In the 1960s the ‘Cannon’ was refitted and set up for modern playing conditions. From the late 1970s up to the first years of this century it then went through quite an intense period of use and some of the world’s best players had the privilege to play it. More recently this has been reduced and the ‘Cannon’ now enjoys a more retired life in the refurbished Sala Paganiniana in Genova’s Palazzo Tursi, under the supervision of the Museums of Strada Nuova. It was refitted in 2004 with copies of the fingerboard, pegs, bridge and tailpiece used by Paganini and is exhibited with a set of plain gut strings, as the great virtuoso would have played it.

The ‘Cannon’, shown here in its pre-2004 set-up, was donated to the City of Genova in 1851 and was rarely played for the next century. Photo: Peter Biddulph Ltd

More photosThe ‘Cannon’ has also recently undergone a non-invasive scientific project of monitoring in order to get as much information as possible about the elasticity and physical properties of the wood, and about the physical reaction of the violin while being played. The aim of this research is to monitor the static condition of the violin in order to reduce the risks of use. Luckily the whole construction of the ‘Cannon’, with its thick and structurally sound plates, still forms the most important conservation feature of the violin: this relationship between its bold structure and its powerful sound is an intriguing matter that is mysteriously difficult to investigate.

The ‘Cannon’ possesses a number of features that would seem to complicate its playability. The string length of the violin is 330 mm: long, but within the normal range. It also has a long stop length of 198 mm (the standard is 195 mm), yet the neck is slightly shorter at 128.5 mm than the modern standard of 130 mm and is thicker at the heel, which may create a sense of discomfort for modern players. The neck of the violin was extended from its original length of 125 mm and reset into the body with the use of nails. It is not known when this was done nor who commissioned it from whom, but this kind of work was common in northern Italy between the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

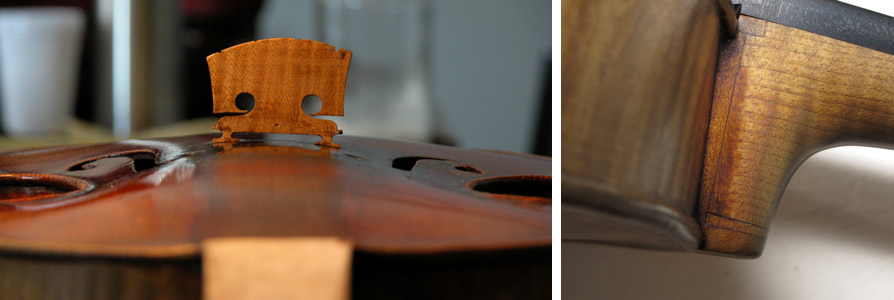

The tiny bridge possibly used by Paganini, shown on the belly of the ‘Cannon’ and (right) the neck root. Photos: Bruce Carlson, Photographic Archive, City of Genoa

It seems likely that Paganini used to move the bridge in order to adjust the string length to his needs: the marks on the wood in the bridge area are deep and wide and some scratches seem as though they were created by the fingernails of the user; adjusting the bridge position could have been quite easy with the old-fashioned bridge that came with the ‘Cannon’, which has short and narrow feet, allowing more room for movement. It is not known if this tiny bridge was used by Paganini but it certainly fits the ‘Cannon’ properly.

The freely carved head of the ‘Cannon’. Photos: Peter Biddulph Ltd

In this sense it seems that the neck projection of the violin, which is very low at 25.5 mm, was never significantly altered. The particular kind of neck-set nailed to the neck root and the uncut belly edge that is set directly on it, hold the neck firmly, avoiding any significant change in the projection; this low neck projection and the neck overhang determine a low angle on the bridge that enables the ‘Cannon’ to work with less pressure than a violin mounted with a modern neck set. This is an intriguing matter if we consider the ‘Cannon’s unconventionally thick plates and ribs, which give it a considerable weight of 434 grams (including fittings).

The extreme thickness of the back plate (6.2 mm at the highest point) was kept full by ‘del Gesù’ almost right up to the edge, while the thickness of the belly (3.4 mm in the center bout) seldom decreases below 3 mm. The concept of this structure is connected to that of the arching, which when compared with Guarneri’s earlier violins, appears to have been rethought and approached with care. In contrast with the more freely cut scroll, for instance, the archings look admirably executed; the curves are kept full and even right up to the edges, giving the ‘Cannon’ a broad appearance and an almost Brescian look. The heights of the plates are each 15 mm, the scoop is more hollow on the back and the height of the edges gives the impression of an extreme hollowness. These features give the ‘Cannon’ the impression of a large instrument, although its back length is actually only 353 mm. On the front this feeling is enhanced by the long stop of the soundholes, their different slants from the centerline and the fact that the bass soundhole is about 2 mm longer than the treble.

The sound of the ‘Cannon’

The question of what the ‘Cannon’ would sound like if played regularly has accompanied the violin for over a century, from Bronislaw Hubermann, who played it in 1908 for a few encores, to today’s top soloists. Playing a violin that usually lies silently in a glass case, de-tuned below concert pitch, is not easy. The reaction of the ‘Cannon’ can differ according to the player or other circumstances: usually its wake-up time is quite short; in other cases it seems to be more reluctant. Two players and the violin’s head conservator give their views below.

Bin Huang

Paganini Competition winner, 1994

I was thrilled to get my hands on Paganini’s own violin. But perhaps because of the brevity of the warm-up time and of the performance in 1994, I did not appreciate fully what it could offer until the second time I played it, in 1995. I played the Beethoven Violin Concerto in concert and even now I can still hear the hauntingly beautiful high notes on the E string and the dark and rich resonance on the lower strings. The timbre of the instrument is at once brilliant and sweet, powerful and refined, rich and light, dark and penetrating. At times I felt that it produced colors and nuances that I had never heard before. It offered inexhaustible possibilities for expression.

‘Even now I can still hear the hauntingly beautiful high notes on the E string and the dark and rich resonance on the lower strings’

When I played it for the third time in Tokyo in 2000 it took about half an hour to wake up, but then it produced the most gorgeous sound I have ever heard.

Peter Sheppard Skaerved

Viotti Lecturer at the Royal Academy of Music, London

I wanted to play the violin in its purest state, as it were, with gut strings and with no chin rest or shoulder rest. The experience of playing on the ‘Cannon’ on gut, with a copy of the Paganini bridge revealed that the violin works in registers. By this I mean that the zones of the violin – not just pitches, but also the hand zones on the instrument such as high on the G string, low on the D and A strings and so on – each have clearly defined colors and edges. This is much more marked than on a modern set up, where the registers are more homogenized.

‘I wanted to play the violin in its purest state, with gut strings and with no chin rest or shoulder rest’

With gut strings on, the violin still lives up to its name and I did not encounter any problems of balance playing with a modern chamber orchestra. This registral delineation is important because it reflects Paganini’s own music; it also matches the contemporaneous fortepianos, where the registers are equally clearly defined. I also found that the extreme colors in which Paganini specialized (such as sul ponticello and sul tasto) result in far more colorful, even ‘haunted’ spectra with the violin in this set up.

The ‘Cannon’ in the 19th century. Photo: Photographic Archive, City of Genoa

Bruce Carlson

Restorer and violin maker/conservator to the ‘Cannon’ since 2000

The ‘Cannon’ offers us a glimpse of how instruments must have appeared in the first decades of the 19th century when they were brought out of Italy. Conservation of a violin in such a rare state of preservation must necessarily be the primary goal, as instruments such as this yield invaluable information as an irreplaceable historic document.

‘Each player gets his or her own sound from the Cannon, some easily and some with difficulty’

Consensus regarding the sound of the ‘Cannon’ was very favorable when it was played by various soloists including Joshua Bell at the 1994 Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ Exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. This challenges the argument that a violin must be continually played or it will ‘lose its voice’. Each player gets his or her own sound from the ‘Cannon’, some more easily and some with difficulty, but the combination, even if for a brief recital, is always a very rare and special occasion.

Thanks to the Musei di Genova for kind permission to reproduce photographs of the ‘Cannon’.

Violin maker Alberto Giordano is assistant curator to the ‘Cannon’; his extensive research in the Genovese archives led to the refitting of the violin in 2004.