Venice

In part 1 we saw how the cello evolved in the 16th–18th centuries through the cello makers of Cremona and Brescia. For the most part, theirs was a homegrown tradition where several generations of family members improved upon each others’ work. The proponents of the Cremona and Brescian schools also tended to be native citizens of those cities. The cello making traditions of many other parts of Italy, however, were built by outsiders. Many of the great cello makers of the Venetian and Roman schools came from the Tyrol or from the northern slopes of the Alps: Sellas, Kaiser, Goffriller, Tecchler and Platner were all relatively recent arrivals from the north. Even the great Venetian cello makers with Italian origins were foreigners in Venice: Montagnana, Tononi, Serafin, and Pietro Guarneri all came from elsewhere in Italy to ply their trade in the Serenissima Republic.

The great migration of skilled instrument makers to Italy and other parts of Europe in the late 17th century was largely the result of an excess of talent in the Bavarian instrument making city of Füssen. Situated in the foothills of the Alps, next to a limitless supply of excellent spruce, and along a key trade route linking northern Europe with Italy to the south and Vienna to the east, Füssen had developed into a bustling instrument making town by the Middle Ages. In 1562 the Füssen instrument makers organized into a guild – the first of its kind in Europe – and one of the restrictions was that the city would be limited to no more than 20 violin making workshops at any given time. [1] Naturally this led to the exodus of many talented makers and started the greatest labor migration in the history of violin making. Füssen makers went as far afield as Cremona, Vienna, Paris, Rome and Naples in search of employment, but perhaps the greatest city to benefit from the overabundance of Tyrolean talent was Venice.

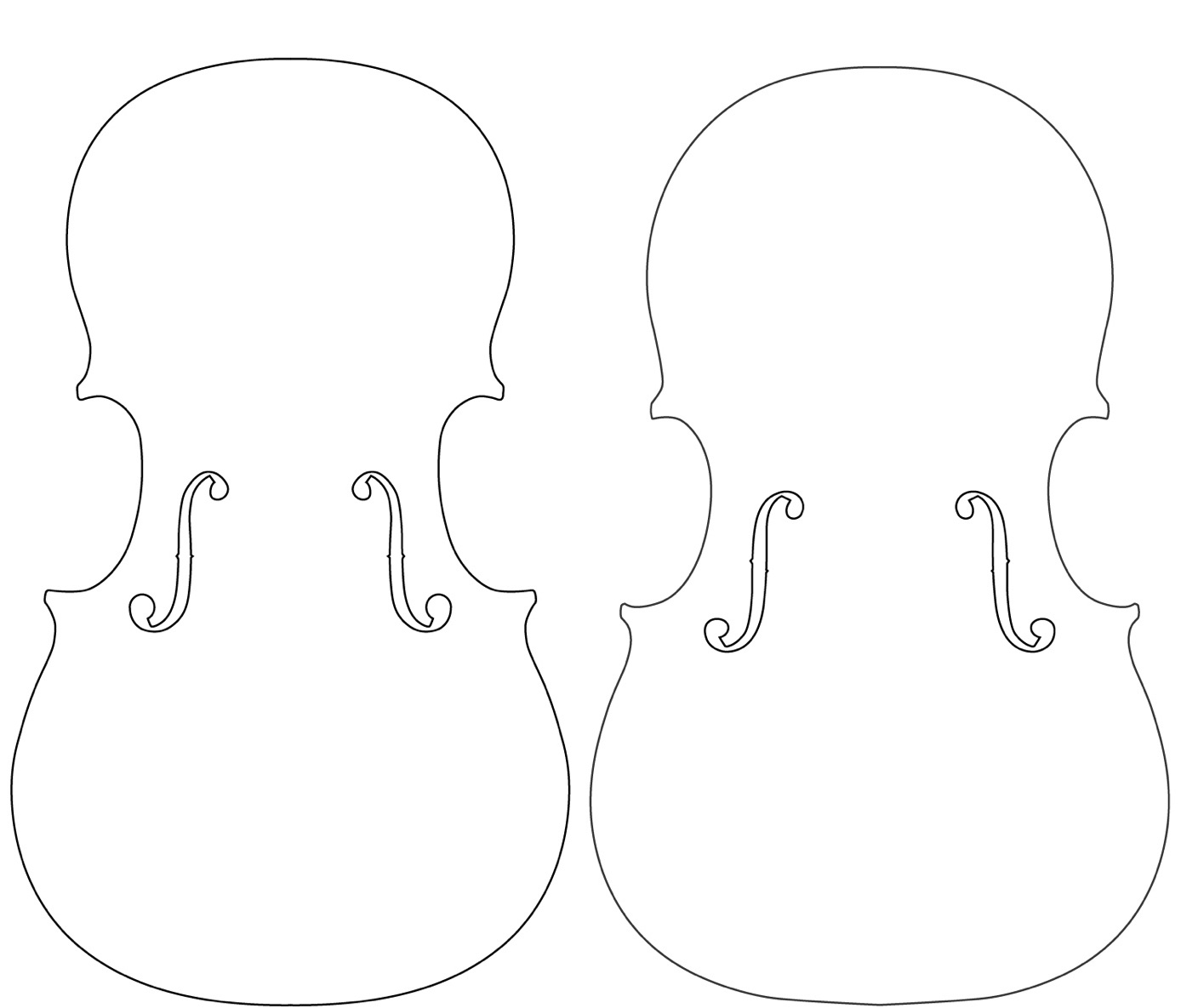

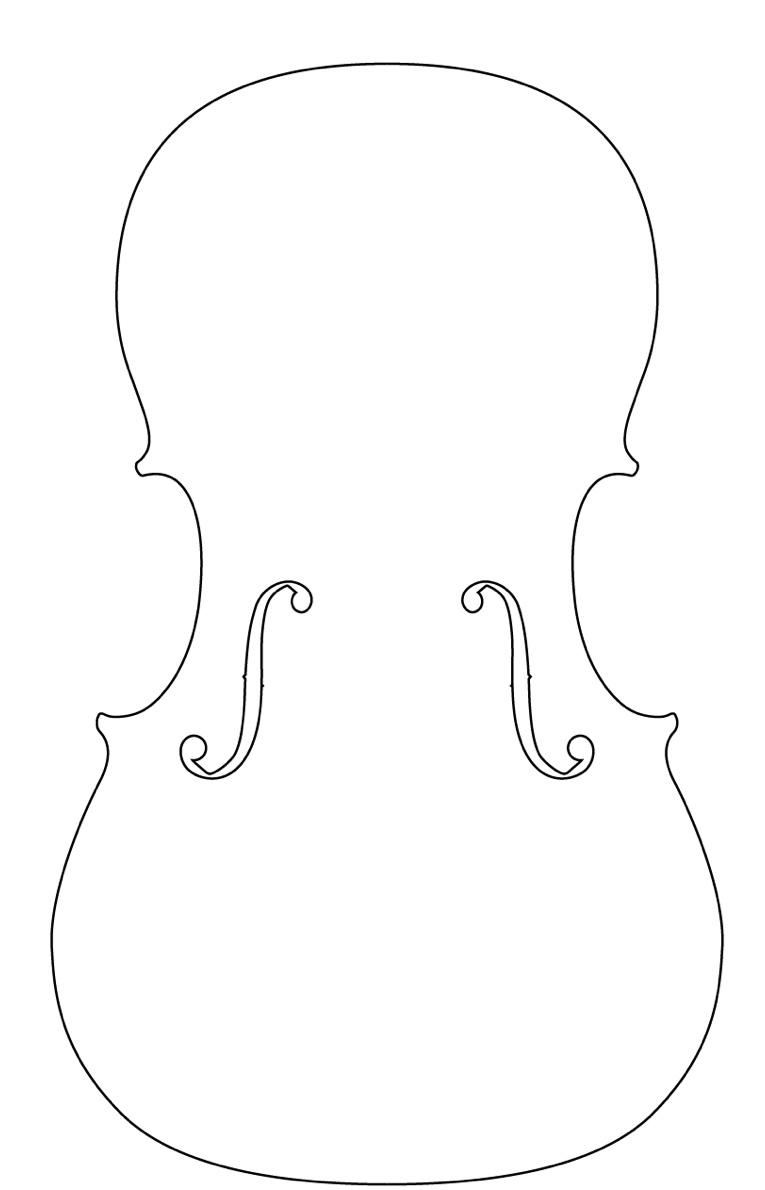

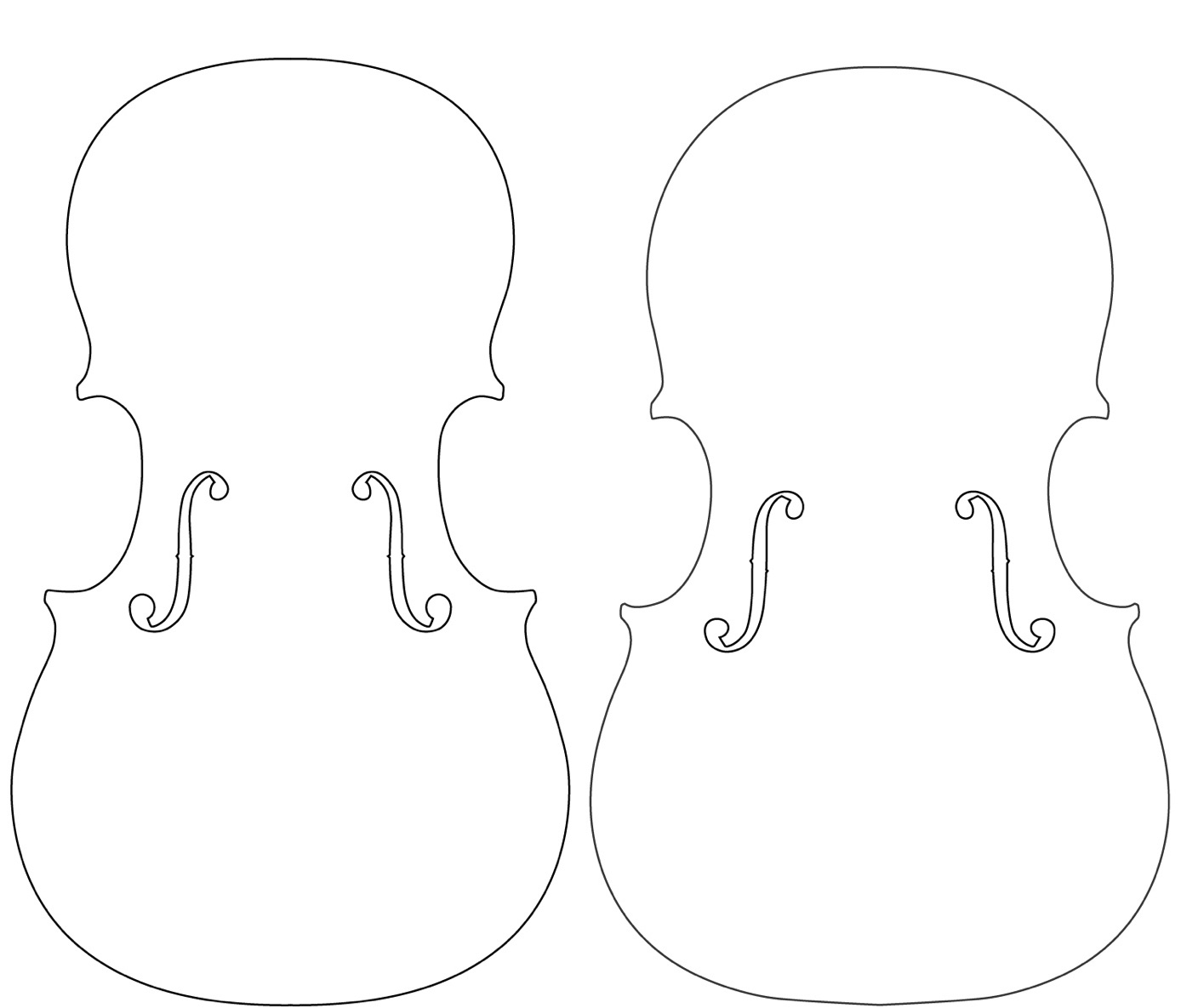

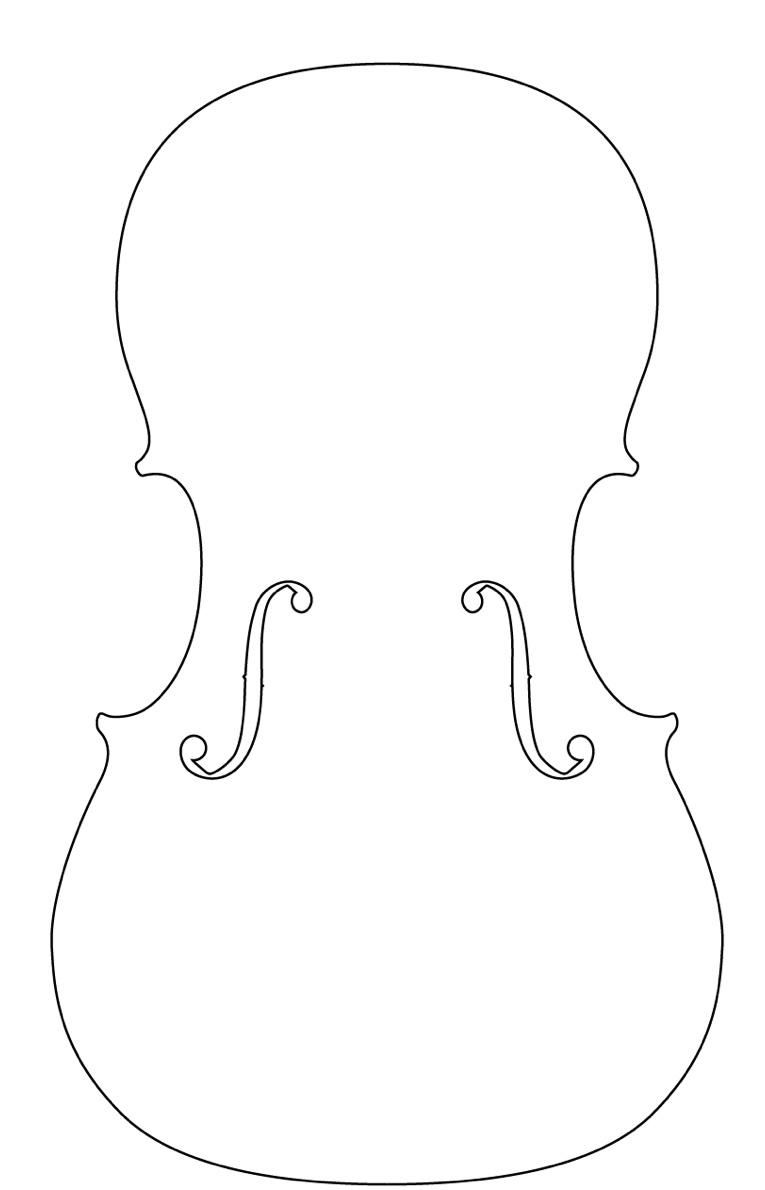

Patterns from Goffriller (left) and Montagnana

The first of the great Venetian cello makers was Matteo Goffriller (c. 1659–1742), who came from the town of Bressanone in the Tyrol to work for Matthias Kaiser. [2] Kaiser was primarily a builder of lutes and other plucked instruments but Goffriller seems to have specialized early on in making cellos. In fact of the instruments attributable to Gofriller the ratio of cellos to violins is approximately 2:3; with Stradivari, in contrast, the ratio is closer to 1:10. Goffriller’s cellos range from 70 cm small-sized cellos to larger 77 and 78 cm instruments most of which have since been reduced. The outlines of his cellos are highly variable, which together with variations in the shape and setting of the soundholes gives each instrument a unique appearance and personality. The heads of Goffriller cellos are easily identifiable: long and graceful with a round and slightly diminutive volute standing proud above a tapered pegbox. Goffriller’s varnish is perhaps his most outstanding contribution to Venetian cello making and set the standard for the makers that followed – a rich reddish-brown sauce applied thickly, which after time coagulated into an extremely textured and glorious craquel. Goffriller’s son Francesco succeeded him and made excellent although somewhat more rustic cellos but soon moved outside Venice to Udine.

Matteo Goffriller was the presumed teacher of the other great Venetian cello maker, Domenico Montagnana (1687–1750). As Stradivari and Guarneri are to violins, Goffriller and Montagnana are to cellos. Montagnana cellos are shorter in body-length than Goffrillers but they are considerably broader in the bouts and in the waist, making for a compact, maneuverable instrument with a highly resonant, full-bodied tone. The archings are rounded but modest and never exaggerated. The sound-holes are modelled on an Amati pattern and precisely executed. The maple and spruce are of the finest quality and covered in a glorious rich red-brown craqueled varnish.

Pietro Guarneri of Venice provided the first important intersection between Cremona and Venice

The Cremonese and Venetian violin making traditions have their first intersection when Pietro Guarneri (1695–1762), the son of Giuseppe Guarneri ‘filius Andreae’, came to Venice in around 1717. No doubt this made for some useful cultural exchange of working methods, tools and techniques. In fact it is only after Pietro’s arrival in Venice that we see the widespread usage of such iconic Cremonese techniques as the internal mold and the central pin. Pietro was a maker of exceptional cellos that perfectly fuse the best parts of the Venetian and Cremonese traditions. The workmanship is careful and controlled but graceful and expressive. The model is reminiscent of ‘filius Andreae’ but distinctly recognisable with its wide set sound-holes, attenuated stems and high-waisted C-bouts. The lavish maple and stunning deep-red varnish make them among the most noble of Venetian cellos. Altogether there are fewer than 15 surviving Pietro Guarneri cellos. These arguably represent the best cello work of the Guarneri family considering only a pair of cellos have survived from his brother, Giuseppe ‘del Gesù’, and his uncle, Pietro of Mantua.

Santo Serafin (1699–1776) arrived in Venice from Udine also in the year 1717. There are fewer than a dozen surviving cellos by Serafin and each is of exceptional quality and craftsmanship. His model shows the inspiration of Stainer in the outline and the head and Amati in the sound-holes, although the back length is a manageable 73–75 cm. The shallow C-bouts and short, pert corners create an effect of compact refinement and graceful elegance. The wood used for the back is invariably of the highest quality quarter-cut maple with a strong, deep figure that was burnished before being varnished so as to create a three-dimensional rippled effect to the touch.