well defined. But the significant elements are caught accurately. The f-holes are fluted in the oddly superficial way that ‘del Gesù’ had in this period, and the corners are dug deeply with a small gouge in precisely the manner of the original. The varnish is perhaps inevitably a little flat and lacks the sparkle and depth of the original, and the Vollers made no attempt to copy the interior structure accurately. It is what might be called an honest imitation, accurately labeled and unlikely to pass for the real thing.

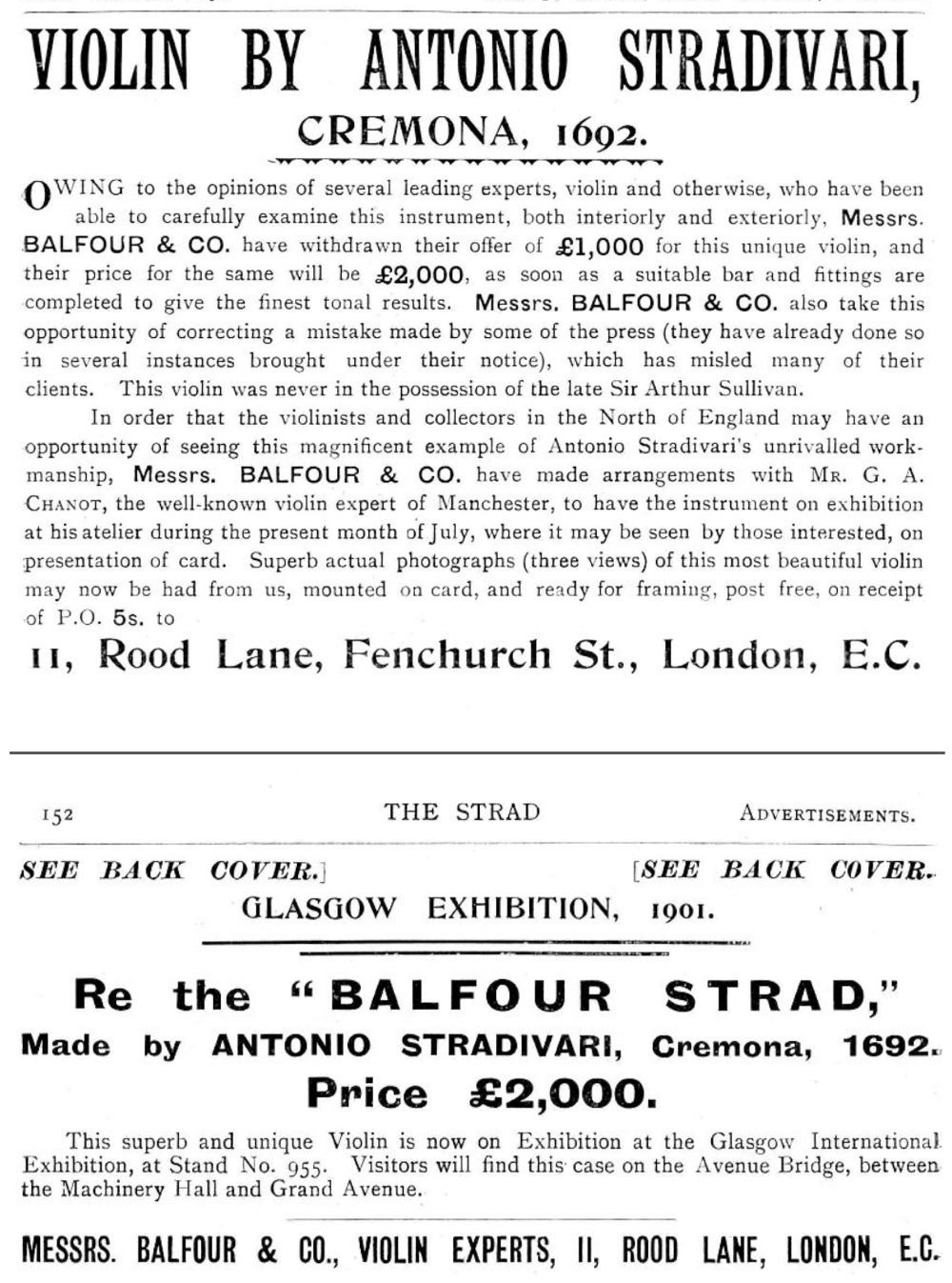

This violin led to some wonderful copies made for Hart of the 1743 ‘Leduc’ and 1735 ‘D’Egville’ Guarneris and many precise Stradivari copies, some made for private clients outside the Hart shop, including remarkable imitations of the 1701 ‘Nachez’ and the 1691 ‘Red Cross Knight’. But their success brought them close to their undoing. They appeared to watch another damaging court case from the sidelines, when a generic Stradivari copy they had made had been offered in public advertisements as genuine. The notorious ‘Balfour Strad’ appeared for sale in 1901, offered at a Puttick & Simpson auction by Balfour & Co., whose director Vincent Cooper was trying to launch himself as a violin dealer. How he obtained the violin is not known, but it must have been pretty fresh from the Vollers’ workshop when it arrived at Putticks, rather than ‘from the continent a few days ago’ as the auction catalog declared.

Adverts from The Strad, July 1901, promoting the sale of the ‘Balfour Strad’

The violin world took sides. On one side was Georges Adolphe Chanot in Manchester, Horace Petherick, the self-styled expert and journalist, and several Parisian opinions gained in support. Opposed were the Hills and, unsurprisingly, George Hart. William Voller himself took the step of writing to Balfour & Co., warning them not to sell the violin as a Stradivari, but Cooper ploughed on. They sold it to an amateur, who quickly brought them to court in 1904, where William Voller provided a sworn affidavit that he had made the violin. But the Balfour firm went bankrupt and their customer died soon afterwards, and the violin subsequently found its way to the continent, passing from one dealer to another until the late 1950s. The instrument would fool few people today. It is a generic copy of a pre-1700 Stradivari, lacking any of the distinctive marks of Stradivari’s own technique; on the other hand, it is a refined and beautiful instrument in its own right and a very sophisticated piece of workmanship.

William Voller himself took the step of writing to Balfour & co., warning them not to sell it as a Stradivari, but Cooper ploughed on

The Vollers continued working very successfully. Hart pioneered the violin trade in the US, probably being the first dealer to take Stradivaris to North America, and found dealers there hungry for whatever he could send. To those who couldn’t get their hands on the real thing, Voller imitations offered an attractive alternative, finding their way to German dealers with equal ease. Their copies were sometimes ‘cocktails’ made from parts of genuine old instruments, fitted together sometimes with new pieces made by the brothers. Many Voller instruments seem to have an old head, salvaged from somewhere to add to the air of authenticity. Some, it has to be said, are somewhat crude and were clearly put together in haste. But in others their great skill and experience shines through.

This late Voller Brothers viola is an excellent Tononi copy. Photos: courtesy Ingles & Hayday

It is next to impossible to establish dates for most Voller instruments, given the very rare appearance of their own name on labels. However, dendrochronology provides a date sometime after 1922 for what must be one of their very last productions, a beautifully observed imitation of a Tononi viola. This was certainly made after Alfred had died in 1918 and is most likely the work of the Charles, the youngest. William, the eldest brother, was already 68 when the tree from which the front was cut was still in the ground. It is a truly beautiful instrument, with the subtlest of touches in finish, varnish and construction and absolutely capable of passing for the real thing. Yet one little twist gives it that proper Voller character: inside are two labels. One is in the usual place, and carries the plausible name Joannes Tononi, but with the implausible date of 1737. But another label was inadvertently left behind when the 1737 label was placed by a later hand, it may be assumed. This second label, caught on a lower rib, has the name Pietro Tononi, 1703, and is probably the one Charles Voller originally inserted. Pietro Tononi is a rare, almost unknown maker, very much more difficult to verify than his brother. Crafty!

A fine and important violin by the Voller Brothers, 1894, was sold by Tarisio in our London June auction.

John Dilworth is a maker, writer and expert. He has written extensively about fine instruments and their makers, and is a co-author of ‘The British Violin’, ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ and ‘The Voller Brothers’ among other books.