Antonio Antoncich Craglietto was born into a modest family in the small Croatian fishing village Veli Lošinj on November 22, 1868, the day of Saint Cecilia, patron saint of music and musicians. This may have been fate, as music and musical instruments were to be the great passions of his life. From Croatia to Chile, where he made his fortune, Antoncich was never far from music. By the time of his death in 1955, he had amassed one of the greatest collections ever of stringed instruments in South America and had contributed significantly to the development of European musical culture in Chile.

Antoncich in the Music Hall of his home in Valparaíso (Courtesy of the Antoncich family).

Antoncich was born into a musical family. His uncle, Vittorio Craglietto, was a music teacher in Veli Lošinj and probably introduced the young Antonio to music and gave him lessons.[1] Antoncich’s younger sister Costanza was a singer who trained in Trieste and Milan and hoped to sing at La Scala but died of consumption before she could realize her dream. His grand-niece, Luisa Scrivani, recalls that Antoncich was proud and determined, but life in Veli Lošinj was quiet, and there was little opportunity for such an ambitious man.[2]

Twice, Antoncich tried and failed to leave Croatia. He first emigrated to Trieste to work for the shipping company, Österreichischer Lloyd, but was dismissed for poor performance.[3] Then, around 1890, he and his younger brother Federico booked a third-class passage on a steamer bound for New York. While Federico made his way in America, less than a year later a disheartened Antonich returned to Veli Lošinj, complaining that America was cold and unwelcoming.[4]

Antoncich and his sister Costanza in Trieste (Courtesy of the Antoncich family).

On his third attempt, he left Dalmatia and arrived in Valparaíso, Chile in 1892. Integration there was easier for Antoncich than it had been in New York. At the end of the 19th century there was a large Croatian community in Valparaíso, and obtaining Chilean citizenship was straightforward for immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[5] Once a small village, by the 19th century Valparaíso had been transformed into an important port city. Known as the ‘Jewel of the Pacific’, Europeans flocked to the flourishing city and left their mark on its architecture and culture.[6] Like many port towns in the New World, it was a city of beginnings, where new and old cultural identities blended and were celebrated.

Antoncich’s collection, some of which remains unaccounted for to this day.

Resolved to succeed in South America, Antoncich found work with the Compania de Salitres y Ferrocarril, a mining company in Antofagasta in the north of the country. The company’s main product was saltpeter, or nitrates, which were used to manufacture fertilizer, gunpowder, and in food preservation. By the end of the 19th century, Chile was responsible for nearly 80% of the world’s nitrates giving it a monopoly over the production of this ‘white-gold’.[7] By 1910 its per capita GDP was the 15th highest in the world, almost equal to that of France and Germany and greater than that of its former colonial ruler, Spain.[8]

Antoncich rose quickly through the ranks of the company and in just four years was made a director. Through his work, he became friends with Pascual Baburizza (Pasko Baburica Šoletić), a fellow Croatian who had arrived in Chile the same year as Antoncich. The two developed a lifelong friendship in addition to their business interests and shared a nostalgia for the culture of their homeland. In 1910 Baburizza founded a mining company of his own, Baburizza & Co, which would later control 30% of Chile’s nitrate mines. Antoncich would come to own shares in the Baburizza company, which would prove key to his financial success.[9]

In 1914, as Europe mobilized for war, Chile found itself positioned between hostile nations intent to secure access to the supply of nitrates, a crucial ingredient used in explosives and munitions. Contending factions competed to control the pipeline, but after the Battle of the Falklands in late 1914, the English secured a near total monopoly.[10] In response, the Germans accelerated efforts to produce synthetic nitrate, which they successfully accomplished in 1915. The synthetic production of nitrate would eventually lead to the collapse of the Chilean saltpeter industry.

Nitrate mining in Iquique, northern Chile, in the late 19th century.

But in the 1910s and 20s it was boom time for nitrate mining in Chile. With this came financial success for Antoncich which he used to enrich his life with music. He began to play the violin again and took weekly lessons. His wife Amanda played both the piano and guitar and sang ‘romantic songs with a very sweet voice.’[11]

In Valparaíso in the early 20th century there were few public venues where European classical music could be heard. And so in 1918 Antoncich began hosting weekly music salons at his home. At first these were private concerts where a trio or quartet would play for a small audience of Antoncich’s friends. But quickly these amateur gatherings grew into proper recitals, featuring small ensembles and attracting an audience of fellow European immigrants who longed to listen to classical music. Soon Antonich’s home became the unofficial concert hall of Valparaíso and, with very few exceptions, put on live concerts every Monday evening between 1918 and 1937.

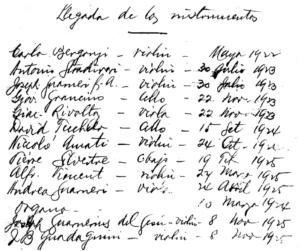

Encouraged by the triumph of his salon and flush with financial success, Antoncich began to invest in instruments. His first significant purchase was the ‘Naryshkin, Antoncich’ Bergonzi of 1743-47, which he acquired during a trip to Europe in 1922.[12] He bought the violin from W. E. Hills & Sons for £600 using the Baburizza company as his intermediary.[13]

The arrival of the Bergonzi violin elevated the social status of his salon, increased the popularity of his Monday soirees, and ‘consolidated the fame of the Antoncich Hall.’[14] Antoncich himself was so pleased with his purchase that he proposed to name his newborn daughter, the last of his eleven children, Bergonza, in honor of Carlo Bergonzi. Fortunately for his daughter, Antoncich’s wife and older children vetoed the name, perhaps because it sounded too much like vergüenza, or shame in Spanish. Instead they named her Cecilia, in homage to Saint Cecilia.[15]

Antonich’s home became the unofficial concert hall of Valparaíso and, with very few exceptions, put on live concerts every Monday evening between 1918 and 1937

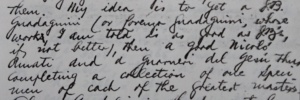

In a letter to John Wood on December 9, 1923 he wrote that it was his goal to own ‘one specimen of each of the greatest masters.’

The year after he bought the Bergonzi he acquired his second and third instruments, a Guarneri and a Stradivari. Upon their arrival in Valparaíso, they were immediately put to use, in a recital that evening featuring the pianist Maria Dvorak, the niece of the Czech composer.[16] Unfortunately, these two instruments would later prove problematic for Antoncich.

The first page of Antoncich’s notebook detailing his instrument collection (Courtesy of the Antoncich family).

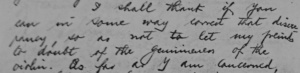

The violin ascribed to Giuseppe ‘filius Andreae’ Guarneri[17] had been sourced for Antoncich by the Baburizza company secretary in London, John S. Wood. A certificate from J. & A. Beare, Ltd. dated less than two years before Antoncich acquired the violin,[18] is made out in the name of Paul Brunet,[19] a violinist in the Queen’s Hall Orchestra and an amateur fiddle dealer. The problem arose when Antoncich noticed an inconsistency between the date on the label of the violin and the date written in the certificate. In itself, this is hardly a cause for alarm, but it seems to have developed into a crisis for Antoncich when his friends doubted the authenticity of his new trophy. Writing to Wood in August 1923, Antoncich asked if he could address this issue with Arthur Beare: ‘I shall thank [sic] if you can in some way correct that discrepancy, so as not to let my friends to doubt of the genuineness of the violin.’[20]

The Stradivari violin that Antoncich had also purchased that year was the 1699 ‘Camposelice’. The Hills had known this violin since 1887, having sold it three times, most recently to Alfred Cecil Bonvalot, a decorated captain in the English army and later a violist in the London and Pennington String Quartets. But this time it was Beare who sold the violin to Antoncich through Wood on the recommendation of an unnamed violinist. The £2,200 that Antoncich paid represented a hefty markup from the £950 that Bonvalot had paid four years earlier in 1919. Antoncich raised this with the Hills, who, no doubt, seized upon the incident to declare themselves the more honest brokers with whom he could transact without fear of being swindled.

From their correspondence we understand that the Hills had another reason to be bitter about this transaction. At the same time that Antoncich was considering the purchases of the ‘Camposelice’ and the ‘filius’, the Hills had also presented the 1690 ‘Auer’ Stradivari and the c. 1744 ‘Sainton’ Guarneri for sale. Unfortunately, owing to the time lag in sending letters between Valparaíso and London, their proposal arrived after Antoncich had already made his purchases.

Antoncich’s next purchase consisted of a cello by Sebastian Vuillaume and a viola by Lupot, both acquired locally in November of 1923.[21] And then at the end of the year he bought a 1712 Grancino cello, an 1829 Rivolta viola, a Grancino violin, a Tourte cello bow and a Voirin viola bow, again through his agent, John Wood.

It appears that Antoncich regretted the opportunity to acquire the ‘Sainton’. To Wood he wrote, ‘I am becoming an incorrigible collector […] if sales of nitrate improve, I intend to acquire a good Joseph del Gesú, possibly an instrument of historical importance, something like the Sainton Guarnerius Hill offered lately. You may tell them this, so that they may see it is in their interest to treat me well.’ From 1924 onwards he transacted primarily with the Hills.

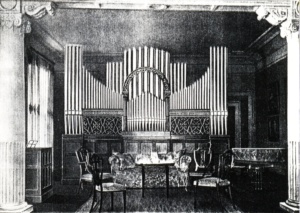

In 1924 he bought a Tecchler cello; a 1651 Nicolo Amati; and, in December, a double bass by Pierre Silvestre dated 1850. That same year he also imported a custom-made pipe organ from Gebrüder Link firm in Germany, which he had installed in his music room.

The organ from the Gebrüder Link firm in Giengen, Germany, installed in the Antoncich music room (Courtesy of the Antoncich family).

As the reputation of his music soirees grew, so too did the audience size. Wanting to accommodate larger crowds and ensembles, Antoncich bought his neighbor’s house in 1925. In doing so he was able to double the capacity of the salon and benefit from the use of a separate entrance.[22]

He also, in 1925, added three exceptional instruments to his collection: the ‘Primrose, Lord Harrington’ Guarneri viola, the 1735 ‘Antoncich, Ward’ Guarneri ‘del Gesú’ and a 1747 Guadagnini .

Like many collectors, part of Antoncich’s enjoyment was social. He liked to rub elbow with important musicians and made his home a destination for European musicians on tour including Claudio Arrau, Willy Burmester and many chamber ensembles. On June 27, 1926, Antoncich hosted the London String Quartet who were touring South America. Over lunch, he asked for their opinion on the Guarneri viola and Guadagnini violin which was ‘favorable’.[23]

Antoncich’s purchases slowed after 1926 as his fortunes were greatly diminished owing to the recession in the nitrates market. The last two instruments he acquired were the ‘Henry IV’ Amati viola and a violin by Giovanni Battista Rogeri which he acquired from Hills during a trip to Europe in 1935 in part exchange for the ‘Camposelice’ Stradivari.[24] In the years that followed, Antoncich slowly removed himself from this world. The weekly concerts in Antoncich’s home had ceased by 1937, and his wife Amanda died in 1941.

Antoncich with one of his sons in his home in Valparaíso (Courtesy of the Antoncich family).

The means by which Antoncich’s collection was dispersed are not fully understood. The Bergonzi remained in Chile until 1975; the Guarneri viola had arrived in New York by the early 1950s. The Amati viola was purchased by US Navy Commander Edgar K. Thompson[25] and was later sold by Sotheby’s in 1981. The Guadagnini appeared at auction in 1989.[26] The current whereabouts of the Tecchler, Rivolta, Grancinos, the Amati, and the alleged ‘filius’ remain unknown to me.

Antoncich, who had long suffered from Parkinson’s Disease, passed away in 1955.