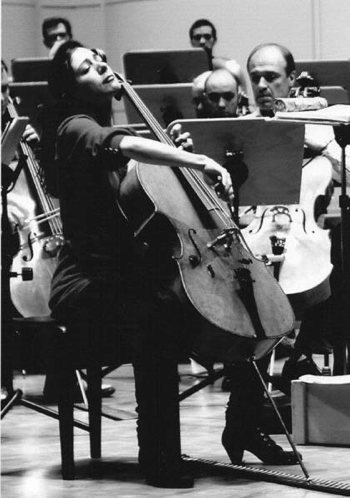

‘I love the sensuality of playing it,’ says Clein of her Guadagnini. Photo: Sussie Ahlburg

When Natalie Clein first met her cello, the 1777 ‘Simpson’ Guadagnini, it was respect at first sight – the love came later. She says, ‘It took me about two or three concerts before I realized exactly how much I loved it.’ She explains the difference between these two feelings: ‘I respect a lot of instruments because you can objectively see that they’re perfect. You play a D and you think it’s an amazing D, and then you play an F sharp and you can see how great that is. The love comes slowly for me, because you find your voice within the instrument. It’s a real relationship – you bring yourself to it. It’s a great companion that never lets me down, which I guess contributes to the love. We’re very well suited because I’m a physical person and a physical player, and I love the sensuality of playing it.’

She describes the instrument’s sound in visual terms: ‘I always think of it as a strong beam of light. I like the idea of this light being beamed across the stage into the hall. I’ve played Strads and Montagnanas and if you could see the sound wave for them it would be a rich puff of smoke, maybe, but with my Guadagnini the sound waves would be focused and beam-like. The sound has this rich, burnished gold quality.’ But it also has power: ‘It’s extremely even and it gives a good punch. I always think of it as a Ferrari – it’s got its 0 to 100 that really works for concerto playing.’

Clein has been consistent with her taste over the years. Until the age of 16, she played a Celoniato: ‘It wasn’t a million miles away from the Guadagnini, quite light in color. What I find amazing is that cellos sound how they look. I’ve always found that and I’m convinced it’s true. These instruments are both blonde, honey-like. A lot of Montagnanas are dark things with poplar backs and a dark, underground truffle feeling. The Guadagnini lives up in the branches.’ Her first main instrument was a Mittenwald cello, which she still has as a spare: ‘It’s very similar in size to the Guadagnini, by complete chance, and also a kind of light honey-color bronze, with a kind of sweetness.’

She remembers when she first switched on to the sound of good instruments. ‘I was 14, playing the Mittenwald, and it had been re-set-up by somebody in London. I went to play it and I was heartbroken because I felt that the sound had gone. My beloved cello didn’t sound the way I dreamed it would and I was really upset. During that visit they said, “Try this out”. It was the first time I’d put my hands on an Italian cello. I don’t know what it was – probably a Testore, a very good but not absolutely top Italian cello – but I remember realising there was a whole other world of sound and possibility here. It was so easy to play and to make a beautiful sound. That was the beginning of a really exciting search for a better cello.’

The ‘Simpson’ cello, made in Turin in 1777, is a late Guadagnini work

Choosing an instrument often involves compromise and Clein is clear about what she prioritizes: ‘When I was younger I would always play the top of an instrument first. I would never sacrifice an A string for a C string, and I might go the other way if I had to. If I had to choose, the A string is more important than the C string – I’m sure for a lot of cellists it’s the opposite.’ Other instruments may turn her head, she admits, but not for long: ‘I’ve have played a few cellos recently and fallen in love with the lower register, and I have missed it when I have gone back to my cello, but I wouldn’t swap anything. This is the cello of my life, and I can’t imagine wanting another.’

Clein is certainly monogamous with cellos. ‘I’m not one of these cello freaks who goes from cello to cello – I’m pretty loyal. I don’t enjoy the process of looking. I just want to find the right one. It’s fun to try other people’s cellos but in the end it’s your voice. It’s serious – it’s not a game or a hobby. There’s a wish to create a deep commitment and tie with something external to you but that is so intrinsically part of your voice.’

She owns only part of the Guadagnini, which sometimes makes attachment feel risky. ‘I hope I’ll be able to play it throughout my career – that’s my greatest wish – but I don’t think I’ll be able to buy the whole thing. It’s frightening to think your voice could be taken away from you or belong to someone else.’

Performing with the Dortmund Philharmonic under Nicholas Milton in November 2011

But she is also realistic about the balance of the relationship: ‘I remember Gidon Kremer saying that ultimately your voice is within your own imagination. Of course I’d find myself with something else if I had to. But we’re inextricably linked, and I get a thrill every time I take it out of the case, look at it and start playing.’

The instrument has a relatively flat top, as she explains: ‘Most cellos have a high arch, but this has almost zero arch. This seems to do something wonderful to the sound. It’s very loud under the ear and also from further away – it has this carrying quality. It’s extremely easy to play because it’s quite small. Guadagninis are famously shorter in the hand than nearly all other cellos.’

The instrument was made in Turin by Guadagnini in his final years, and Clein draws a comparison with two of the great composers: ‘I love it because it’s a late work, and in the way of late Brahms or late Beethoven, they don’t care any more about fancy edges. They want the substance of the thing to be told and they don’t have much time to tell it – you can see the gouge marks in the scroll, for example. It feels like it was made by a maker full of confidence, who knows what’s going to make a good cello. It must be one of the perfect Guadagninis.’

Clein recordings featuring the ‘Simpson’ Guadagnini

Saint-Saëns: Cello Concertos

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Andrew Manze, Hyperion Records CDA68002, listen to an excerpt

Bloch: Schelomo etc; Bruch: Kol Nidrei

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Ilan Volkov, Hyperion Records CDA67910

Formerly editor of The Strad magazine, Ariane Todes is now a freelance writer and editor.