Stéphane Thomachot apprenticed under Bernard Ouchard in Mirecourt before establishing his own workshop in Paris in 1981. He earned gold medals at the 1982 and 1984 Violin Society of America competitions and later served on the jury of numerous international bow-making competitions. He is a prolific and highly sought-after maker who mentored many bowmakers of the next generation. Twenty years ago, Stéphane moved to Cucuron, about 60 km north of sunny Marseille.

I’ve been a fan of Stéphane’s work ever since my earliest days at Tarisio in New York: An American collector showed me the bows he owned and called Stéphane “the best French bowmaker today”. I was rather moved when Stéphane chose Tarisio for the sale of this special bow.

When I called him up to chat about the bow, he told me the light in Cucuron was particularly good that day so he wanted to take the opportunity to finish the bow he was working on. I spoke with him the next day, once the stick was finished and enjoying a tan in the UV lightbox.

Can you talk about your time in Mirecourt studying with Bernard Ouchard? Why did you decide to go there?

It goes back to ’75 — in two years it will be 50 years! That was the fifth class. There were four more I think.

I grew up in Jouy-en-Josas near Versailles, and I played the guitar, classical and not classical, and I always wanted to make one. It was a family friend named François Vercken, the director of France Musique at the time as well as a musician-composer, who told my parents that there was a school in Mirecourt that Etienne Vatelot, Jean Bauer and Bernard Millant had just opened. So I took the train to Mirecourt [now an abandoned railroad] in order to take the “Mirecourt tests.” This was at the end of June 1975. There were about 120 of us, and from the group they chose just eight: three for bow making and five for violin making.

The jury was made up of Bernard Ouchard, René Morizot, who was the violin making teacher, Marcel Deloget from Versailles, whom I had gone to meet before going, and maybe Jean Bauer, I can’t quite remember. I do remember that Marcel told me that I had to learn to draw a violin head, seen in three quarters. I had practiced a lot because I was bad at drawing, and I still am!

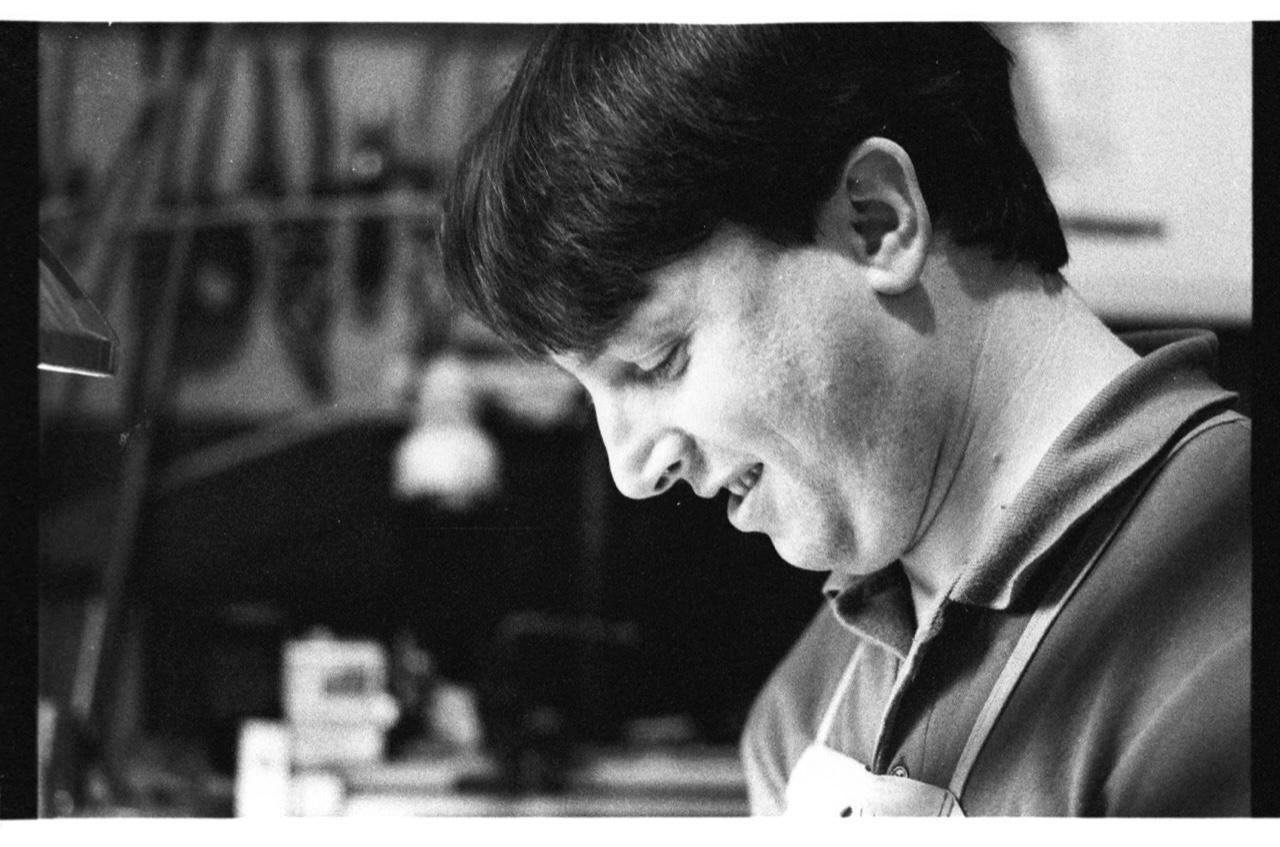

Stéphane Thomachot in Mirecourt, aged 18.

During the tests, we were given bows at different stages of making and you had to put them in order. It wasn’t complicated, but you had to understand the logic. At the end of the test I was offered bow making rather than violin making, and I said ok. I turned sixteen in July and started in September. I was in the class with Jean Grunberger and Pascal Lauxerrois.

Being a teenager in a small village in the Vosges where it’s cold and grey, it’s not always pleasant, but now of course, when you look back almost 50 years when you were young, it’s always good memories.

Bernard Ouchard in 1978 (photo by Stéphane Thomachot)

What do you think about current trends in bowmaking?

There are some bow makers who I really admire. In terms of style, the one who really makes me feel true emotions is Noel Burke, the Irishman.

There are some very beautiful things… but I classify bows into two categories, those I understand and those I don’t. I didn’t really understand style, even after school, because in Mirecourt we saw nothing. We had Bernard Ouchard’s models and we were supposed to make bows like him. I was among those who followed the French school, and the one that I began to understand a little bit and that spoke to me, it was from Voirin, Lamy too.

I was never a big fan of Sartory. I’ve never really understood that “belly” he makes between the first third and the second third of the stick. That said, these bows are very good to play in an orchestra. It’s surprising, but Sartory doesn’t have a great track record of soloists playing his bows.

A bow maker that can make me tear up is Eury.

But there is a real break in style with Voirin. All these big square heads that we had with the Peccattes, the Maires, the Henrys, the Pajeots, all that, and then Voirin started to make heads a little more elegant, which spoke to me. Though I do love the Peccatte and the Henry! A bow maker that can make me tear up is Eury. And Persoit too. I’m an absolute fan of Persoit now. But as a young bow maker, Voirin spoke to me. By the way, Henryk Szeryng played a Voirin all his life, it was his favorite bow.

The ex-Henryk Szeryng gold mounted Voirin, with a Vuillaume-style frog, recently sold by Tarisio Private Sale

So I was trying to make round heads and that went completely against the current. It’s true that from the 80s on, everybody started to make square heads, the frogs were more square, more angular and I wanted to stay in the roundness. But I admire a lot of those who make square heads too. Like Noel Burke for example. I also like Charles Espey, of course. And so many others.

I was a judge in the VSA competition in Los Angeles just last year. There was an hors-concours exhibition and I saw some bows by Morgan Anderson that are superb. I put him in the top five with Charles Espey. Another very nice bow was the one by Evan Orman (a very good bandoneonist by the way). He made a bow on a Vuillaume model, very well made, but the reason they don’t make Vuillaume frogs anymore is that the round hair is a little weird. I think that musicians prefer the attack of a very flat ribbon.

Actually, Vuillaume invented a lot of things in bow making, and there were some interesting things but nothing has stuck, whether it’s his style of frog, his self-rehairing bows…The steel bows, though, they were good and beautifully made — I would love to have one! I think they are very nice, and they hold their camber well over time. It’s amazing, they’re perfectly balanced to play and they work much better than carbon fiber.

A steel bow from the Vuillaume workshop sold by Tarisio NY in 2015

I had a friend and client named Jean Philippe Vasseur, a great guy, he was a principal viola in the opera, who bought a steel bow. It’s really an amazing work. Those who work with metal and see these today are amazed!

Let’s talk a bit about the gold-mounted bow in our current Berlin sale. How did you pick the wood?

I remember very well what the wood is. I bought it at an auction house, about fifty sticks that came from the Chardon workshop, and there were four or five really good ones, so this is one of those.

How would you judge the bow today?

Before I sent you the bow, I had to change the hair, which was thick and heavy. Now I know that doesn’t work, so I did a rehair like I do now. And I realized that it was missing a little bit of weight, so I changed the lapping. The one that was on before was lizard skin, so I put in imitation whalebone to be CITES compliant.

There is one thing that “disappointed me in a good way” as the Swiss say, and that is the work of the stick, seeing the facets of the octagon: I make them less well now. It’s incredible consistency, it’s super clean; I don’t mean to boast but I haven’t seen octagon sticks like that at the [last VSA] competition for example.

How many gold mounted bows have you made?

I must have made between 800 and 1000 bows but I don’t know exactly. Between 100 and 150 are gold mounted.

What did the VSA mean to bowmakers in the 80s?

It was the only competition for bowmakers at the time, and Charles Espey and I said, “Let’s do it.” We worked together in my workshop, which was at the time at 21 rue Custine, in Paris’ 18th arrondissement, and it was actually the first gold mounted bows Chuck and I ever made. By the way Charles also got a gold medal [in the 1982 competition], and Joseph Kun too – in the VSA journal, the photos of our respective bows are actually switched with one another! I really liked Joseph Kun. He was a Czech-Canadian émigré. He was very fond of machines; he planed his sticks by hand a bit, but his frogs were completely machine-made. And he had come up with incredible solutions, for example for his octagon eye ring. But today it would not be possible to enter these in a competition anymore, because using machines is against the rules.

How did the medal change your career?

It was after the 1982 medal that I really started to make new bows. There was a period of hesitation between ’82 and 84 when I was doing maybe three or four bows a year, and the medals made me want to continue.

I was also quite encouraged by Bernard Millant and Etienne Vatelot who told me my work was good and that I should enter bowmaking competitions. Before that, I did restoration for Vatelot and I used to show my work to Millant regularly. He was always very nice, very welcoming, at least with me. But it was Jean-François Raffin who worked at his place and did all the repairs and restoration.

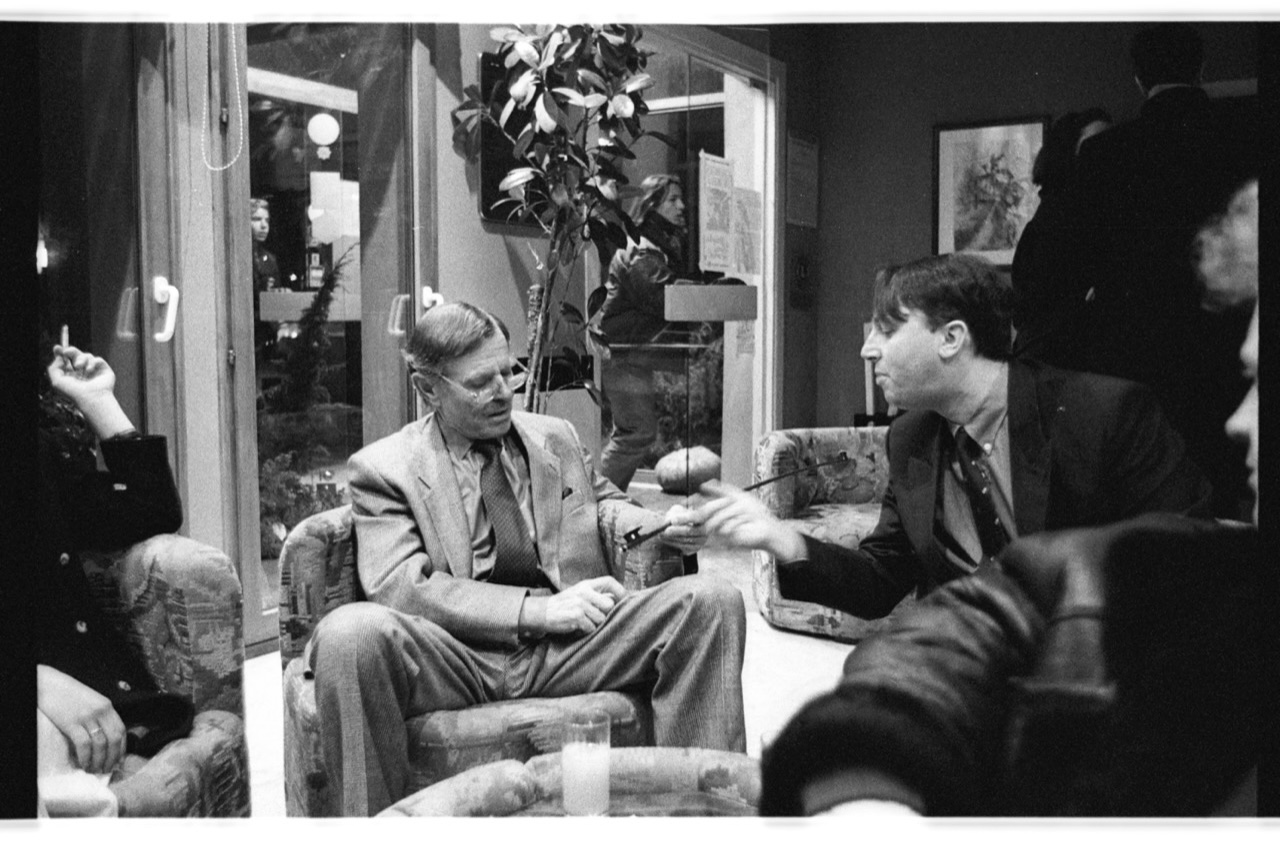

Stéphane Thomachot and Bernard Millant in the late 80s (photo by Marcus Wörtz)

I made important restorations for Vatelot. For example, Maurice Gendron’s Dominique Peccatte had a blown up button, and I made an identical copy of it. When I brought back the bow, Vatelot told me to keep the original button! I was also doing some repairs (hair, headplates, things like that) for Benoît Rolland.

I have good memories of Jacques Camurat, too, and Fifi, Philippe Dupuy. He was adorable, he was a very cultured person, and with a great sensitivity. Of course, he was the grandson of Eugène Sartory. Once, when I was young and stupid, I had an argument with him because I told him that I didn’t like Sartory’s way. Well, when you’re 20, anything goes.

In ‘84 I got another medal, and then I stopped competing. Since then, I’ve only made bows to order. Actually, I also won the Meilleur Ouvrier de France award in 1989. I came first in a competition of circumstances; there was the new Council of the crafts of art which had just been created at the Ministry of Culture, and I had received an application which I put aside and completely forgot. Then Vatelot called me and said, “Hey, didn’t you receive a dossier from the Minister of Culture? You have to fill it in quickly and send it, it’s important. I want a bow maker in the first promotion of maîtres d’art!”

I then judged the VSA competition once or twice. After that, since I had a workshop that was very open in Paris, I received a lot of trainees. There have been at least 50 of them, who have come from all over the world! And so I refused to be a judge for competitions for more than ten years, because I knew everyone who was competing, and I didn’t feel like judging the work of my colleagues whom I liked. After moving my workshop down south, I accepted their invitation [to be a judge] in 2010, and then again last year.

Are there distinct periods of your work?

I would say that there was the first period until 1988/90, when the bows had a little flavor of Mirecourt. In the 90s, I wanted to burn them all, and then I kept only the bow which you have in your sale, the one that won the 1982 VSA gold medal.

Stéphane Thomachot in the late 80s (photo by Marcus Wörtz)

And then the second period is when I was thirty years old in the 90s. When I see [those bows] again, I tell myself that I was going a bit fast. There was a year when I made 76 bows, a record year!

Then there are the bows that I started to make when I moved to the South of France in 2001. I’ve slowed down a lot in terms of quantity: I make one or two bows a month, and I take a lot more time to make them, they are more neat, a bit finer. I do about 20 a year.

Is there a meeting between one of your bows and a musician you particularly remember?

The first one who really made an impression on me was Shlomo Mintz, who was introduced by Amnon Weinstein, a violin maker of Tel-Aviv. In the late 80s, he was the director of the Israel Chamber Orchestra and he decided that everyone should play with my bows to create a sound identity. Unfortunately, it didn’t happen, but I would have liked it to have happened to see if there was really a difference in sound. But it is obvious that bows give sound to an orchestra. An anecdote that has nothing to do with it: my friend Yung Chin, with whom I am very close — we talk at least once a month on the phone, with Klaus Grunke too and Noel Burke — was telling me that he went to listen to the Berlin Philharmonic playing in New York, and he told me that the sound of the strings was mediocre, because practically 100% of the bowed string players came with carbon bows because of the CITES. We know that these bows don’t work, maybe they are very good in terms of dynamics, but not in terms of sound anyway.

I did quite a few quartets too. The first one was the Enesco Quartet. And then Peter Schidlof from the Amadeus Quartet, who played on the ‘MacDonald’ Strad viola (link to 40262). I think it was Vatelot who sent him to my workshop in ‘83 or ‘84. So I had him try the competition viola bow [in the current Berlin auction] — I only had this one on hand since I don’t keep any stock — and he thought it was great and ordered one. When he came to pick it up, he played the same evening with the Amadeus Quartet at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées. I went to listen to him.

I kept only the bow which you have in your sale, the one that won the 1982 VSA gold medal.

There was the Lindsay Quartet, one of the first British quartets. They commissioned two bow quartets from me, a first one in the early 90s, and a second one, five or six years later.

Otherwise there was Patrice Fontanarosa who often came to the workshop. There is a violinist who is really very faithful and adorable, that I know since she was about 18 years old: Sarah Nemtanu, who is the concertmaster of the Orchestre National de France. I met her at the Cordes-sur-Ciel festival. I was with my son Jules who was one or two years old, and Sarah said to us “Oh wait, I can watch Jules, he is so cute! Go enjoy the concert tonight and I’ll take care of him.” Then I made her a bow which she still plays today.

Why did you consign this bow to Tarisio?

I have a fondness for this bow, but I was always surprised by my colleagues who opened their bow box and had fifteen bows inside. I say that there are two kinds of bows: the bows that are for sale and the bows that are sold. And I prefer those that are sold. A good bow is a bow that sells!

Stéphane, last summer.

This award winning viola bow is lot 26 in our March 2023 Berlin auction.