Luigi Tarisio is an almost mythical figure in the history of the violin. His reputation as the ‘violin finder general’ or the sorcerer of violin collectors, offering ‘new violins for old’ in his search for forgotten masterpieces, has come to us through many writers of the 19th century. What we know is still very sketchy, but his historical position as the bridge between the close of the classical period of violin making in Italy and its subsequent revival and appreciation in the rest of Europe is certain.

Tarisio was born in about 1790 in Fontaneto d’Agogna, near Novara, 90 km north east of Turin, in the province of Piedmont. The violinist Giovanni Battista Viotti, who was also a noted violin trader, was born in 1755 in the similarly named Fontanetto Po, not far to the north east but not to be confused with Tarisio’s birthplace. Also in 1755 the violin collector Count Ignazio Alessandro Cozio di Salabue was born to the ducal family of Salabue, a village some 80 km east of Turin.

Views of the Romanesque Chiesa della Beata Vergine Assunta in Tarisio’s birthplace, Fontaneto d’Agogna

Cozio and Tarisio could not have been more different characters. Cozio was born into money and privilege, and was by some definitions a dilettante. Tarisio came from a poor working family and apprenticed as a carpenter. But the lives of both men are bound together by a passion for the violin. Cozio as a young man, disenchanted with a military career laid out for him, met the aged maker G.B. Guadagnini in Turin and became fascinated by the craft. Tarisio, on the other hand, is said to have taught himself the violin and began busking in taverns, traveling around his local area as an itinerant furniture repairer. The violin became his obsession and he began to realise that many old instruments he encountered on his travels were the work of great craftsmen, and of great intrinsic and artistic value. Whether he did offer new violins in exchange for these old masterpieces as he found them in homes, churches and monasteries as he made his way across Piedmont is really only speculative, but he was certainly an instinctive trader. Through studying the instruments he found, examining and comparing labels and styles, he developed that uncanny eye for quality that all antique dealers know and respect.

Tarisio eventually left his family in Fontaneto and is said to have found a modest apartment in an inn on Via Legnano, near Porta Tenaglia in Milan (although no archival records of this have yet been traced), which became his home and safe storage for the growing numbers of instruments he acquired.

Meanwhile Cozio di Salabue was very active in Milan; he worked in association with the Milanese makers Francesco and Carlo Mantegazza and stored much of his collection in that city, in the care of the banker Carlo Carli. The first inventory of his collection in Milan was written in 1801 and it was added to up until 1822. There is no sign of any interaction between Cozio and Tarisio (either at this point or earlier), but in the 1820s there must have been as great an accumulation of master instruments in Milan as has been seen in any one city. In that sense it was the capital of the violin trade, such as it was, before the later dominance of Paris and London. And it was in 1827, at the age of 37, that Tarisio took the bold step of traveling to Paris with six instruments from his collection: a Nicolò Amati, a Maggini, a Francesco Ruggeri, a Storioni and two Grancinos, to show to the dealer Jean-François Aldric at his shop in the rue de Bussy.

The Duomo in Milan. Both Tarisio and Count Cozio were active in the city in the early 19th century

George Hart, writing in 1875, [1] claims that Tarisio traveled the 500 miles to Paris by foot; not an unusual feat in the 19th century for the wandering laborers of Europe, and Tarisio himself seems to have alluded to the habit of making long journeys by foot more than once. He must have appeared travel worn after his journey from Milan. Aldric was not impressed and was able to beat him down on the price for his instruments, which he apparently carried in a sack. Two months later he returned to Paris, taking care to dress smartly and travel by coach, and visited all the main dealers in the city – Vuillaume, Chanot, Gand and Thibout – precipitating a bidding war between them and a more satisfactory result for himself. Thereafter he made annual visits to Paris, accumulating prestige and status with each appearance.

‘He was of common appearance – that he looked what he was, a peasant; he spoke French indifferently, dressed badly, and wore heavy rough shoes’

The Hills’ Stradivari book from 1902 records a description of Tarisio given by an instrument connoisseur of Brussels, a M. van der Hayden, who had known both Tarisio and Vuillaume: ‘He was of common appearance – that he looked what he was, a peasant; he spoke French indifferently, dressed badly, and wore heavy rough shoes. He was tall and thin, and had features of an ordinary Italian type. He used to relate that he walked to Spain when he went to that country to purchase the Stradivari cello.’ [2]

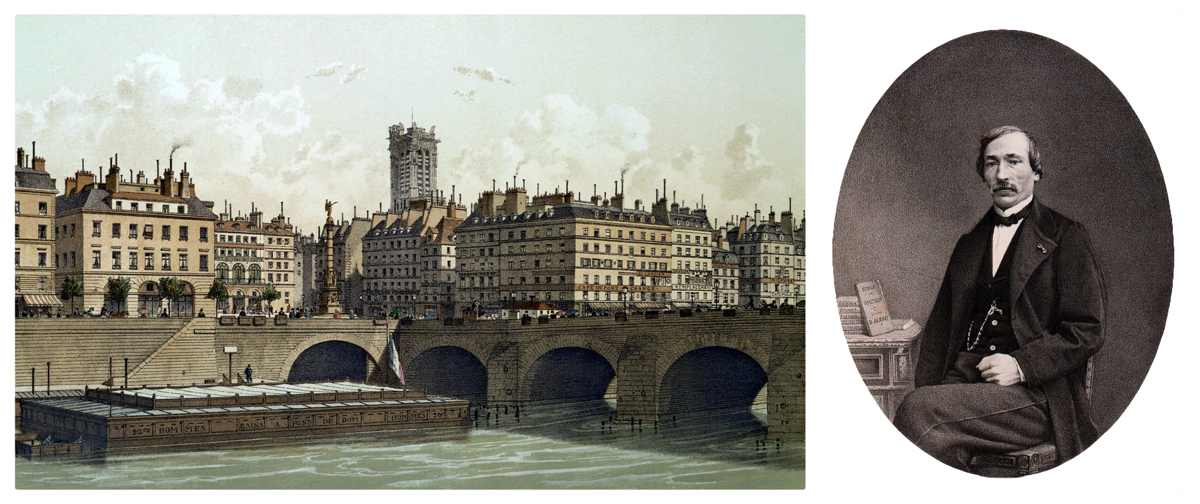

A lithograph of Paris in 1830, a few years after Tarisio’s first visit to the city; right: the violinist Delphin Alard, who is said to have quipped that Tarisio’s 1716 Stradivari was like ‘le Messie’

During that first visit in 1827 Tarisio announced that he had a Stradivari of 1716: ‘I have a Strad – so wonderful one must adore it on one’s knees!’ he said, according to the London dealer John Hart. [3] He refused to bring it to Paris, however, which led to J.B. Vuillaume’s son-in-law, the violinist Delphin Alard, commenting later that it was much talked of but never seen, like the Messiah (in French, ‘le Messie’). [4] Thus was named the world’s most celebrated violin, now resident in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. The actual year in which Tarisio purchased it from Cozio is disputed. It was probably in 1824, as recorded by Fétis, [5] although after his purchase of it Vuillaume wrote the date as 1827 in an inscription within the violin. This may have been the year Vuillaume first heard Tarisio mention it, and it was his mistaken interpretation that Tarisio himself had acquired it that year. Nevertheless, at some point the violin had passed from Cozio’s collection to Tarisio, and both he and the violin seem to have become the talk of Paris.

In part 2 John Dilworth looks at the impact of Luigi Tarisio on London’s literary society.

Notes

[1] George Hart, The Violin: Its Famous Makers and Their Imitators, London, 1875.

[2] W.H. Hill, A.F. Hill, A.E. Hill, Antonio Stradivari, his Life and Work, W.E. Hills, London, 1902, p.263.

[3] George Hart, Op. cit.

[4] Franz Farga, Violins and Violinists, Zurich 1940, English translation Rockliff Publishing 1950, p.97; W.E. Hill & Sons, The Salabue Stradivarius, monograph. London 1891, p.16. Also Vidal, Les Instruments a Archet, Paris 1876-78.

[5] François Joseph Fétis, Antoine Stradivari, luthier célèbre, 1856.

Additional sources

Roger Millant, J.B. Vuillaume Sa vie et son oeuvre, W.E. Hill, 1972.

Giovanni Accornero, Ivan Epicoco, Eraldo Guerci, Il Conte Cozio di Salabue: Liuteria e Collezionismo in Piemonte, Edizioni Il Salabue, 2005.

Christopher Reuning (ed), Carlo Bergonzi, A Cremonese Master Unveiled, Fondazione Antonio Stradivari, 2010.