Parisian wood

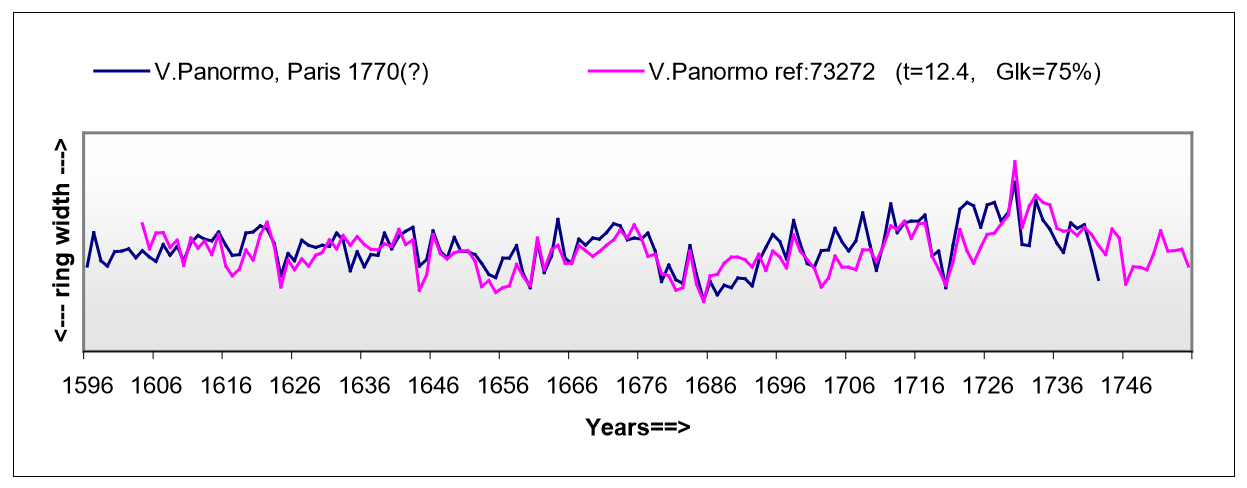

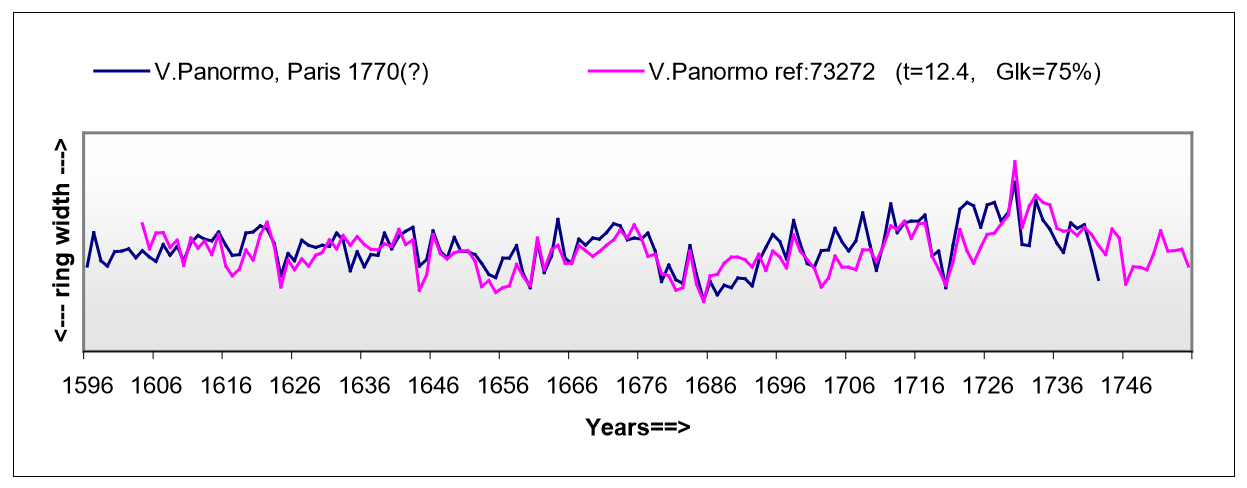

While the above is true for a fair proportion of Panormo’s instruments, some responded positively to cross-dating, in particular those from the periods in which Panormo was in Paris. In addition, when he used a single piece of wood to make a soundboard, the resulting larger number of rings provide extended tree-ring information over a much longer period of time. Tests on these instruments were generally more successful in obtaining dates and some of them were found to correlate extremely well together. The graphical plotted data from two separate pairs of instruments displayed strong visual similarities between their ring patterns. The results of the statistical cross-dating tests also strongly pointed to a same-tree origin for the tops, as the statistical requirements for the consideration of such an eventuality were exceeded in both cases. While the wood for one of these pairs of violins, both made in Paris, was easy to date (see figure 1), tests on the other two, which were probably made in Dublin, remained inconclusive. The successfully dated pair found very strong correlations with wood used typically in France during most of the 18th century.

Figure 1: The two ring-width patterns of the bellies of separate violins by Vincenzo Panormo, both reputed to have been made in Paris

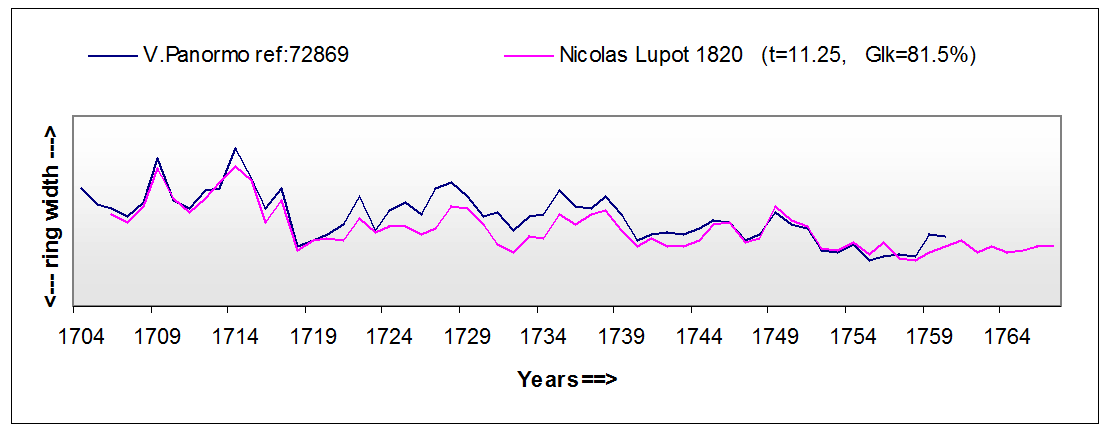

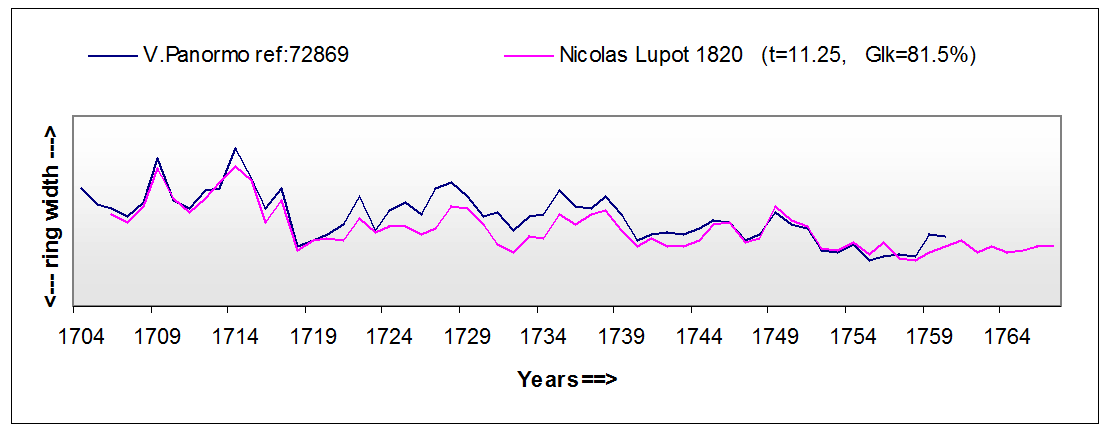

A further interesting and potential same-tree association was also identified between a late Panormo and a Parisian violin certified by Etienne Vatelot as a Nicolas Lupot from 1820. Figure 2 demonstrates the excellent correspondence between the two ring patterns:

Figure 2: Comparison of the plotted ring patterns from the bellies of a Vincenzo Panormo and a Nicolas Lupot violin

From these and other successfully dated examples, it would appear that the wood used by Panormo while in Paris responded similarly to many soundboards found on instruments by his contemporary French colleagues.

For the period from about 1730 to soon after the French Revolution of 1789, hundreds of tree-ring patterns from the soundboards of French instruments, many made in Paris, have been analysed and dated. It has been found that the vast majority correlated highly significantly with each other, but rarely with data from instruments made elsewhere. This strongly suggests a specific wood provenance that was seemingly only available to luthiers operating in France. While correlations with occasional instruments from outside France were also identified, the levels of statistical significance were always inferior to those achieved between French instruments.

It would appear that the wood used by Panormo while in Paris responded similarly to many soundboards found on instruments by his contemporary French colleagues

Although no reliable records exist as to the exact provenance of the wood predominantly used by 18th-century French luthiers, it may have been from the Massif des Vosges region. Exploitation of this location as a source of tonewood seems logical as it is the nearest mountainous area to the town of Mirecourt, the main instrument-making centre in France outside Paris. The highest peaks in the Vosges reach just over 1,400 metres above sea level and several coniferous species are native to these mountains. These include several varieties of spruce and pine trees.

The general appearance of many bellies from 18th-century French instruments and the specific morphology of their growth rings suggest that they were made from something other than Norway spruce (picea abies(L.)Karst), perhaps from the related Abies or Picea species. Despite this apparent diversity in species, French soundboards made from seemingly separate conifer species also correlate highly significantly with each other, suggesting that they were subject to very similar climatic and geophysical situations and therefore were probably grown in the same region. The species used by the 18th-century French luthier Louis Guersan and many of his contemporaries rarely display convincing features of Norway spruce. Equally, the soundboard of a viola attributed to and probably by Vincenzo Panormo (owned by the Royal Academy of Music in London), as well as other examples by this maker, in particular those made in Paris, appear to be made of wood from a species other than Norway spruce. The visual characteristics of these Panormo instruments fit rather better with the ones encountered more frequently on French instruments of the 18th century.

The high level of correlation found among data recovered from the majority of pre-Revolution French instruments raises interesting questions. The French guilds or corporations active during that period rigorously controlled many aspects of the life and work of artisans. It is likely that instrument makers were bound by obligations controlling the supply of timber and were not allowed to source their wood independently.

By 1779 Panormo had returned to Paris and was registered as a luthier in the ‘Communauté des Maîtres et Marchands Tabletiers, Luthiers, Éventaillistes de la ville, fauxbourgs & banlieue de Paris’ (see part 2 of Andrew Fairfax’s biography). He would undoubtedly have had to abide by the constraints of this corporation, and indeed as we have seen, our dendrochronological results suggest that he ended up using wood from the same accredited timber merchants who supplied other French makers. The corporations were finally abolished in 1791 and a radical and final shift in French tonewood provenance took place over the next decade.